‘Valentine’ by Wendy Cope For as long as I can remember, I have always enjoyed learning about less well known poetic forms. We can all remember coming across limericks, haikus and possibly clerihews at primary school and having a go at creating some of our own. However, there are some other forms out there with just as long and established a tradition which rarely get much of a look in. The triolet, for example, is a form that I have only discovered in recent years, even though it has been around since at least the 14th century and enjoyed a revival in the late 19th century thanks to poets such as Robert Bridges, Frances Cornford and Thomas Hardy. Wendy Cope’s ‘Valentine’ is one of the best known modern triolets, and I have used it successfully alongside other examples to get Year 7 children playing with the form. A triolet is made up of eight lines. It follows an ABaAabAB rhyme scheme, where capitals refer to identical (or near-identical) lines and small letters refer to rhyming lines. Therefore, lines 1, 4 and 7 are identical, as are lines 2 and 8. This also means that the first and final couplets are identical. The lines are often, but not always, written in iambic tetrameter, i.e. with four stresses on the even-numbered syllables. With ‘Valentine’ I start not by giving any information about its form, but by asking the children to discuss the poem in pairs and ask if they can spot anything interesting or unusual about it. They will always spot and comment on the repetition and the rhyme, but, without any point of comparison, they understandably do not see a specific pattern. I then show them the following two poems and ask them to continue discussing: ‘The Puzzled Game-Birds’ by Thomas Hardy They are not those who used to feed us When we were young—they cannot be - These shapes that now bereave and bleed us? They are not those who used to feed us, - For would they not fair terms concede us? - If hearts can house such treachery They are not those who used to feed us When we were young—they cannot be! ‘Triolet’ by Robert Bridges When first we met, we did not guess That Love would prove so hard a master; Of more than common friendliness When first we met we did not guess. Who could foretell the sore distress, This irretrievable disaster, When first we met? -- We did not guess That Love would prove so hard a master. Without any further guidance from me, they are able to come up with an accurate explanation of the triolet form incorporating all of the key features, along the lines of the more technical one given by me above. The satisfaction that comes from ‘cracking the code’ in this way is a real spur for the children in terms of making them want to get stuck in with trying it out for themselves. After all, if they have been able to work out in just a few minutes how a triolet works, the logical next step is to want to put it into practice. Teaching poetry writing in this way neatly sidesteps the age-old problem of coming up with ideas of what to write about and shifts the focus instead to the more technical question of how to go about it. For some children, such an approach can be highly liberating, especially if they can be provided with a literal scaffold upon which to build their writing, like this: I copy this colour-coded grid multiple times onto sheets of paper and let the children try out different lines, making sure that their yellow and blue lines match up. If computers are available, I provide the grid in its original digital spreadsheet format and they can work in a similar way, chopping and changing until they have two refrains that work well in their fixed, repeated positions. I ask them to keep going away and coming back to their ideas repeatedly over several days, even weeks, the beauty of this form being that once you know the pattern, you can just wait for inspiration to come and then the rest will usually fall into place fairly quickly. Here are three triolets produced by the children using this method: Bird Song I can hear them, hear their song. Why can I not answer? Do love birds fly free? For that I long. I can hear them, hear their song. In this cage? Is it true? I can sing along? No, I am the captured dancer. I can hear them, hear their song. Why can I not answer? Sophie, aged 12 Poppies Poppies used to be my favourite flower But now I’ve changed my mind For they grew at daddy’s darkest hour Poppies used to be my favourite flower Now their sweet smell has turned sour For them at the graveyard you will find Poppies used to be my favourite flower But now I’ve changed my mind. Anna, aged 12 Dreams They happen in your head Vivid, colourful and bright Repeating what you could have said They happen in your head You talk to people that are dead Then you wake with an explosion of light They happen in your head Vivid, colourful and bright Isabel, aged 12 I find it interesting that this simple form seems to provide children with quite a lot of fertile ground, in spite of traditionally being regarded as somewhat light and frivolous. Quite why this should be so, I am not too sure, but I would hazard a guess that the ‘serious’ poet might think that eight lines of which one is repeated three times and another is repeated twice gives insufficient elbow room in which to make much of a point. Children, by contrast, are used to being economical with the (written) word, regularly knocking off 500 word stories in forty minutes without blinking. As teachers, we are used to marking stories in which whole lifetimes are lived out in the space of two sides of A4, so the brevity of the triolet is unlikely to faze younger writers. See, for example, this comic gem which might not be wholly out of place amongst Hilaire Belloc’s ‘Cautionary Tales for Children’: Poor Little Wendy There’s a shark swimming in the water And poor little Wendy’s losing her balance Splash! I tried to save her, but it caught ‘er There’s a shark swimming in the water It’s an important lesson it’s taught ’er Even though Wendy had lots of talents There’s a shark swimming in the water And poor little Wendy’s losing her balance. Tom and Sam, aged 11

0 Comments

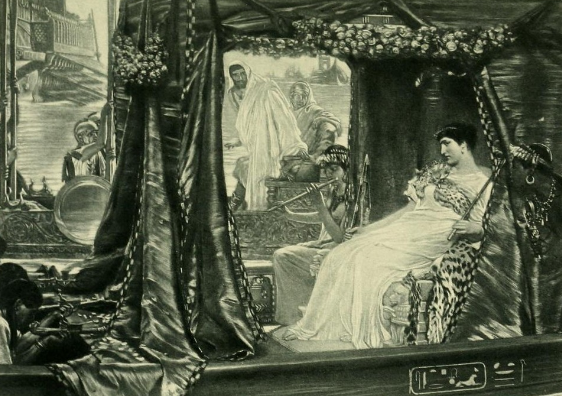

Enobarbus’ Speech from Act II, Scene 2 of ‘Antony and Cleopatra’ by William Shakespeare

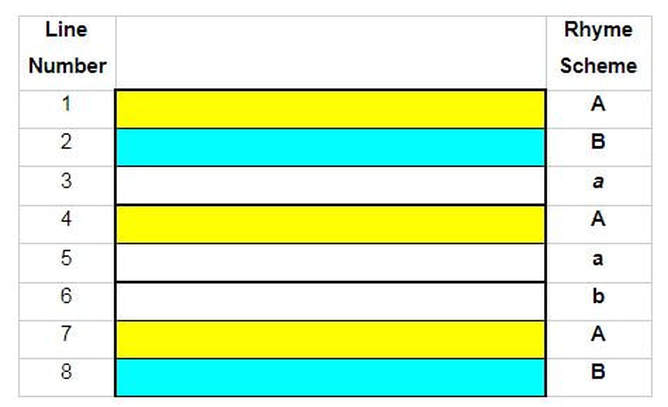

The barge she sat in, like a burnished throne, Burned on the water. The poop was beaten gold, Purple the sails, and so perfumèd that The winds were lovesick with them. The oars were silver, Which to the tune of flutes kept stroke, and made The water which they beat to follow faster, As amorous of their strokes. For her own person, It beggared all description: she did lie In her pavilion—cloth-of-gold, of tissue-- O’erpicturing that Venus where we see The fancy outwork nature. On each side her Stood pretty dimpled boys, like smiling Cupids, With divers-colored fans, whose wind did seem To glow the delicate cheeks which they did cool, And what they undid did. [...] Her gentlewomen, like the Nereides, So many mermaids, tended her i' the eyes, And made their bends adornings: at the helm A seeming mermaid steers: the silken tackle Swell with the touches of those flower-soft hands, That yarely frame the office. From the barge A strange invisible perfume hits the sense Of the adjacent wharfs. The city cast Her people out upon her; and Antony, Enthroned i' the market-place, did sit alone, Whistling to the air; which, but for vacancy, Had gone to gaze on Cleopatra too, And made a gap in nature. [...] Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale Her infinite variety: other women cloy The appetites they feed: but she makes hungry Where most she satisfies; for vilest things Become themselves in her: that the holy priests Bless her when she is riggish. When it comes to the question of teaching Shakespeare, there is an unspoken notion that certain plays will ‘work’ with younger children and others are best left for later: GCSE, A-Level and beyond. The ‘Witches’ Song’ from Macbeth, for example, is always an old favourite in the primary schools, alongside scenes from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Tempest and Twelfth Night. However, much as I myself enjoy these particular plays and using them as teaching material, I do not want to feel obliged to stick to tried and tested territory all the time. Overfamiliarity can spoil some of the magic of Shakespeare’s language. Who, after all, has not heard at some point heard children reciting ‘Double, double, toil and trouble...’ as if it were the ninth of ten ‘Hail Mary’s? I certainly remember being one of those children myself once upon a time, knowing the words but not really feeling anything as they came out of my mouth. Dipping into one of the less well known works, however, can yield some interesting results, particularly given that there is less likelihood that the children will have any previous contact with it, formed any preconceptions about it or absorbed it as if by osmosis. Whilst Antony and Cleopatra is a play that would typically not be studied until A-Level, it contains treasures such as Enobarbus’ description of Cleopatra, which can be looked at in isolation with younger children. The hyperbole of the imagery fascinates children, who revel in the idea of winds being ‘love-sick’ with perfume, the waters of the Nile being in love with the silver oars and particles of air wanting to pursue the queen, but for the impossible ‘gap in nature’ that this would cause. I use this speech as the stimulus for writing on the topic of incredible visions. The children are invited to think back to the most beautiful sight they can ever remember seeing and to jot down anything that springs to mind. They add to this any smells, sounds, tastes or textures that were experienced at the time. Finally, they are asked, on another sheet of paper, to imagine this experience being even better. What would be needed to make it even more special? I then leave it to the children to decide whether or not they want to experiment with iambic pentameter and to what extent they want to emulate Shakespearean language. Here are a few brief extracts taken from writing inspired by this activity: The Malvern Hills As I walked along the bare Malvern Hills. A single swallow swung down like a rope. The wind blew cold past my frozen ears, Burning a fiery chill of hopeless hope. Hills spread out before me like a painting. Each brush-stroke shaping wave after wave. The sleek curve fading away in the distance. The Malvern Hills under the sky’s great cave. David, aged 11 The Night Sky Her face sparkling with the glow of stars A billion glowing suns light up her face The sailors love her for she brings them home Even Orion and Sagittarius love her The mighty Scorpio doesn’t dare attack her For she is the mantle of his world... Hugo, aged 11 The Sea Your pebbles unroll like a never-ending story. Your story unravels like a crash of waves Becoming brighter than butterfly wings Than turning windmills and flickering fireflies. Auriel, aged 11 Sea Spray The waves roll across the beach like a page turning Scattering wistful, winding words across the sea. The letters spiral around my feet and spray across the burning sand Luring me to go into the world of words and water. Charlotte, aged 12 Bonfire Night The peaceful night is broken as a splash Of sunlight falls upon its black expanse A phoenix made from lava orb of fire The splashing multi coloured drops of light Some are showers of gold, some emerald green, Some red, some blue, some howling like banshees, The last are silent then shatter the night A lion roars, then fades in milky light The audience watch like statues in gasping awe At the magic they have all just seen As creatures cackle and crackle above their heads Oblivious to them as flames lap at sky Till it fades away and the the silence consumes the night Sam, aged 11 As can be seen in all of these extracts, children are adept at writing about ‘beauty’ in a more abstract way than we might otherwise expect. Rather than restrict themselves to the description of minutiae, they seize upon the opportunity to let their minds wander onto the mysteries of the universe. Their writing seems to ask the question ‘What is Beauty?’ and is content to explore it without trying to pin down definitive answers. To me, it reads as if they are forming a kind of dialogue with themselves through the medium of poetry, a dialogue which need not have a fixed beginning or end, but which can be revisited and reconsidered at any time. The very slowness of the act of writing poetry - whether it be slowed down by the form, by the content or by a combination of both - feeds deeper thinking and, in this sense, poetry and philosophy seem to go hand in hand, particularly where children are concerned. Where much of what they do in the classroom limits opportunities for deep thought and reflection, time being of the essence, poetry only really flourishes when it is allowed to develop at its own pace. As I write, all of the above examples are still very much works in progress, to which the children will, I hope, return at leisure over the coming term, next year and maybe even beyond. There are no deadlines, specific learning targets or boxes to tick. This is writing for the sake of writing and, whether it be in the context of discovering Shakespeare or any other great writer, the results speak for themselves. ‘Sonnet 18’ by William Shakespeare

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate: Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May, And summer’s lease hath all too short a date; Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines, And often is his gold complexion dimm'd; And every fair from fair sometime declines, By chance or nature’s changing course untrimm'd; But thy eternal summer shall not fade, Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st; Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade, When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st: So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee. I don’t remember exactly when I first heard the words ‘sonnet’ or ‘iambic pentameter’ for the first time, but I do know that it wasn’t until I was well into my secondary education. This is not to condemn any of the teaching that I received, which was, from my memory, filled with joy and fascination at every turn. Indeed, Shakespeare’s ‘Sonnet 18’ is one that I vividly recall encountering in one of my Year 7 English lessons. It was presented to us by reference to its first line - ‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?’ - as is customary and I remember the teacher taking us through, line by line, and asking us to take turns at ‘translating’ as we went. I got the third line - ‘Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May’ - and ummed and aahed my way to a rough approximation of Shakespeare’s meaning, thankfully realising that it couldn’t be anything to do with a tornado cutting a swathe through that farm in Kent owned by that bloke who plays Del Boy out of ‘Only Fools and Horses’, even if that was the first image that popped into my mind. This would be my first moment of realisation as to the ubiquity of Shakespeare’s language in contemporary English and I will always be thankful for this one lesson for tuning me into the universal relevance of Shakespeare. He is indeed everywhere: a living, breathing presence embedded ‘in eternal lines’ within the English language, the sentiment of this very sonnet standing as a prophetic epitaph to his own mortality. Looking back at the pleasure I took from ‘working out’ Shakespeare’s metaphors and discussing his rhymes in this lesson, I can’t quite decide how I feel about not being told anything about the form. Perhaps the lesson wasn’t long enough and we just didn’t get round to it. Perhaps my teacher just thought we didn’t ‘need’ to know about any of that yet. And maybe we didn’t, not in regard to what was going to come up in the Year 7 exam, at least. What I do remember, though, is that when I did eventually - two, maybe three years later - discover what a sonnet is and how iambic pentameter works, I felt like I had somehow missed out in the meantime. Satisfying as it was to have that epiphany - “Oh, right! ‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day’ is a sonnet!” - my underlying feeling was one of: “Why couldn’t I have been told that then?” In my experience of teaching, children respond best to poetry when they are given as full a picture as possible. Teaching poetry with regard only to meaning - but ignoring form as something of lesser importance or as something for ‘another time’ - is a missed opportunity. Where meaning can be elusive and arbitrary to the point of frustration for any and all of us - who hasn’t read a poem and thought: “What on earth is she on about?!” - form, where it is used, has rules which are objectively comprehensible and which can, therefore, provide a scaffold for understanding. Grasp the form and you have a starting point from which to proceed with the trickier task of interpretation. Better still, you have structure upon which to hang your own creative words. As Stephen Fry puts it in ‘The Ode Less Travelled’: ‘Learning metre and form and other such techniques is the equivalent of understanding culinary ingredients, how they are grown, how they are prepared, how they taste, how they combine [...] (W)e should never forget that poetry, like cooking, derives from love, an absolute love for the particularity and grain of ingredients - in our case, words.’ Fry’s comparison of poetry to cookery is particularly apposite in this age of the BBC’s ‘Great British Bake-Off’. Consider for a moment which contestants make it through to the latter stages. Is it the avant-garde experimentalists who ignore the rigour of the recipe book and use their baking as a means of ‘self-expression’, chucking in whatever comes to hand and just seeing what happens? Or is it the grafters who have practised, practised and practised again, developing a full grasp of the science behind the art? As far as cookery is concerned, I sadly fall into the former camp. (Thankfully, I am wise enough not to audition for the Bake-Off, although, were I to do so, it might provide a week of inevitable hilarity.) As for poetry, even if I am rather too lazy and lacking in inspiration to be the equivalent of a Bake-Off finalist, I certainly believe in the need for hard graft and this is what I seek to pass on to the children whom I teach. All of this is something of a roundabout way of saying that, in my opinion, teachers should not be shy of asking children to experiment with forms that have traditionally been regarded as being for ‘older’ learners. The notion that primary school children should be limited to ‘simpler’ short forms such as haikus and limericks ignores the fact that, arguably, such forms can be considered harder to reproduce successfully than supposedly trickier ones like the sonnet. Short is not necessarily simple. What’s more, being given an introduction to the form of the sonnet - its fourteen lines divided into octet and sestet (Petrarchan) or three quatrains and a couplet (Shakespearean); its rhyme and metre - does not necessitate the need for children to then write full sonnets in response. Valuable time can be spent using a poem such as ‘Sonnet 18’ merely as a model for single lines of iambic pentameter, couplets or poems in blank verse. Whilst I always spend a little time explaining the rules of strict iambic pentameter, whereby the strong beats should fall on the even-numbered syllables, I also make sure that we explore Shakespeare’s own lines to find examples of his breaking the rules. The children are quick to spot these variations, particularly if we directly compare a purely iambic line such as - And summer's lease hath all too short a date - with the more ambiguous scansion of - Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow'st - which arguably works better if rendered as follows: Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow'st To take another example, we might chat for a while about which of the following we prefer: Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade The different shades of meaning afforded by varying the stress are easily conveyed through repeated reading aloud, both by the teacher and the children, who themselves will often spot a new way of placing the stress to create yet another possible meaning. As Fred Sedgwick has noted: ‘It is certainly more effective to teach this [iambic pentameter] by saying the Shakespeare lines aloud with feeling and sensitivity to the meaning several times, thus allowing the iambic beat to sink into the brain, than to count drably: “te-tum te-tum te-tum te-tum te-tum”.’ With this particular example, I have found few children who favour the first properly iambic rendering, almost all of them preferring, together with Shakespeare, to ‘break the rules’ and tune into more natural speech rhythms. Thus, when getting down to the task of writing, whilst they might initially enjoy the simplicity of putting their strong beats in all the right places, tapping out their ‘te-tum te-tum te-tum te-tum te-tum’ with fingers on the desk as they go, it is never long before they gain in confidence enough to throw off the shackles and let the metre go where it chooses, as seen in these extracts: The Sun The sun setting over the luscious plains, Green as a grasshopper’s delicate wing... Alex, aged 13 Bird The gentle bird, peeking into the room, Wishing for itself, longs for that beauty Which he cannot have, and can only view, But for a moment, he can imagine. Patrick, aged 12 When reading back children’s attempts to ‘write like Shakespeare’, I am always struck by their chance discoveries of other metrical feet, without ever having them explained in advance. The dactyl (‘TUM-te-te’), for example, often crops up, as in these lines: ‘Green as a grasshopper’s delicate wing…’ ‘Cover the garden you planted with me’ When I spot these, I will always pause to comment on them and invite discussion from the class. I might compare them with other lines from other writers that spring to mind which echo their discovery, for example: ‘Woman much missed, how you call to me, call to me’ (‘The Voice’ by Thomas Hardy) Sometimes, the child whose line is rendered in dactyls like these will worry that this means that they have ‘gone wrong’ because there are only four strong beats, not five. This will then lead us into further discussion of Shakespeare himself and whether or not he worried about always having his iambs in a row. We might, for example, take the first line of Sonnet 18 and ask whether we really think that it sounds best with five distinct strong beats - Shall I compare thee to a summer's day? Shall I compare thee to a summer's day? Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day? Metrical purists would, of course, have strong opinions on this question and, being no expert myself, I have no doubt that I have already committed a dreadful faux-pas in even venturing onto this hallowed territory. However, where teaching children to write poetry is concerned, to my mind, we do not want to pass on the message that metre and form are straitjackets from which the writer should not even try to struggle free. Rather, in the school context at least, they are useful tools with which to model ways of writing in verse that are easy and fun to ‘get into’ and which tune the writer’s brain into the possibility and necessity of reading aloud, revisiting, redrafting and, above all, experimenting. Given the freedom to enter into a proper dialogue with Shakespeare, and to regard what can seem at first to be ‘rules’ as merely helpful guidelines, children are capable of rising to the challenge and using Shakespeare as a means to expressing their own ideas: Sonnet Shall I compare life to a fleeting dream? They both become changeless memories Although in the past you can change their stream From peaceful joy to fear and tragedy The path is decided by you, you alone Anything, everything could happen to you Life could be a battle you face on your own Or are we being controlled, if so by whom Somehow somewhere they must come to an end Like trees starved of sunlight with falling leaves Or a shattered plate you cannot mend They are so similar it’s hard to believe Shall I compare life to a fleeting dream? Blankets of time with delicate seams. Amy, aged 12 ‘Don’t Cry, Darling, It’s Blood All Right’ by Ogden Nash

By way of experimentation, I decided to use another Ogden Nash poem the following day with a group of gifted and talented Year 8 pupils. It is easy to slip into the mindset that playing with rhyme is more of an activity for the ‘little ones’ and that, by the time young people’s literacy and range of vocabulary is getting on for adult level, poetry writing time is spent more productively on, say, developing original metaphors. I am certainly guilty of such assumptions and I often think twice about using poems where rhyme is the stand-out feature, for fear that it will block the writer’s way to expressing what they truly wish to convey. However, give them a poem that uses rhyme in a way that they are unlikely to have encountered before and children are instantly intrigued and keen to delve in. They willingly abandon the misconception that the priority of their writing is that it must ‘mean’ something and instead, as the 4-year-olds did above, let the rhyme shape the narrative. The beauty of using a poet like Nash for rhyme experiments lies not only in his ubiquitous use of rhyming couplets, in which invented words and deliberately ‘wrenched’ rhymes, for example ‘porpoises/corpoises’, are used for comic effect. There is also the equally intentional disregard for metre: as soon as he reaches the word that makes his line rhyme with its predecessor, that is where the line ends, no matter how long or short it is. I chose ‘Don’t Cry Darling, It’s Blood All Right’ to introduce to my Year 8s because I thought that the theme would be something that they would identify with, but open any anthology of Nash’s poetry and you will find that pretty much any his works can be used to inspire a fun rhyming activity. Simply removing the final words from each line and doing a drag and drop activity on the interactive whiteboard is how we got going, reciting each line as we went and then calling out suggestions for the missing word. Such is the narrative clarity of Nash’s poetry, that the missing word seems to just spring into the listener’s mind automatically. Here is another couplet of his, this time from ‘The Adventures of Isabel’: “She showed no rage and she showed no rancor, But she turned the witch into milk and _______.” The fact that the missing ‘word’ is in fact two words (‘drank her’) makes the guessing no less simple. Do the same activity with a couplet like this one from ‘I Do, I Will, I Have’ - “Moreover, just as I am unsure of the difference between flora and fauna and flotsam and jetsam, I am quite sure that marriage is the alliance of two people one of whom never remembers birthdays and the other never _________.”

I asked the children what they thought of Nash’s varied line lengths. What did they contribute, if anything, to their enjoyment of the poem? Comments were made to the effect that the ‘wordiness’ made the poem seem more ‘chatty’, that it made the poet seem more ‘real’ to them, because they could tell what he thought about his subject matter. It felt like he was talking to his audience in person and they could get a sense of his humorous and ironic personality. The children also liked the way that his lines seemed to ‘break the rules’, that they hadn’t realised that you could do this kind of thing. This, I found particularly interesting. Somehow, my pupils have developed a sense that poetry has ‘rules’ that must be adhered to, even though they have come across poems of all kinds, written in both fixed forms and free verse. Upon what they supposed the ‘rules’ to be, they could not agree, of course, but something about Ogden Nash’s writing had given them a new sense of the freedom that the poet has to shun what he feels he ought to write and to focus instead upon what and how he wants to write. To give the children an idea of how to get going, I modelled a couplet that came off the top of my head as I wrote it out: “If you ever discover that you’ve lost your pet ostrich, Don’t dismiss the possibility that it’s been kidnapped and taken hostrich (hostage)” Already, as with the animal poems done previously with the 4-year-olds, a narrative has been seeded from the very constraints of the rhyme and it is not hard to imagine how this poem might be continued in the style of one of Nash’s own weird and wonderful tales. All the children needed now was a free rein to share ideas for rhymes out loud and access to an online rhyming dictionary. Within half an hour, they were coming up with their own homages to Nash, like this one, in which Hugo explores his personal fascination with impossibly long words: The Anathema of a Hippopotamonstrosaquippedaliphobic It is necessary to be incredibly stoic, Especially when one is hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliopho’ic, You must be careful when on the telephone, For fear of hearing ‘oxyphenbutazone’, You would much rather end up in a scarier prison Than saying antidisestablishmentarianism, You would certainly love to have itchy nosis If the alternative was suffering from pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis, But this is actually pointless because virtually no one suffers from hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia, So you should probably just ignore it until hell freezes ovia Hugo (aged 13) I enjoyed observing the way in which Hugo systematically worked his way through this poem. He knew that he wanted to find a rhyme for ‘hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobic’ as his starting point and quickly discovered that seemingly his only option that avoided repeating the ‘-phobic’ ending was ‘aerobic’, which didn’t seem to help too much. Undeterred, he experimented with Nash-inspired misspellings - ‘-phobbic’, ‘-phopic’ etc. - before having a go at removing letters. His ‘-pho’ic’ suddenly struck a chord and he immediately had ‘stoic’ in hand to play with and to drive his opening couplet. It was then simply a case of working through the likes of ‘oxyphenbutzone’, ‘antidisestablishmentarianism’ and ‘pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis’ to find suitable rhymes. Wanting to bring the poem full circle with a reappearance of ‘hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia’, he set to mindmapping such promising inventions as ‘globier’, ‘noblier’, ‘robier’ and ‘lobe-ear’ before thinking slightly further outside the box and coming up with the inspired ‘(hell freezes) ovia’, aping Nash’s deliberate misspellings in style. Needless to say, Hugo’s poem, along with several others, way surpassed my expectations at the start of the lesson, which I had envisaged merely as a bit of light relief following a typically joyless examination period, a chance to play with the linguistic Lego bricks before dipping back into the curriculum. If anything, it goes to show that, with poetry at least, when the challenge is there but the pressure is off, children can rise to the occasion and produce more lively and exciting poetry than they might otherwise do in more of a ‘formal’ lesson context. |

AuthorSixteen years of teaching poetry to children have furnished me with a wealth of ideas. Do dip in and adapt any of these for your own lessons. Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed