A place What is a place? A space Or something special. The Nobel prize would say Molecules of air Atoms of oxygen. But that is a space. Maybe a place has to be lived in: A nest filled with blue eggs Or a lake of filigree dragonflies. Maybe emotion can live there In a baby’s cot Or a graveyard of red poppies. Maybe it is inside your head, A retreat, A place where you feel safe. But whatever a place is Where is it? Anna, aged 12 Some of the poetry which endures the most in the collective public imagination is that which evokes a sense of place. But, as Anna’s poem above reveals, a place is not quite so fixed and definable as we might at first think. Consider for how many people the word ‘Adlestrop’ would be entirely meaningless but for Edward Thomas’ sixteen simple lines: ‘Adlestrop’ by Edward Thomas Yes. I remember Adlestrop-- The name, because one afternoon Of heat the express-train drew up there Unwontedly. It was late June. The steam hissed. Someone cleared his throat. No one left and no one came On the bare platform. What I saw Was Adlestrop—only the name And willows, willow-herb, and grass, And meadowsweet, and haycocks dry, No whit less still and lonely fair Than the high cloudlets in the sky. And for that minute a blackbird sang Close by, and round him, mistier, Farther and farther, all the birds Of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire. from Poems (1917) The number of people who have actually been there, when compared to the number who know it only through the poem, must be tiny, and yet, when we do read the poem, we do ‘recognise’ it. Not literally, of course, for the majority of us, but as an experience of place. We have all been to places that resonate with us, through connection to distant memories, through a curious sense of déjà vu, through a sense of emotional belonging or through the deliciousness of the new. Children are no exception, and whilst their range of experience of different places will inevitably be less than that of most adults, their ability to convey a sense of place, either through memory or imagination, can help to create real poetic power. Year 1 pupils at St John’s recently visited the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge. To complement their classroom studies of Antarctica, they also worked with me to come up with their own poetic responses to the topic. Although they were in the early stages of learning to write, this certainly did not hold them back, and given the means to express their ideas figuratively and a structure on which to hang their words, they were soon able to work individually, in groups or with adult assistance to produce some great poetry. We started not by looking at words at all, but by listening a sound clip of an Antarctic storm, with the children trying to guess what they were hearing and to describe it in interesting ways, but without my telling them what exactly they were hearing. Some of them thought it was indeed Antarctica, but some suggested that it might be the ocean, whilst others thought it might be a very noisy motorway. When ideas like these were suggested, I made a note of them on the board and we discussed them in closer detail. What particular things did they hear that made them think of these places? Without having to tell them to do so, they were launching straight into the use similes and personification, e.g. “I can hear screaming tyres”, “The waves are roaring like an angry lion”, “I can hear a pack of wolves howling because of the cold” etc. By allowing this open-ended guessing-game approach at the start, the seeds were sown for a broad range of images and points of comparison. Had the lesson started with “We are going to listen to a clip of Antarctica”, this would almost certainly have narrowed the children’s thinking down to preconceived, literal ideas of ‘what Antarctica is like’. Instead, the aim was to keep the children’s mind open to all possible imaginative connections, to let them see that, yes, that does sound like an ocean and, yes, that could be a motorway. We then watched a video of the same clip, and this time focused on the visual aspect. Although the cat was now out of the bag in terms of what topic we were dealing with, it was interesting to note that just having those few moments of thinking about the sounds of motorways, oceans, jungles, hurricanes, mountains, or whatever had gone through each individual child’s mind, now allowed them to feel free to do a similar thing with what they could see. Numerous suggestions were forthcoming, for example, about how the snow being carried horizontally in the gale looked “like the white hair of an old witch”, “fierce waves” or “big white sharks’ teeth”. This ability to make sophisticated figurative comparisons seems to come naturally to children this young if done in as a group and in a spoken context and I was impressed to see how many of the ideas they had come up with in these early stages of the hour-long lesson were retained right through to the final stages once they got down to the business of writing. Certainly it had helped them to have audiovisual stimuli; in addition to the video clip, I put together my own simple Antarctica poem in the form of a slideshow juxtaposed with engaging images, that the children recited back slide by slide as I read it to them: The Ice King You may not have noticed me, Minding my own business Down here At the bottom of the Earth Like a speech bubble stuffed With snowy silence… Ignore me at your peril! I can impale you on my ivory tusk. In my cold, clutching claws I can snatch the sneaky, summer sun And stop him from slinking away. Or I banish him north for many a month And just keep my maiden, The milky moon, for company. And make her green fairies dance In the garden of my mind. I send out my warriors to scour the sea, In defence of my kingdom, Each one a bullet in search of a target. While my strange ballerinas swirl their skirts in the darkness, Trapped behind glass until I set them free. I'll drop not one tear of pity On my wind-parched valleys, However loud they may howl. And with the fire in my belly I'll cough flames from deep down To torment the terrified air. I could chew you to pieces With my tyrannosaur teeth. Or rip you to ribbons In one roar from my thundering throat. Rivers stand still at my command And cower as they gaze up At my glittering crown. Yes, down here, I am king. Ignore me at your peril... One of these days I might be coming to get you... Splitting a poem up in this way makes it so much more ‘digestible’ for younger children and they can take the time to pause, think and discuss each idea before moving on to the next one. Incidentally, I cannot recommend strongly enough having a go at writing for your pupils as a means of motivating them. If writing a whole poem seems daunting, just a line or two will help both to get the idea across to the children and will inspire them to emulate your example. It doesn’t have to be worthy of the T S Eliot prize. Just showing them that writing can be fun, that you enjoy it and that having a go is more important than ‘getting it right’ should be enough to give even the youngest learners the confidence to get writing in groups or independently. As Nicholas Guinn says in his chapter of Making Poetry Happen: “It is [...] important - for many pedagogical and ideological reasons - that teachers should write, and share what they write with their students (Andrews, 2008; Ings, 2009; OFSTED, 2009). [...] Sharing one’s own poetry with students can also help to demystify what might otherwise seem to be an arcane process and - perhaps most important of all - reintroduce into the classroom the words which Philip Pullman (2003) felt were missing from early Literacy Strategy documents: fun and enjoyment” I always feel a creeping sense of embarrassment when sharing my writing with children, if only that I know that I prefer the honesty and freshness of their writing, untainted as it is by self-doubt and self-criticism. However, as soon as I remind myself that I am sharing it not for its inherent quality as poetry, but rather to help others to learn, to emulate and to aspire, I realise that my moment of self-consciousness is worth the fleeting pain, particularly when it helps to get children writing like this: Antarctica Antarctica is a sword cracking through the ice Antarctica’s crown is mountains Hard like a diamond Antarctica can rip you apart Icebergs are crashing Antarctica eats big ships It stops the sun going down. Olivia, Jesse, William, Tabitha, Edmund, Archie (aged 5) Antarctica Antarctica is a snow queen wearing an icy crown She has a sparkly dress Silky cold skin Snow bright like the shining sun. Isla (aged 5) Notice how the use of simile, metaphor and personification has come naturally to these children, more so than it does to me. Onomatopoeia (e.g. ‘cracking’ and ‘crashing’), alliteration (e.g. ‘...sparkly...Silky cold skin/Snow…) and even assonance (e.g. ‘rip’... ‘big ships’) are all similarly in evidence. Whilst they may not fully understand or appreciate it, here is evidence that very young children do possess an innate sense of the music that exists within words and they are able to make clever choices in order to achieve effects that resonate with the listener/reader. ‘Polar’ by Gillian Clarke When we look at poetry by older children, it is hardly surprising that this natural affinity for language which has been with them for so long is able to produce some startling work, provided the appropriate skills have been exercised and honed in the interim. By way of example, Year 7 children at St John’s had the opportunity to visit the Scott Polar Research Institute for a poetry workshop with poet-in-residence Kaddy Benyon and me not long after the Year 1 children had paid their visit. They explored the museum, handled exhibits, found out about their origins and how they came to be here in this place. They then chose one particular exhibit and, inspired by Gillian Clarke’s childhood recollection of a polar bear skin rug, their task was to tell the story of the exhibit in the form of a poem. During their writing session at the museum, they took notes and made a start on structuring their ideas, but they were then given three or four weeks in which to revisit, edit and complete their poems, allowing them to develop slowly and ‘organically’. They shared electronic versions with me and the rest of the class throughout the process; that way, we were all able to make suggestions, ask questions and offer encouragement and criticism in order to help the work to improve. Here are some of the finished results: The Airship “Norge” When the airship ‘Norge’ made its expedition to the North Pole in 1926, the local Inuit were baffled, having never seen anything like it before. Some even thought that it was a god… The new king glides over his domain, Ready to rule, Ready to lead. His giant cetacean head acknowledges his newest subjects, And recognises their flaws, Their dreams, Their fears, Their hope. Engine, Check. Flight Course, Check. Balloon intact, Check. Discreetness, Negative. Nation? Inuit, Canadian, Advanced? Negative. Threats? Negative, sir. After the God has seen his loyal peasants, He moves on, Satisfied with his impression, He decides to move on, See the tribes to the east, The west, The north, Maybe even the south, Where the men wear black seals, And the women wear snowflakes. Change course. Yes, sir. Where to, sir? East. Co-ordinates, sir? As soon as we find civilization... There is civilization here, sir. Modern civilization! Yes, sir. Now the God has gone, No more of him is seen. Shamans say they talk to him. His voice is low, Deep, Like the icy waters, In which his lower forms swim. They call to him, Offer water to him, Offer meat to him, Offer praise to him. George (aged 12) Slippers They hold and comfort the weary and they disagree with the cold. Even though the caribou is dead life still floods through them. Grandpa adores them with all his heart, But I would prefer the caribou alive, Running free and bounding in the snow Instead of silencing his sorrow. I remember touching his nose that felt like rough honeycomb And as I watched him playing I thought I heard him laugh. The scarlet felt that lines the slippers Reminds me of the scarlet blood that stained the snow And my Grandfather’s continuous snore Reminds me of the caribou’s soft grunts And I only now begin to realise that the caribou is still with me Reflected in my own eyes. Mia (aged 12) Letter An aging man hugging onto life, His last strength poured into his letter. Does he not know his words await tears? His determination to finish makes him stubborn. His words trickle onto a page like teardrops, His last lines of life, his letters of love. His frozen lifeless body alone, spiritless. All is gone, resting in peace, but for his letter. Scott’s lifetime of ice concealed on a page Like a bird trapped in a cage Was death his biggest enemy or was it words? Did he let those words of defeat run over him? The patchworked mind full of paragraphs, Scott in his perplexed state of mind, Lost in those words. For him it felt like forever, Just him and those words perishing together Eleanor (aged 12) The Frozen Biscuit Wrapper The last hope of a hungry man The phantom of the biscuit, Long gone Trapped in stone cold frigidity Frozen to a dead man’s tomb Corners flapping feebly in the roaring whiteout Waiting, waiting for the sun For the comfort of caressing rays Dreaming of release From a long, long, wait. But it’s still there On the bottom of our globe Affixed to a grave Looking out at the bright light Waiting, day in, day out For a new life and purpose A new biscuit. Laura (aged 12) The Canoe Gliding along through a barren waste The carved paddle I pull myself through the chilly waters I will die if I spend a minute below this land of ice floes Inside its freezing, churning belly. The sleek frame, covered in seal hide, One leak and I’ll never go home I will live in the land of the dead Under the frozen wastes Of a land I know so well Everything in reach Even a floating map so if it’s dropped I’ll not be lost A paddle, my food, my water, my spear... They will last me for eternity Rupert (aged 12) Clearly, direct contact with genuine artefacts has inspired these young writers. They may only have been at the museum for two hours, but their imagination has been transported to the spiritual home of their chosen subject matter and their interest in it has driven them to find out more about it, to bring it to life again within its original context. This illustrates perfectly how the use of objects can help to elicit convincing poetic renderings of places to which you cannot physically take your pupils. A favourite dictum of teachers of creative writing to their students is: “Write about what you know.” However, introduce them to something (or somewhere) totally new and, provided you have given them the time and the means to engage with it and form an emotional connection with it, you may well find that they are just as capable of evoking it as they would be able to do with, say, their garden or their bedroom. Indeed, I agree with Ted Hughes’ point in Poetry in the Making, his seminal handbook for teachers of poetry, when he says: “It will usually be found that children write more rewardingly - both for themselves and for the reader - about strange or extreme landscapes than about anything they know well. It is as if what they know well can only become imagination, and available to the pen, when they have somehow left it. Deserts, steppes, the Antarctic, the moon, all come more easily than the view from their bedroom window.” One possible further reason as to why children today are capable of writing convincingly outside of their own experience is the prevalence of the internet in their day-to-day lives. With information about anything and everything at their fingertips, children can and do find out what they wish to know about the world around them much more easily than they would have been able to do at the time of Hughes’ writing. They no longer rely upon their parents and teachers to tell them what they don’t know, or indeed, how to go about finding it out. Their explorations in cyberspace are every bit as real and meaningful as the explorations of dusty attics, rock pools and treetops that previous generations would have thought of as the staples of childhood discovery. Thus, whether or not a child has been fortunate enough to have walked down the streets of Tokyo, watched the sun setting over the pyramids of Giza or watched the northern lights shimmering through the glass roof of a Swedish igloo, they are now empowered to write about it in ways that most of today’s adults can never have imagined doing at their age.

0 Comments

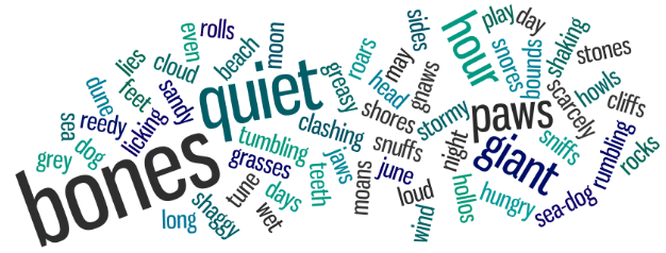

‘City Jungle’ by Pie Corbett Pie Corbett’s ‘City Jungle’ is a wonderful poem for encouraging children to observe the world around them in original and exciting ways. I have used the title as the inspiration for a slideshow lesson starter, in which each slide features a city picture juxtaposed with one from a jungle. (Spending ten minutes before your lesson trawling Google Images for suitable pictures will quickly reveal interesting points of comparison to which you will be able to draw the children’s attention.) For example, a photo that I came across depicting entangled rainforest lianas went particularly well with a photo of the interwoven night-time carriageways of Spaghetti Junction. When shown the two together and simply asked to comment, before even any mention of poetry had been made, the children immediately began to volunteer their own similes and metaphors which would later help to form some anchoring ideas for their poems. We looked at another five or so similar juxtapositions, using not only the city/jungle pairing, but also other man-made/natural comparisons, e.g. traffic jams/herds of zebras and wildebeest; empty city streets/Sahara desert sand dunes; skyscrapers/Giant Redwood trees etc. Many of the points of comparison are, of course, obvious, but it is this very simplicity that helps to open up the mind of even the most literal-minded child to the possibilities of metaphor. If they can see for themselves how ‘x’ can be (like) ‘y’ with the help of a visual stimulus, the challenge of putting it into words becomes much less daunting and, in all likelihood, much more fun. Moving on to the text of ‘City Jungle’ itself, there is much useful mileage to be had in asking the children work in pairs, groups or as a whole class to discuss exactly what the various figures of speech are doing. Sometimes there will be general agreement amongst the children; sometimes there will be considerable debate and differences of opinion. For example, the children will tend to agree as to the meaning and effect of ‘the gutter gargles’ or ‘A motorbike snarls’, but other lines such as ‘Rain splinters town’, ‘hunched houses cough’ and ‘dustbins flinch’ are more open to a variety of possible interpretations. With enough time given to discussing the variety of possible ways in which Corbett brings his city to life through the extended jungle metaphor, it should be possible for the children to then move on to developing their own ideas. Joe, aged 11, decided to compare our school - which at the time was undergoing some major construction work - to a zoo: Is It Still School? The eagle crane strains to eat the chain Then spits it out again Navy blue netting lurches like ruined spider webs Turtles wander for roofs The green wall – the prison barrier - stands guard Stake-like scaffolding sways Pneumatic drills bay like lions School will never be the same again. Joe, aged 11 Camillo, meanwhile, focused upon his native New York city and, without making any direct allusion to one particular point of comparison, created a collage of living similes and metaphors to give an impressionistic view of the place: New York The emerald park glittered in the sunlight, As seagulls soared overhead, As the waves of the Hudson swished and swashed, As people swarmed like ants over the colossal roads The skyscrapers like hands reaching for the sky, The museum’s noise was like a rhino’s wrath, As barges steamed down the rough river, And the tiny lighthouse, spraying light, even in the darkest of nights. Camillo, aged 10 ‘A Martian Sends a Postcard Home’ by Craig Raine One final method by which it is possible to get children spontaneously creating their own similes and metaphors without the need for over-explanation is to make the following little philosophical detour: “If you weren’t a human being, how would you make sense of the world?” Once this question is introduced, it does not take the children long to start realising that, without recourse to language, memory and shared experience, understanding and explaining what ‘a chair’, ‘the sky’ or ‘anger’ is becomes something of a conundrum to say the least! However, this is precisely the kind of problem that children revel in trying to solve. Raine’s 1979 poem illustrates the idea beautifully. By granting his Martian a reasonably thorough command of the English language, Raine is able, in his various snapshots of Earth as seen through alien eyes, to create a guessing game for the reader, whose job it is to work out the various things that the alien is describing for the folks back home. The use of the proper nouns ‘Caxtons’ (to signify books) and ‘Model T’ (to signify cars) helps to convey both the Martian’s partial grasp of the facts and his ability to perceive things outside of human time constraints and rational thought. Names from the past co-exist with more modern terms like ‘television’. There really do appear to be ‘ghosts’ within machines and the lines between the senses are blurred: ‘everyone’s pain has a different smell’. Every time I have used this poem with children, the ‘craziness’ of the alien’s interpretation of the world - which somehow just about makes sense when the human ability to abstract and empathise comes into play - has never ceased to intrigue them and to inspire great writing. Having read through the poem together and discussed what we think each of the things referred to by the Martian might be, I like to show images on the interactive whiteboard, juxtaposed with the relevant lines of the poem. That way, we can discuss in closer detail why the Martian has interpreted each thing in his particular way. When he gets something wrong, why does he do so? Are his errors in understanding explicable? Does he, in any sense, interpret anything ‘human’ in a more interesting way than we ourselves might? (The final lines dealing with the alien take on dreams are ones which many of the children have felt to be particularly apposite.) A way of extending the fun before getting down to the writing might be to come up with some ‘Martian’ interpretations of your own, either prior to the lesson or spontaneously, and ask the children to guess what you, in the guise of the Martian, are thinking of, e.g. ‘Walkers are fragile bent suns that hide in silver Until they are found. They disappear down deep tunnels, crying for help.’ (CRISPS) The use of brand names, echoing Raine’s use of ‘Caxtons’ and ‘Model T’, is something that really fires the children’s imagination, particularly where words with contrasting original and newer meanings throw up interesting or comical ambiguities, e.g. ‘apple’ vs ‘Apple’: A Martian Sends A Postcard Home Apple: a strange fuzzy thing with a bright blue skin Small buttons to click The noise that comes out with the human’s strange movement Putting little wires into their ears and listening to it speaking Tickling its tummy Making it sing. Matthew, aged 10 A Martian Sends a Postcard Home ‘STAEDTLERS’ are wasps with a sting of grey And for reasons unknown the humans torture them on purpose By skinning them alive. This makes the STAEDTLER angry and find the sting’s mark. HPs are cloning devices that suck people in and double them out. Wires are matings between two electronic beings. Google is the smartest man in the world Trapped in a Zeus so everybody asks him their queries. Tom, aged 10 A Martian Sends an E-mail Home Jimmy Choos are chairs for feet when they are Walking out of the hollowed-out stone. Clouds are big white animals that sleep in the sky When they cry they go grey, And tears pour down. Tefals lie down on big boards, then when are tired they sleep. When they want to wake up they steam So the human picks it up Again and soothes it to sleep. A baby is a machine. When it runs out of battery It makes a nasty beep. The human plugs in the odd charger Inside. Then it stops beeping. Ella, aged 11 The Strange Beings The strange beings lounge around like they have no care in the world While I keep a weary eye out for predators. They replace their own eyes with dark, shiny ones In which the world is trapped. They bake in the sun, Changing colour as they get hotter and hotter. Before they get so hot that they would turn to ash, They swim like me, praying in between the strokes. They wear patterned over-skins, Trying to hide within them. But their arms and legs are too big to fit. Love is when the strange beings stare at each other with longing in their eyes. A longing to be unstuck from the other being’s hand. They swing their arms about, Trying to free themselves. But all the while, a curved line is painted across their face. Emma, aged 10 The World Through a Dog’s Eyes My owner leaves Off to the light home in the small world that moves. I run and hit the air, An invisible force which tall tailless calls “glass.” The great yellow sphere has begun its journey around the out. Some lights Many tall taillesses form a pack. I only eat at dark when tall tailless has finished his stomach stuffing. In the middle of the dark The great white sphere begins its journey. A barrier guards where tall tailless sleeps. I am alone now in my sleep place. I shake as pictures invade my head. I do not understand. Isaac, aged 10 The activity is not limited to an imagined alien’s view of the world; as Isaac chose to do, the view of an animal trying to make sense of human behaviour can be just as, or even more, powerful. The process that the children go through with this poem of trying to ‘unknow’ the world around them, to look at it without the benefit of an understood context and prior knowledge, liberates them enormously to be utterly original and inventive. After all, the alien/animal that they are imagining is entirely their own creation; nobody can rubbish the subject’s account of its own experience by saying: “An alien wouldn’t think that!”, “A dog wouldn’t feel that way!” etc. Thus, the child’s innate fear of ‘getting it wrong’, which can be a real block to creative expression, particularly among children with perfectionist tendencies, really does not come into play with this activity. Provided the comparisons made in the poem can be understood by the reader, however vaguely, the writer has succeeded in painting a picture of the world through non-human eyes. A further joy of this activity is the eagerness that the children tend to show about sharing their work. They are always highly motivated to see if their friends and if you, their teacher, can work out what their alien/animal is referring to in its ‘postcard’. Rather than having to cajole them into reading their work aloud, I usually find that all hands shoot up at once and we have to save a few eager readers to have their turn in the following lesson. By reading their work to their peers, the children have the opportunity to think about their choice of words as they deliver them. They might realise that such and such a word might be better replaced with another one. If they haven’t quite finished, they might have a sudden epiphany about how to do so. One of their friends might comment positively on a particular metaphor or a rhyme and this might motivate them to edit further in order to draw more attention to it. Most importantly, perhaps, they will gain the sense of achievement that their words have gone ‘out there’, rather than merely been stuck within the customary limitations of the teacher-pupil dialogue. However important the feedback of the teacher may be, the feedback of peers should never be underestimated, particularly where creative endeavour is concerned. If children can understand what interests their peers about their writing, it will help them to develop their skills further with their audience in mind, which can only be a good thing.  ‘The Sea’ by James Reeves The simplicity of James Reeves’ opening line of ‘The Sea’ is what makes this a particularly useful poem for teaching children about the power of metaphor. The poem almost seems to write itself after this basic premise, with the young reader’s mind already primed and excited to embark on the journey aboard Reeves’ train of thought. Indeed, this is one of the many poems that I have used with which the first 15 minutes of the lesson are often happily and productively spent bouncing around the implications of this initial line: Do you agree? Why? Why not? In what way is the sea a ‘hungry dog’? What does it do? Why does it do it? etc. The questions arise quite naturally and the children - whatever their age - always respond with plenty of creative and original ideas, prior to ever seeing anything other than Reeves’ opening line. Perhaps this comes down in part to its vocabulary, which is accessible to all and therefore linguistically unthreatening. I would argue, however, that the primary reason why this opening line hooks the young poet is that there is an innate openness to metaphor in most, if not all, children. The very use of the metaphorical ‘is’ as opposed to the simile-generating structure ‘is like’ immediately challenges the child to think more deeply and, in doing so, they are quick to tap into the noises, smells, colours and shapes of the sea that make the dog comparison resonate. When they then look at Reeves’ actual lines, children are quick to notice the long, low sounds of the sea echoed in the long vowel sounds - ‘rolls’, ‘hour upon hour’, ‘howls’ - and the irregular but insistent rhyme scheme - ‘bones/stones/moans’, ‘jaws/gnaws/paws/roars/shores/snores, ‘sniffs/cliffs’ - that evokes the varying rhythms of the waves. Assonance, alliteration and onomatopoeia play central roles in conveying the sounds of the sea in this poem and valuable time can be spent not merely in identifying where these are within the poem but what exact effects they are creating. I recall one Year 5 child mentioning that the lines - “And 'Bones, bones, bones, bones! ' The giant sea-dog moans”

The Forest The forest is a lonely cow Lumbering and brown. She swishes, swishes the sky all night. With her smooth teeth and slow jaws Hour upon hour she chews The echoing, dark trees, And lows, lows, lows, lows! The lumbering forest-cow lows, Standing stock still On her huge tree-trunk legs. And when the morning wind is hollow And the sun sways in the windy day, She stays on her feet and rustles and chews, Shaking her fleas, wanting peace, She groans and moans long and slow. Ingo, aged 10 Much of what makes ‘The Sea’ such a memorable poem comes down to the clever use of repetition and rhyme, so as to provide a constant reminder of the recurrent sounds of the seascape. As Ingo has done in his forest poem, finding ways of conveying the sounds of a place through combinations of onomatopoeia, alliteration and assonance (‘swishes, swishes the sky all night’/’lows, lows, lows, lows’/’She groans and moans long and slow’) really appeals to the child’s innate fascination with words as playthings to be put together rather like Lego bricks to create colourful, crazy structures, as opposed to using them simply to string together units of meaning. Like Reeves, Ingo has ‘built’ his forest metaphor from a montage of interesting sounds and images, allowing him not to get bogged down with literal interpretation. To further facilitate children with tapping into this technique, a very useful app to consider using is www.EdWordle.net Insert any text into it and you can instantly create a ‘word cloud’ of it, in which the more often a word occurs, the larger it will appear. Here is a word cloud of ‘The Sea’ with common words (e.g. ‘the’, ‘and’, ‘but’) removed: Word clouds such as these can be used to introduce a poem, in this case, for example, by asking the children to make suggestions as to what the poem represented by it might be about. The prominence of ‘bones’ and ‘paws’ might well lead the children to identify the dog theme fairly quickly; those who then look more closely to find ‘cliffs’, ‘sandy’ and ‘beach’, for example, will start to ask themselves questions. Is this a poem about a dog running around on a beach, maybe? Already, the images of ‘dog’ and ‘sea’ will be brought together in the child’s mind and everyone can set to work on spotting patterns - rhymes, onomatopoeia, alliterative pairs - still without having to worry about the ‘meaning’ of the text itself. In this way, you will be able to have the children engaged in discussing ideas and playing with words, such that once you start looking at the poem itself, they are ‘warmed up’ and ready to start writing in a similar way: The Dark The dark is a dragon Big and black He roars like a lion With a crunching jaw Fierce face All through the night he watches and waits In his sleepy cave Until in rage he awakes He roars and rumbles And breathes blazing fire Into the dawn of the day Tom, aged 10 Winter The winter is a snarling wolf, Biting the ones who disturb it, Rewarding the one who serve it, With cold refreshing snow. But on a warm winter's day, He cowers as the acidic heat, Burns into his body, Ow, ow, ooow! he cries. But on cold days of December, He crosses his domain, Spreading like ice, Howling, howling all the time. And as the winter ends, His eyes shine with sadness, And he slinks down and down, To places men will never go. Ben, aged 10 The Snow Hippo The hippo is a raging winter. Its teeth are splinters, The snow growing over time, Eventually ‘gone’. It is all mine. The size is overwhelming Swelling with snow. It will pounce only if annoyed, The wind moving it all the time. No void can move it, Only heat can. Hugh, aged 10 A Volcano A volcano is like a hungry cobra Vicious and violent He lies watchful, waiting to strike. Tom, aged 9 The Night The night is a lion’s jaw Shutting like a door slammed loudly. Wham! And you can’t see a thing. The night plays tricks on you Like a lion: Quickly. Jim, aged 10 The Eagle The eagle is pure gold. With his great and glimmering beak He soars over the mountains at midday. At night he sledges down the white snow In a blaze of shining light Like a king on his golden toboggan. William, aged 10 (SATIPS Poetry Competition 2011, Highly Commended) One longstanding favourite activity of mine which was inspired by ‘The Sea’ and which has worked particularly well with children at the younger end of the age range is the ‘randomizer’ method of metaphor/simile building. For this, I use tactile objects such as ping-pong balls, which help to make the activity seem like more of a ‘game’ than a ‘lesson’ in the traditional sense. The children simply take a ball from each of three boxes. The thirty or so balls in the first box have random concrete and abstract nouns in the singular form written on them, e.g. ‘rain’, ‘joy’, ‘life’, ‘summer’ etc. The five or six balls in the middle box have either ‘is’ or ‘is like’ written on them. In the third box, there are again thirty or so nouns, often together with a modifier, as per what will work grammatically, e.g. ‘a hurricane’, ‘the ocean’, ‘my bedroom’, ‘candyfloss’. By selecting their three balls at random, the children are given a ready-made simile or metaphor to use as a starting point and to develop in their own way. Often their selection will not make immediate sense and there will often be fits of laughter and protests along the lines of: “Rain is like my bedroom! That’s just silly!” However, with a little encouragement not to reject their selection in favour of a new one, but rather to take the idea away and play with it in rough for a few minutes, there can often be some astonishing results: Happiness My happiness is a child Rushing home to tea Sorrow My sorrow is rain Falling steadily in the night Fear My fear is a sprawling spider Creeping silently behind the enemy Prepared to pounce Breath held Fangs exposed The venom seeps into the withered veins Ollie, aged 9 What is the Sun? The sun is a giant Yorkshire pudding Served piping hot It is a glinting pendulum Dazzling our eyes The sun is a fishing hook Lowered down and down Then hauled back up again But it never catches anything The sun is a large luminous eye Watching over the universe It is a discus Flung from the depths of the deep black sky Benedict, aged 9 What is a River? The river is a blue fist Pounding through the mountains It is a whipping rope Lashing out to sea The river is a deadly blade Slashing countries in half It is a dying man’s lifesaver Glistening in the sun Henry, aged 9 Similes Love is like an avalanche, It builds for years and falls in minutes. Boredom is like a stone, It never changes. Frustration is like the ocean, It shows you knowledge and yet you’re never satisfied. The future is like a candle, But the wick is still to be lit. Joy is like a lighthouse, It shines when needed. Thomas, aged 10 Thoughts A thought is like a story; you never know where it will end. Jealousy is like a flame; it spreads and engulfs your mind. Desire is like ice cream; the more you have the more you want. Frustration is like a star; when it collapses, it sucks you in. The past is a winding road; it spirals around you and makes you who you are. Sebastian, aged 9 (SATIPS Poetry Competition 2013, Years 5 & 6 Winner) Time The future is like ice. You never know when it might break. You might slip and fall, You could stand tall and proud. Beneath the ice hidden secrets could be lurking in the depths. The present is like water. It flows freely and explores. It makes its way through storms of hardship And flows through the clear sky of happiness. The past is like steam. One second it is the water so clear, The next it has turned into thin air, Lost from sight. Emma, aged 10 These poems were written by children across the full ability range, and, as can be seen, each one has its own particular merits in terms of extending the metaphors and similes such that a seemingly inapposite comparison becomes meaningful through deeper exploration. The children were encouraged to really delve into how one randomly selected noun could be compared in some way to another, however difficult that task may seem at first glance. Repeatedly asking themselves how or why X ‘is’ or ‘is like’ Y gave them a model by which to extend their ideas to full effect. By approaching the exercise as a playful philosophical challenge, the writers were all the more driven to come up with original thoughts and, without any need to labour the explanation of metaphors and similes, they got straight to the intended business of creating them for themselves. They were allowed to work on numerous discrete ideas, returning several times to select new ping pong balls; alternatively, as Emma did, they could start with a single comparison (in this case, ‘future’ = ’ice’) and then extrapolate their own equivalents from it (‘present = ‘water’ and ‘past’ = ‘steam’). As I have suggested previously, there is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ way where children’s writing of poetry is concerned; having the flexibility to allow the children to go off in their own direction from a common starting point or towards an agreed goal should always prove successful and pleasurable for all concerned. What particularly interests me about the poems produced by the children engaged in this activity is how clearly one can detect the preferred modus operandi of the child in the finished piece. Those children with more of an impulsive learning style, will tend to be those whose work shows a colourful array of disparate and often unconnected images, which can create startling and exciting juxtapositions. Those children, on the other hand, who like to think through one idea slowly and thoroughly before moving on to another will tend to produce a more measured and coherent composition, going deeper into the underlying meanings. Neither end result is ‘better’ than the other, in my opinion. Indeed, the joy for me as a reader of poems written by children attending the same lesson lies primarily in the often striking differences that emerge between them.  ‘Mirror’ by Sylvia Plath Notwithstanding the occasional appearance of poems such as ‘Mushrooms’, ‘You’re’ and ‘Metaphors’ in poetry anthologies for younger readers, Sylvia Plath is a poet who would rarely be mentioned in the same breath as the phrase ‘children’s poetry’. However, as with my earlier examples of Philip Larkin and U A Fanthorpe, I am always willing to use a poem by a writer of abstraction and complexity such as Plath, provided that the underlying ideas are ones with which children can identify. (Even if the language is in parts obscure, all children will be able to handle the general thrust of a ‘difficult’ poem, provided sufficient time is given to class discussion.) ‘Mirror’ is a poem that goes back a long way for me, it having featured in the anthology that formed part of my GCSE studies, namely Touched with Fire, edited by Jack Hydes. It would never have occurred to me to use it with children if, on starting my first teaching job in 2000, I hadn’t rifled through all of my old school folders and found these, written when I was in Year 9: Meeting I turn on the taps And the steam hides my friend Behind a misty opaque window Of smoke. The only way I can bring him back Is to slap him And to smear my fingers across His cold and shapeless face. So why doesn’t he go away Or even slap me back? His glossy eyes give an icy stare And his smile is faked. His red face is washed And his hair combed into strange contortions Until we are complete. Then we depart from the strange window, To return some other time That we both know, But without a word spoken Between us. Mirror World The clocks go back in time and lights Stand upright from the peeling plastered floor Like lamp posts. Mirrors reflect Mirrors within Mirrors; An eternal row of military images which vanish Into the distance. The room revolves, Crashing ghostly figures into each other unawares. The room is like a house of cards Where Kings meet Queens in the middle But face away. Siamese Jacks, silently bisected and sewn together In sudden operations. In this mad world The boys wear blouses and the girls wear shirts. Extra-limbed aliens walk around as if human. We read in a foreign alphabet And write wrong-handed. Then the mirror moves And the House of Cards comes tumbling down. And so the memory was triggered. I had written these for my school’s annual poetry competition. Mrs Swigg, my English teacher at the time, had ventured over to the Science labs to borrow a box of the mirrors that they would use for the light reflection experiments in Physics lessons. For homework, we were to take two of the mirrors each and walk around at home or outdoors, observing the different effects that can be created by looking at the world with them. A mirror in front of one eye but not the other. A mirror slightly bent or twisted. One mirror placed at right angles to the other. I had spent a good hour driving my mother mad by walking around the house bumping into things and knocking antiques off tables, so absorbed had I been in this activity. And then, for the rest of the evening, I had drafted and redrafted ‘Meeting’ until I was happy with it. Next day, aware that the rules of the competition allowed everyone to enter two poems, I spent all of double Latin secretly holding the mirrors behind my textbook and reflecting them off the ceiling and a pack of cards that I had to hand (The card game ‘Spit’ was the big craze at the time.) By the end of the lesson, ‘Mirror World’ was finished and I thought I’d throw it into the mix as well, even though I thought ‘Meeting’ was the better poem, because I’d done that one ‘seriously’. However, to my amazement, it was ‘Mirror World’ that Mr Cash, Head of English, preferred and there I was, ‘Highly Commended’ for something I had written in fits and starts in the middle of trying to translate something about slaves and fields from our Latin textbook, Ecce Romani. What intrigued me on discovering these poems is that, without referring directly to Plath’s ‘Mirror’, my teacher had managed to get her pupils thinking like Plath, engaging with the world directly, physically and in a totally new way in order to write. When studying the Plath for GCSE, it had not occurred to me to look back at my own mirror poems and compare them, never thinking for a moment that they had anything to do with each other. After all, Sylvia Plath was a ‘proper’ poet and I was just someone who liked to show off with big words. However, looking back over my own writing at the start of my teaching career, I realised that, wherever my words came from, however good, bad or just cringeworthy they might seem now after ten years shoved in the bottom drawer, they paint a picture of who I was then and might be used to help my pupils put something of themselves into words. It occurred to me that, by showing children how one of the greatest poets of all time used the theme of the mirror and that anyone can create their own original response to the same theme, this might encourage them to give it a go themselves. So here is the task that I gave them: Read these two poems (‘Meeting’ and ‘Mirror World’,) together with Sylvia Plath’s ‘Mirror’. Then, use the mirror provided to spend a few minutes looking at the world around you.

Note down any ideas that occur to you in rough. Now, plan your own poem inspired by the theme of looking in (a) mirror(s). Don’t forget to think of the various different types of mirror that are used in everyday life. Remember that the poem does not have to rhyme if you do not wish it to. I didn’t tell them who had written the first two poems until we had read and discussed them together. This gave them the freedom to criticise and compare freely, without any fear that they would offend me with their opinions. Their observations were fascinating. They spotted things in my poems that I had not - pleasing and less pleasing word choices, unintentional alliteration, awkward syntax, interesting line breaks - and treated all three poems as equals. The name ‘Sylvia Plath’ does not, of course, resonate any more strongly in a typical child’s mind than ‘Anonymous’, so their analysis was not distorted by preconceptions (just like Plath’s own mirror). On telling the children - it was a class of Year 7 pupils on the first occasion that I did this activity - that I had written the two anonymous poems when I was fourteen, I could sense the atmosphere sharpen. I was half expecting them to say, ‘Oh, well they’re not proper poems then, are they?’ and feel somehow duped. Far from it. The instant response was along the lines of: ‘Right, I’m going to do that!’ and off they went: Mirror World As I stare at the mirror It stares back at me Its skin as pale as gruel. When you think of the world Inside a mirror You think of it Ever so cruel. Words have no meaning, Beginning is end, Paintings hang upside-down on the wall, Trees all grow downwards, Heaven lies in the earth, And aeroplanes begin softly to fall. Angus, aged 12 Reflection He is always there In every mirror, Distorted in each piece of cutlery, Faded, faceless, in every pane of glass Ready to replace me If I laugh, he copies A cold humourless clone He is only truthful But it is a half truth I almost have pity For one trapped in A cold, dark reflection. Aaron, aged 12 A Reflection I am the mirror on the wall With ornate frame of gold And strange temptations like a siren’s call To bend you to my careful mould There is no choice For me nor you I simply do what I was made to do You made me, took the decision To see yourselves backwards Tom, aged 12 Rain Mirror It forms as the rains come; Gathers when a myriad droplets Crash, exploding, to the dry ground. Slowly it seeps from the centre, Expanding, growing, covering the road With its silvery surface of reflection. Then the rains stop. The mirror stills, shines Its information brighter. The eye sees deeper, finding Changing pictures now Glimpses of a foreign world. And as the eye begins to marvel Drawn closer to this simple pool, A single stone, source unknown, Approaches, growing faster, gaining speed, Until, with a silent explosion, The world of the mirror shatters Into a thousand liquid shards. Paris, aged 11 The Mirror I am pinned to the wall and hang there, Thinking, reflecting, Watching, waiting, for something to happen For someone to come past, something to see So then they can see too. I bring disappointment, rarely joy, But cannot help it. It is strange how they are never satisfied. I seldom see a single soul that smiles. People pass, frowning and sighing And always come back, to sigh once more. Alex, aged 11 The Mirror Smashed, stained, abandoned, Lying in the attic covered in cobwebs, Unable to make a sound, Waiting, waiting Like an idea trying to come back to life, Hearing, hearing Only the occasional murmur and running On the downstairs corridor. Sometimes, sometimes Having hope, When a fine light shines on its face And then dimming. The sound of talking Echoing around the room like a cave And at night Hearing nothing, nothing But the sound of the cars And flashing light Streaming through the window. Grace, aged 11 Dancing in Anger I watch her twirl. Savagely tearing a hole In her world. She Becomes a blur of colour, Of light. I watch her stretch, Viciously creating line after Line through her hands, Her elbows, her shoulders. She is dangerous. I watch her bow. Her emotions still outside Her control, her body. She shakes and trembles. I watch her leave. She sends the studio Into darkness. I cannot Reflect anything now. Surely there is nothing there? Anna, aged 11 (Foyle’s Young Poets 2011, Highly Commended) This is just a small selection of what the children produced as a result of this session. All of them were given the opportunity to develop their ideas gradually over time, drafting and redrafting them electronically, in order to ease the process of perfecting the finished result. The ever-increasing use of IT in the educational environment is of enormous advantage to the creative process where writing is concerned. I always encourage the children to move electronic copies of their work over to shared folders as soon as possible, even if it is only in the initial stages of development. That way, they can seek advice not only from me but from all of their peers, as to which images and ideas work well, whether or not they should stick with the rhyme scheme that they have chosen, how they should bring their poem to a satisfying conclusion, and so on. Children respond very positively in my experience to this very open approach to writing poetry, and seeing each other’s work develop organically, far from encouraging ‘copying’, seems to elicit the very opposite, i.e. a desire to plough their own furrow and come up with something truly unique. As we discovered through the Mirror Poems activity, using a common thematic starting point and taking time to revisit the work in progress at regular intervals over several weeks produced a very interesting and varied collection of poems which sought to explore forms, influences and approaches in novel ways. |

AuthorSixteen years of teaching poetry to children have furnished me with a wealth of ideas. Do dip in and adapt any of these for your own lessons. Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed