|

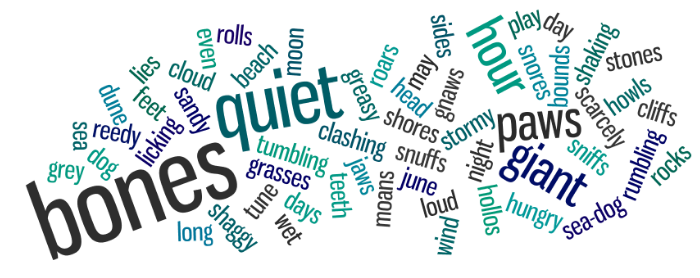

A winter weekend in Norfolk put me in mind of 'The Sea' by James Reeves. This is one of my favourite poems with which to teach extended metaphors. Read it, then watch the clip to see the simple power of the imagery, how wonderfully apposite and atmospheric it is... Had to fish out this section from my yet-to-be-edited poetry teaching memoirs. Definitely a poem to return to in the classroom again and again... The simplicity of James Reeves’ opening line of ‘The Sea’ is what makes this a particularly useful poem for teaching children about the power of metaphor. The poem almost seems to write itself after this basic premise, with the young reader’s mind already primed and excited to embark on the journey aboard Reeves’ train of thought. Indeed, this is one of the many poems that I have used with which the first 15 minutes of the lesson are often happily and productively spent bouncing around the implications of this initial line: Do you agree? Why? Why not? In what way is the sea a ‘hungry dog’? What does it do? Why does it do it? etc. The questions arise quite naturally and the children - whatever their age - always respond with plenty of creative and original ideas, prior to ever seeing anything other than Reeves’ opening line. Perhaps this comes down in part to its vocabulary, which is accessible to all and therefore linguistically unthreatening. I would argue, however, that the primary reason why this opening line hooks the young poet is that there is an innate openness to metaphor in most, if not all, children. The very use of the metaphorical ‘is’ as opposed to the simile-generating structure ‘is like’ immediately challenges the child to think more deeply and, in doing so, they are quick to tap into the noises, smells, colours and shapes of the sea that make the dog comparison resonate. When they then look at Reeves’ actual lines, children are quick to notice the long, low sounds of the sea echoed in the long vowel sounds - ‘rolls’, ‘hour upon hour’, ‘howls’ - and the irregular but insistent rhyme scheme - ‘bones/stones/moans’, ‘jaws/gnaws/paws/roars/shores/snores, ‘sniffs/cliffs’ - that evokes the varying rhythms of the waves. Assonance, alliteration and onomatopoeia play central roles in conveying the sounds of the sea in this poem and valuable time can be spent not merely in identifying where these are within the poem but what exact effects they are creating. I recall one Year 5 child mentioning that the lines - “And 'Bones, bones, bones, bones! ' The giant sea-dog moans” - enabled him not only to hear the sound, but also to see the long, white, rounded shape of the waves breaking on the beach. This multi-sensory engagement with metaphor appears to come quite naturally particularly to younger children, who are not hampered by the tendency to overanalyze and to doubt the validity their own instinctual responses. Thus, when given the freedom to explore any nature/animal metaphor, choosing either to follow the structure of ‘The Sea’ fairly closely or to take things in their own particular direction, children produce some truly fresh and memorable poetry: The Forest The forest is a lonely cow Lumbering and brown. She swishes, swishes the sky all night. With her smooth teeth and slow jaws Hour upon hour she chews The echoing, dark trees, And lows, lows, lows, lows! The lumbering forest-cow lows, Standing stock still On her huge tree-trunk legs. And when the morning wind is hollow And the sun sways in the windy day, She stays on his feet and rustles and chews, Shaking her fleas, wanting peace, She groans and moans long and slow. Ingo, aged 10 Much of what makes ‘The Sea’ such a memorable poem comes down to the clever use of repetition and rhyme, so as to provide a constant reminder of the recurrent sounds of the seascape. As Ingo has done in his forest poem, finding ways of conveying the sounds of a place through combinations of onomatopoeia, alliteration and assonance (‘swishes, swishes the sky all night’/’lows, lows, lows, lows’/’She groans and moans long and slow’) really appeals to the child’s innate fascination with words as playthings to be put together rather like Lego bricks to create colourful, crazy structures, as opposed to using them simply to string together units of meaning. Like Reeves, Ingo has ‘built’ his forest metaphor from a montage of interesting sounds and images, allowing him not to get bogged down with literal interpretation. To further facilitate children with tapping into this technique, a very useful app to consider using is www.wordle.net. Insert any text into it and you can instantly create a ‘word cloud’ of it, in which the more often a word occurs, the larger it will appear. Here is a word cloud of ‘The Sea’ with common words (e.g. ‘the’, ‘and’, ‘but’) removed: Word clouds such as these can be used to introduce a poem, in this case, for example, by asking the children to make suggestions as to what the poem represented by it might be about. The prominence of ‘bones’ and ‘paws’ might well lead the children to identify the dog theme fairly quickly; those who then look more closely to find ‘cliffs’, ‘sandy’ and ‘beach’, for example, will start to ask themselves questions. Is this a poem about a dog running around on a beach, maybe? Already, the images of ‘dog’ and ‘sea’ will be brought together in the child’s mind and everyone can set to work on spotting patterns - rhymes, onomatopoeia, alliterative pairs - still without having to worry about the ‘meaning’ of the text itself. In this way, you will be able to have the children engaged in discussing ideas and playing with words, such that once you start looking at the poem itself, they are ‘warmed up’ and ready to start writing in a similar way:

The Dark The dark is a dragon Big and black He roars like a lion With a crunching jaw Fierce face All through the night he watches and waits In his sleepy cave Until in rage he awakes He roars and rumbles And breathes blazing fire Into the dawn of the day Tom, aged 10 Winter The winter is a snarling wolf, Biting the ones who disturb it, Rewarding the one who serve it, With cold refreshing snow. But on a warm winter's day, He cowers as the acidic heat, Burns into his body, Ow, ow, ooow! he cries. But on cold days of December, He crosses his domain, Spreading like ice, Howling, howling all the time. And as the winter ends, His eyes shine with sadness, And he slinks down and down, To places men will never go. Ben, aged 10 The Snow Hippo The hippo is a raging winter. Its teeth are splinters, The snow growing over time, Eventually ‘gone’. It is all mine. The size is overwhelming Swelling with snow. It will pounce only if annoyed, The wind moving it all the time. No void can move it, Only heat can. Hugh, aged 10 The Night The night is a lion’s jaw Shutting like a door slammed loudly. Wham! And you can’t see a thing. The night plays tricks on you Like a lion: Quickly. Jim, aged 10 The Eagle The eagle is pure gold. With his great and glimmering beak He soars over the mountains at midday. At night he sledges down the white snow In a blaze of shining light Like a king on his golden toboggan. William, aged 10 (SATIPS Poetry Competition 2011, Highly Commended)

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI currently teach English, French and Philosophy at St John's College School in Cambridge, UK. I am also Head of Poetry and have been inspiring young people to get reading and writing poetry for over 16 years. Archives

April 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed