|

Archaeopteryx fossil cast, taken from the Natural History Museum of Berlin's specimen © University of Cambridge animalbytescambridge.wordpress.com/2013/03/30/archaeopteryx-cast/© ‘Archaeopteryx’ by Gillian Clarke Few poets working today have done as much as Gillian Clarke to promote writing by children without explicitly writing for them. For me, it is this ability to communicate across the generations through her poetry and her teaching of it that makes Gillian Clarke such a fascinating poet to work with, both on the page and in person. Clarke gave a workshop at the University of Cambridge Museum of Zoology in 2013, in which a group of our Year 8 Bronze Arts Award candidates participated. The workshop was part of ‘Thresholds’, a project set up in collaboration between University of Cambridge Museums and Arts Council England to provide poets in residence at ten of the university’s museums and collections. The project provided a unique opportunity for poets to create tangible connections between objects and words, and to share them directly with an audience who might not otherwise choose to engage with poetry. All of the children whom we took to participate in Clarke’s workshop had an existing keen interest in creative writing and wished to include it within their Bronze Arts Award portfolios, alongside artwork, sculpture, design pieces and musical compositions. Within the framework of the two-hour workshop, they were allowed to examine and handle a number of the museum’s exhibits, including skulls, bones and even an egg which had been brought back from Darwin’s expedition on The Beagle. The museum curators gave detailed explanations of the objects and invited questions about them, whilst Clarke encouraged close observation on a metaphorical level: what does the object look like, feel like, smell like, sound like? The children could also wander around the larger exhibits - whole skeletons and glass cases with stuffed specimens - sketchbook in hand, drawing and noting anything of interest, with the instruction to choose one exhibit which inspired them to write. Having this level of freedom to interact with the exhibits helped to break down some of the ‘distance’ that typically exists for children in the museum experience. The ‘Do Not Touch’ injunction was refreshingly absent from the experience and, by placing an implicit trust in the children to respect the environment of the museum, the curators had freed them up to put the exhibits at the forefront of their minds, not rules and regulations. When it was time to start writing, Clarke told us about her favourite exhibit at the museum, the Archaeopteryx. She had not yet finished her poem about it, but told us why it had inspired her and told us some of the ideas that she would be including in her writing: “In my first hour in the exhibition gallery I saw what is still my favourite treasure. It is the fossil of a bird, with a perfectly preserved impression made by its wing-feathers, like when you play ‘Making Angels’ in the snow, lying on your back and sweeping your arms to make wings. The Archaeopteryx is the earliest bird fossil, the size of the magpie that just left its impression in the snow on my lawn. The snow-shadow will melt. Stone has held the Archaeopteryx for millions of years, like a photograph of the Jurassic period. It makes me dizzy, just thinking about it.” Her instructions for writing were simple: to make connections between the specimen as it is now and how it would have been when it lived, as she herself has done in the finished version of ‘Archaeopteryx’. The stillness of the object is given movement and colour through reflection on the life that it once had, through description of what a muscle, a bone, a tooth or a tusk was originally designed to do. This technique can clearly be seen in the children’s poems below, each of which shows careful consideration of the physiology underlying the history. African Elephant Ivory dancing in the marmalade light, Jawbone balanced with tiptoes, Rib bone spears splitting muscles, Jagged, jarring, Shoulder blades charging to defend the golden land Grey ageing cloth taut Azure irises flaring Bellows reverberate inside him The crimson blood, the helpless cry. Not again. Mind fixed on the sharp outline A spark was lit, an inferno awakened. Isabel, aged 13 Gecko A membrane of filtered light Looking through a window of curving bone Spindly features hollow with light A faded string of arcing transparencies Cradling tiny bones, the missing pieces of a jigsaw Splinters piercing the frail mouth The sun breathing light into its frail body Flicking through the sand, the musty dust scattering As it jolts the sharp notes of the speckled light Folded bones enclosed in a bracket of skittish vibrancy Absorbing the light from the cobbled sky Filling the gaps in its delicate features Its tiny brain scattered with racing thoughts The intertwining rims of bone flooded with light As it scarpered across the plain evading the night, Crashing the darkness with flecks of colour Mirrored precisely with tessellating curves You could never see the emptiness inside Because life filled the hollow places That pierced through to the outside Chloe, aged 12 The Badger The mouth, strong and tough, Teeth that interlock precisely. When the mouth is open, It will come down with the force Of an avalanche. When the jaw muscles contract, The icicles dig into the prey. Under the cover of night, The stalking of rodents commences. The cunning badger, Fooling the mouse into leading him to its nest. Huw, aged 13 The Darwin Egg Closed in the palm of your hand Chocolate brown, A crack down the middle Snaking its way across the surface. Not caused by nature, But the great man himself, When cushioning it in a bed. The spotted tinamu lies on her nest, Acting like a radiator to the egg, So delicate it will break at the lightest touch. She can’t wait until it hatches Her beautiful baby bird, Soaring through the air But, alas, that moment never came. Emily, aged 12 Tortoise Life flowed through its blood Like water Buried in the depth of distant life With only a handful of truths Left behind by Destruction or ruthless guesswork. Motion - caught, trapped: In cavity, Behind thought. Frozen in death Is the energy Dropped and lost in The shadows of those thoughts, Only few to be uncovered From the secrets They lie beneath. Jessica, aged 13 Whale Ear-Bone Broken bird, Like angel fronds, Carrying the burden of a Larger life. Sweeping shards Of Bubbleweight bone in The deadened, lonely Pressure Of not just water. In this unforgiving, impossible Life-place, It exists. Protecting from each powerful movement Its bearer makes, Oblivious, In the simple concentration of Survival, To the complex workings we Know. It is like solid air, Or concrete feathers. Isolated, it does not belong, The need of more. There is a purpose in Completion, but at a price; These fundamental fringes are only fragments, Lost within the Bigger picture of the Whale. Jessica, aged 12 Whale’s Earbone As you slowly run your hand over the whale’s ear bone, You feel the roughness, rigidness and smoothness. It almost looks like a foetus curled up, Or a silk woven purse. As you look inside it, it gets very smooth and deep. You can nearly hear the crashing of the waves, Or the crying of the gulls inside it. Its glimmery skin, Glistening and glazing, As it streamlines through the ocean. Guy, aged 12 For me, each of these poems beautifully captures the essence of the artefact in question as if it were still alive. None of the objects seem to be in any way confined to their museum and the writers have skilfully constructed a bridge between the ‘then’ and the ‘now’. If anything, this experiment in using the museum as a space for poetry illustrates how effectively children can assimilate the past into their present through the act of writing in a meaningful context outside of the classroom. A deeper understanding of the past can be embedded through direct creative engagement with it and this can only be a positive thing for the future both of the arts and of museums.

0 Comments

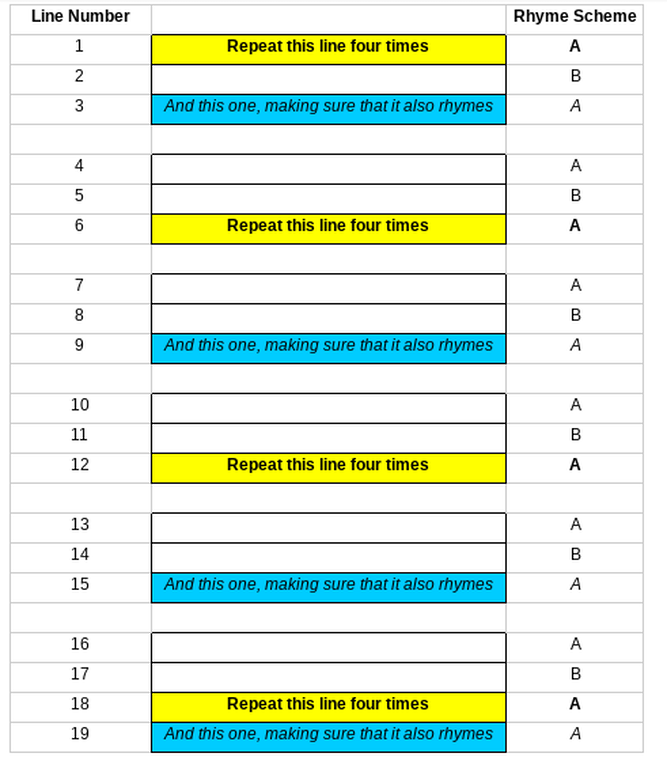

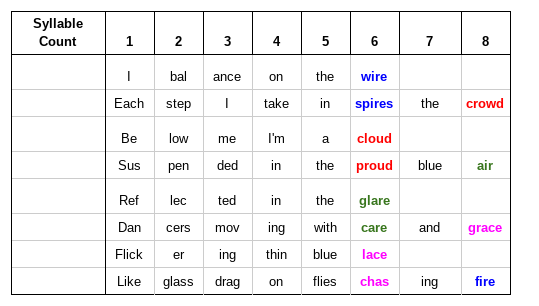

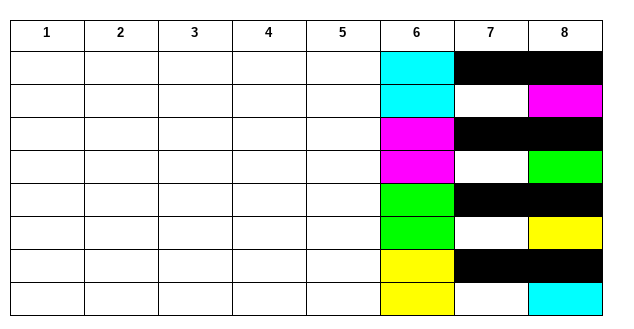

I often suggest to children that they should think of writing poetry as performing act of transformation. The shapes and patterns of day-to-day language are reworked and crafted so as to create something new. Similarly with the ideas that underlie the language. Whatever starts in the writer’s mind in the raw syntax of the thought process is changed by the application of poetic technique into something tangibly different, something magically enriched and rendered memorable. How this magic happens is, of course, impossible to pinpoint and is different for each and every writer. Just as any artist would struggle to explain how an initial idea makes its journey from seed to a fully grown, living artwork, the poet is similarly at a loss to map out the workings of the mind that result in a finished poem. For me, at least, the very concept of a ‘finished’ poem is something of a troubling one. Every time I revisit one of my own poems written for the purposes of teaching a particular form or theme, I am compelled to rework it in some way, such that, in some cases, the vestiges of the original piece of writing are few and far between. Just like a car which, over its lifetime, has had each and every part replaced, a poem has the paradoxical potential to be involved in an ongoing process of change whilst still, in some sense, being the ‘same’ poem. In this sense, I have often wondered if the very act of committing poetry to paper and publishing it in a ‘final’ form stands at odds with its true nature. For a poem to be truly ‘alive’, it needs to live alongside its writer and be free to change and develop at the writer’s will. Certainly, when hearing poets give readings of their own works, I love to listen out for the little alterations that they make. Some listeners, of course, would immediately assume that the poet had ‘made a mistake’ or ‘got it wrong’ if, at a subsequent reading, a change had been made from the published text. For me, pretty much the opposite is true: the current version is now the stronger claimant for being the true poem and, even if this version exists only for one reading before reverting to a previous form or changing to another new one, that is all part of what helps to make poetry a living artform. I like to consider the infinite possibilities that spring from the seemingly trivial word choices that poets make. What if Yeats had wished for ‘ten bean rows’ on Innisfree instead of ‘nine’? What if Shakespeare had compared thee to a ‘summer’s eve’ or ‘a summer’s morn’, rather than a ‘summer’s day’? What difference would it make if Jenny Joseph were to wear ‘yellow’ having grown old, not ‘purple’? Much of this, of course, is just the workings of mind that revels in wordplay, but the serious point here is that, when teaching poetry to children, the more their minds are opened up to the infinite possibilities that sit there before them on their enormous palette of words, the more scope there is for them to keep exploring, to keep learning and to keep enjoying the very act of writing poetry. ‘Transformations’ and ‘Proud Songsters’ by Thomas Hardy Transformations Portion of this yew Is a man my grandsire knew, Bosomed here at its foot: This branch may be his wife, A ruddy human life Now turned to a green shoot. These grasses must be made Of her who often prayed, Last century, for repose; And the fair girl long ago Whom I often tried to know May be entering this rose. So, they are not underground, But as nerves and veins abound In the growths of upper air, And they feel the sun and rain, And the energy again That made them what they were! Proud Songsters The thrushes sing as the sun is going, And the finches whistle in ones and pairs, And as it gets dark loud nightingales In bushes Pipe, as they can when April wears, As if all Time were theirs. These are brand new birds of twelvemonths' growing, Which a year ago, or less than twain, No finches were, nor nightingales, Nor thrushes, But only particles of grain, And earth and air and rain. On taking my first teaching job in London in 2000, I found myself living in a studio flat above a mouse-infested secondhand electricals shop, just a stone’s throw from the King’s Cross railway tracks. In the week that I moved in, I was deeply immersed in my brown-jacketed Faber Collected Poems of Philip Larkin and couldn’t help wondering if I had contrived, either by accident or design, to turn myself into Mr Bleaney. If this whole scenario were not already Larkinesque enough, I was soon to learn that the area hid one particular and unexpected connection to one of Larkin’s strongest influences, namely Thomas Hardy. I discovered this quite by chance on one of my summer strolls, which took me past the old gasometers to Old St Pancras Church, not far from Mornington Crescent. Within the churchyard, I came across an intriguing ash tree, around whose trunk are arranged a large number of old gravestones, radiating out like roots. It is known as The Hardy Tree. Hardy trained as an architect in Dorchester and, after he moved to London in 1862, one of his first jobs involved working on the excavation of Old St Pancras Church graveyard. Many of the graves had to be removed to make way for the route of the Midland Railway into the new London terminus at St Pancras. Hardy oversaw the proper exhumation of the human remains and the gravestones of the affected tombs were placed around the tree at that time, possibly to Hardy’s own instruction and design. Hardy later recalled this time in his 1882 poem ‘The Levelled Churchyard’, the text of which reveals his distress and anger at the sacrilege in which he was required to be complicit in the name of ‘progress’: “O passenger, pray list and catch Our sighs and piteous groans, Half stifled in this jumbled patch Of wrenched memorial stones! We late-lamented, resting here, Are mixed to human jam, And each to each exclaims in fear, 'I know not which I am!’” from ‘The Levelled Churchyard’ 1882 Over the years, the tree has grown through and between the gravestones, making a seemingly homogeneous structure, reminiscent of the tree-strangled temples of Angkor Wat. Whether or not Hardy knew, when he originally supervised the creation of this living sculpture in the heart of Victorian London, that it would come to stand as a symbol of his poetic vision is hard to say. However, when reading poems such as ‘Transformations’ or ‘Proud Songsters’, I find it impossible not to think of The Hardy Tree and wonder if it provided the seed from which they grew. I first came across ‘Transformations’ and ‘Proud Songsters’ when I was studying that other great poem of Hardy’s, namely ‘The Voice’, which was one of my set texts for GCSE. So fascinated was I by this poem that I can even recall phrases from the essays that I wrote about it. I remember getting a ‘Wow!’ in the margin from Miss Hulse for describing the rhythm of the first line as being ‘dry as a funeral drum’, for which I hereby belatedly apologise: I assume she didn’t notice that I had plagiarised this simile verbatim from Pink Floyd’s ‘One of My Turns’. (It had long been an earworm lyric for me, my Dad being in the habit of having ‘The Wall’ album on constant loop in the car on the way to school.) ‘The Voice’ sent me exploring further and - along with ‘The Convergence of the Twain’ and ‘Drummer Hodge’ - ‘Transformations’ and ‘Proud Songsters’ soon became and remain firm favourites. I rediscovered these poems again recently thanks to Alan Bennett’s beautiful 2014 anthology Six Poets: Hardy to Larkin. I wanted to share with my pupils why Hardy has had such a profound effect not only upon casual readers like me, but, as Bennett explains in his anthology, upon some of the greatest poets to have followed in his footsteps, Auden, Betjeman and Larkin to name but three of Bennett’s other subjects. We took ourselves into the garden at St John’s, where there happens to be a yew tree. Sadly not the dark, funereal presence that one imagines Hardy’s graveyard yew to be, our yew is rather more of a scrawny teenager hanging around beside the car park gate, as if eager to skulk off at the final bell. Far more promising is our willow tree. It stood tall in the middle of the garden for many a long year until, maybe five or six years ago, a wet summer and waterlogged earth saw it tip over under its own weight. Precariously propped up sixty degrees off the vertical by its lower branches, its fate seemed doomed. However, skilful tree surgery miraculously saved it and now it enjoys a second life as a living climbing frame-cum-Shakespeare stage. So, we wandered around the garden, reading ‘Transformations’ and ‘Proud Songsters’ as we went, taking turns to read lines in different locations, repeating them, discussing them, trying to reimagine them in this new context. Just as Hardy had tried to imagine where within his natural surroundings the souls and bodies of the departed had gone, I asked the children to think back not just within their own timescales, but in multiples of generations, to a time before the garden, the school, the buildings... What was here when our yew, our hollies or our willow put down their first roots? How many eyes have seen them over the decades and centuries? How many children have run around and between them? How many long-forgotten lives have contributed something to the energy that keeps these trees alive to this day? These were ideas that fascinated the children. All manner of questions arose from their discussions. If I dropped a tear or a droplet of blood on this spot and it seeped into the ground, would it end up being a part of that tree? Does that mean my DNA would be in the tree? How long would it take for all of the atoms in a body to become parts of other living things? All of these are the kinds of questions that Hardy is himself asking in ‘Transformations’ and ‘Proud Songsters’ and the fact that there are no definitive answers is what makes this such a rich seam for poetry. The children spent some time rough sketching and making notes on any observations that interested them within the garden. I wanted them to think deeply about all of the implications of Hardy’s words without feeling the need to launch directly into a response. They needed to work out what they thought, what particular questions and possibilities interested them. Then we left the thoughts to ferment. No attempts were made to write poetry on that first day. Over the following couple of weeks, the children started to use their notes and sketches to get writing. I gave them as little direction as possible, asking them only to show a progression from the beginning to the end of the poem: the ‘before’, ‘during’ and ‘after’ of their chosen transformation. As regards form, they were free either to emulate Hardy’s loose trimeter or to apply other techniques that they had practised elsewhere. Beth, for example, chose to use pentameter with great success: Transformations Blossom bloomed above you the summer when I left you under my grand cherry tree I can see your cheeks in the roses that Cover the garden you planted with me. When you died I planted in the garden A row of bluebells round your cherry grave In spring they grew into your bright blue eyes And your teardrops show in the river’s waves. Your toes came through the ground as spiked toadstools Trees twist far around you, smooth like your skin Swaying gently in the sharp icy breeze Nature around you shows the soul within. Beth, aged 12 I have mentioned her fourth line - “Cover the garden you planted with me” - previously in Chapter 4 and how this reminded me instantly of the dactyls in Hardy’s ‘The Voice’. Even though Beth had never read come across ‘The Voice’ herself, the coincidence did make me wonder if maybe there is some hidden quality of each individual poet’s voice - no pun intended - that moves undetected from one poem to another and resonates on the same frequency in the reader’s mind. Certainly, there seems to me to be something intangibly ‘Hardy-esque’ in Beth’s poem that goes deeper than the theme or the imagery and right to the heart Hardy’s poetic sensibility. Other children went in very different formal and stylistic directions, yet still managed to convey something of Hardy’s spirit in their poems, at least to my ears: Transformation It stood swaying in the wind Not like the willow Different from all Yet the same The bark frosted over Cold to the touch Its long sleep of winter had just begun Day after day it stood there Strong Waiting for a change As the ground changed around it As the years passed the school built around it And it knew what No one else was to know Tom, aged 13 Transformations He lies there His roots scarring the ground He looks over in envy at the children playing His playing days are over He remembers how it was to feel, touch and smell Now it is silent The children have gone Sap oozes out of his ancient bark He looks up at the sky It is littered with stars It is an icy evening The wind whistles The breeze bellows But all is still He wonders about his family Do they still think about me? Or am I a distant memory? Rory, aged 11 Will You Remember Me? Underneath the old apple tree I can still taste the dirt That I swallowed as I hit the floor I can still feel the stones That dug into my skin And so I fell Onto the cold ground And slowly I rotted away Abandoned, discarded, forgotten Rotting feels horrible I don’t recommend it And I fertilized the soil And slowly A sprout appeared Over the years that sprout Grew taller and taller Then it blossomed An apple tree My apple tree Tom, aged 11 Transformations Though life is fleeting, We live on. Though we may die, We live on. Though we may not Forever see the light, We live on. We: a cat, a dog, a frog; We live on. You: a rose, a bee, a tree; You live on. I: a man, an owl, a fowl; I live on. Seb, aged 12 During the writing process, we also looked at Harry Nilsson’s song ‘Think About Your Troubles’, taken from his 1971 philosophical album and animated film entitled ‘The Point!’ ‘Think About Your Troubles’ by Harry Nilsson Sit beside the breakfast table Think about your troubles Pour yourself a cup of tea And think about the bubbles You could take your teardrops And drop them in a teacup Take them down to the riverside And throw them over the side To be swept up by a current And taken to the ocean To be eaten by some fishes Who were eaten by some fishes And swallowed by a whale Who grew so old, he decomposed He died and left his body To the bottom of the ocean Now everybody knows That when a body decomposes The basic elements Are given back to the ocean And the sea does what it ought'a And soon there's salty water (Not too good for drinking) 'Cause it tastes just like a teardrop (So we run it through a filter) And it comes out from the faucet (And pours into a teapot) Which is just about to bubble Now Think about your troubles We discussed the meaning behind Nilsson’s song and to what extent his ‘Why worry?’ philosophy recycles Hardy’s idea and gives it a modern twist with which children can identify perhaps more easily. Inspired by this alternative take on Hardy’s idea, some adapted their ideas to go beyond the garden to other locations, such as rivers or oceans. A Tear Amongst these waves, There just might be, A washed-up tear, Belonging to me, Or between my toes, The crumbling sand, Perhaps slipped between The fingers of my hand, If it so happens, That from long ago, A tear Among the grass should grow Maybe if I go back, Someday soon, I could see a blossom, In full bloom Heather, aged 12 Transformations The river by my house Holds the lives of many. The tears that fall From family past Get picked up by the river blue. Another one cries in it too And that is how the river blue Holds a part of both me and you. Alie, aged 12 This exercise seemed to elicit from the children a genuine, deep understanding of the workings of the cosmos that invisibly operate all around, within and throughout our day-to-day lives. Nilsson’s film asks in a punningly literal manner whether everything must have a ‘point’, in other words, come to a definitive end. Can we not instead imagine ourselves as part of a cycle of ‘eternal return’? Would we not be ultimately happier if we were to do so? The children’s poems show a full engagement with this manner of thinking and an attempt to ‘work things out’ for themselves. In this sense, writing poetry can be a useful tool in allowing children to find a path through the labyrinth of life’s ‘big questions’. Luc Bat The democracy of the internet has over recent years allowed poetry to proliferate to the benefit of all writers and readers, professional and amateur. As a teacher, I never cease to be amazed at how often I can find out something entirely new to share with my pupils. The Vietnamese ‘Luc Bat’ form, for example, is one that I chanced upon quite by accident whilst browsing poetry blogs for good villanelles and triolets to use in lessons. (I later came across it again in Stephen Fry’s ‘The Ode Less Travelled’, where it is explained with wonderful clarity.) Not being a form that has been commandeered by any English-speaking poets of high standing, as far as I am aware, it occurred to me that this could be an excellent way of giving children a form to experiment with, with none of that intimidating sense of ‘standing on the shoulders of giants’. What’s more, the simplicity of the repeating six/eight syllable pattern to the lines - ‘Luc Bat’ meaning ‘six-eight’ in Vietnamese - gives children a clear structure to follow, which makes rapid progress possible. The only real complexity lies in how a Luc Bat rhymes, incorporating interwoven end and internal rhymes on the sixth and eighth beats. Here is an example written by one of my pupils together with a diagrammatic table to show how the rhyme works: The Circus I balance on the wire Each step I take inspires the crowd Below me. I’m a cloud Suspended in the proud blue air Reflected in the glare Dancers moving with care and grace Flickering thin blue lace Like glass dragonflies chasing fire. Edward, aged 13 The number of lines in a Luc Bat poem does not matter, which again makes it a brilliant form to use with children, who have the freedom to write as much or as little as they choose. As long as the poem finishes with an eight-syllable line which rhymes with the first line, then the poem is complete and true to its form. What happens in between the first and the last line is up to the writer, who only needs to keep the rhyme scheme going as indicated by my colour coding. (I usually explain it to children as looking on the page rather like knight moves in chess, which can be helpful to those with a visual learning style.) To assist the planning stage, I give the children their own grids to play with, either on paper or digitally in the form of spreadsheets, like this: They always enjoy messing around with their colour coding and the fact that they can fill it in for as long as they want to gives them the motivation to keep adding, removing and editing as they go, thinking about their rhymes all the time in order to keep it going. In this sense, writing Luc Bat has something of the enjoyment and spontaneity of engaging in rap battles and it therefore works particularly well as a paired activity, with the children batting words, phrases or whole lines back and forth to each other, using their grids as a guide for the rhyme patterns and syllable count. The following poem was written in this way, with Adam and Roddy going to ever greater lengths to ‘out-mad’ each other’s ideas in a kind of surreal word association game: Luc Bat of Insanity I hate feeling this way Stooping images sway. Unsure How the sky is: azure Or red in tone so pure. The scream Pierces my widening dream Magnifying light beams, knick-knack Makes me want a Tic-Tac Vendor sells bric-a-brac, it clots My head with polka dots Cluttered dreams, shattered pots, death’s choir Claims my five-year-old fire Bad dad (funeral pyre). Pipers, ‘Death to windscreen wipers’ Kill me with a sniper. My way. Roddy and Adam (aged 12) As can be seen in this example, the Luc Bat form can foster a highly original way of writing that is reminiscent of the automatic writing with which the early Surrealists experimented. Paradoxically, the limits placed upon the choice of useable words by the rhyme scheme and the need to carefully count syllables allow the writer to make rapid progress. With the assistance of a rhyming dictionary, particularly an online one such as RhymeZone, the young writer can explore the various possibilities of word choice and, when these are limited to just one or two options, this can then dictate the direction in which the poem must go. The end result reads almost as if the poem has ‘written itself’ and thereby gained a life of its own.  ‘Villanelle’ by Sondra Ball Another form of poetry that is traditionally taken to be difficult, and therefore ‘not for children’ is the villanelle. Originating in Italy in the sixteenth century, it is a ‘closed’ form consisting of only two rhymes and repeating lines which follow a fixed pattern. There are five tercets (three-line stanzas) and a final quatrain (four-line stanza). Each tercet follows the rhyme scheme ABA, whilst the quatrain must take an ABAA scheme. Within these limitations, there is the further requirement that specific lines must be exact (or close) repetitions of each other. Lines 1, 6, 12 and 18 match; lines 3, 9, 15 and 19 do likewise. As with the triolet, the easiest way to grasp this pattern is to see it laid out diagrammatically: The lines left blank are all different and must only rhyme as per the given rhyme scheme. There are no fixed rules as to length or metre for any of the lines. When applied this scheme is mapped onto to Sondra Ball’s villanelle, the pattern becomes clear. As a teenager, I first discovered perhaps the best known villanelle in the English language: ‘Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night’ by Dylan Thomas I remember being taken by the haunting nature of the repetition and the power that built up through the course of the poem, the lines carrying more passion and meaning with each repetition. As with the Shakespearean sonnet, I did not know at the time that this poem’s form had a name and a history, assuming that Thomas had devised the structure himself. Only through chance discoveries of other villanelles, such as Elizabeth Bishop’s ‘One Art’ and W H Auden’s ‘If I Could Tell You’, did I recognise the familiar form and make further inquiries. When eventually I came across Ball’s beautifully self-referential ‘Villanelle’ a couple of years ago, I started to wonder about the possibility of using it with children. The first stage with teaching closed forms like this is, for me, always to write one or two of my own, just to be sure that I am not barking up the wrong tree. (Perhaps these villanelles really are as difficult as they are cracked up to be, so letting children loose on them could well prove to be torture for all concerned... ) However, the beauty of having a go at a poem in a closed form is that you at least know before you get going as to what you are trying to do and how your end result should end up. To revisit my previous cookery analogy, having a kitchen full of ingredients and no idea as to what you are trying to make is going to be a hit-and-miss affair at best. Knowing that you are trying to make a Coffee and Walnut cake, on the other hand, at least tells you that the tabasco sauce, the anchovies and the Oxo cubes needn’t be even taken out of the cupboard, let alone experimented with. Here’s what I came up with after half an hour or so of messing about: Villanelle The clock’s slow ticks. Your heart’s dry beat. The telephone waits, indifferently dumb, And endlessly the days and nights repeat. Footsteps thump from the frozen street, Fade to air like a passing drum. “The clock’s slow,” ticks your heart’s dry beat. The fire gives off an unfelt heat, The radio, a half-heard hum, And endlessly the days and nights repeat. One by one your hopes retreat, As shadows on the floor become The clock’s slow tick, your heart’s dry beat. Pages snowdrift at your feet. You stare them through, unreading, numb, And endlessly. The days and nights repeat Until their sameness is complete And now you know I will not come. The clocks, slow, tick your heart’s dry beat And, endlessly, the days and nights. (Repeat.) Ashley Smith The previous week I had been looking at Wilfred Owen’s ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ with my Year 8s as part of our studies of Remembrance Day. I think this is how the idea of the woman gripped by the agony of waiting for news of a loved one first emerged. It is interesting, however, that I did not consciously set out to use that particular idea. Instead, I simply started with the image of a clock and tried to turn that into a line that had the flexibility to have different meanings, in spite of needing to be repeated four times: The clock’s slow ticks. Your heart’s dry beat. “The clock’s slow,” ticks your heart’s dry beat. The clock’s slow tick, your heart’s dry beat. The clocks, slow, tick your heart’s dry beat As well as being enjoyable to generate, this kind of word play has obvious value in the teaching of parts of speech, syntax, grammar and punctuation, and, having designed this to be a ‘teaching’ poem, I was pleased to see how responsive the children were to the nuances of meaning offered by, for example, the presence or absence of an apostrophe: the clocks (plural noun); the clock’s (‘the clock is...’); the clock’s (‘of the clock’). They were also quick to spot how the heart is personified by the introduction of speech marks - “The clock’s slow,” ticks your heart’s dry beat. - and had some lively discussion as the difference in effect between the full stop and the comma working as caesuras in the otherwise identical lines: The clock’s slow ticks. Your heart’s dry beat. The clock’s slow tick, your heart’s dry beat. Some felt that there was no tangible difference. Others thought that the full stop in the middle of the very first line makes the woman seem calm and patient early on, with the later use of the comma suggesting a mind become more agitated and frantic, increasingly driven mad by the clock. These were observations which had not occurred to me whilst writing the poem; I had merely wanted to experiment with using different punctuation as a writer, rather than analyse it with the mind of a close reader. One child suggested that ‘tick’ in the final couplet could be read in the sense of ‘mark’ (i.e. ‘tick off’) as opposed to the sound sense used elsewhere. This, again, hadn’t crossed my mind in the writing process, but I now find that I agree with him and it helps to salvage an otherwise rather clumsy ending. By discussing the process of writing my own villanelle with the children, I was able to develop a greater understanding of the best way to go about it. Whereas I had started with my first line and worked on from there, in fact, it would have been a whole lot easier and more logical to start with the final couplet and work backwards. The final couplet, in that it contains both of the repeating refrains and in that it needs to make sense when the two refrains are juxtaposed, is the key to making the whole poem hang together properly. Daniel, aged 13, clearly understood this and spent more time grappling with his final couplet - Over the sheer cliffs the black bird flies, Under the stormy skies the murky water lies. - than he did with the remainder of his poem, which fell into place for him quite easily when he used a rhyming dictionary to whittle down his two rhymes to a bank of usable words. With these at his disposal, all he then needed to do was to map them onto his ‘villanelle grid’ and use them to anchor the narrative of his poem. The end result is certainly intriguing and shows the curious power of the villanelle to get children writing with haunting potency. Villanelle Over the sheer cliffs the black bird flies, Searching for a place to land Under the stormy skies. The murky water lies Under the cliffs as the black bird tries To find a home on the sand. Over the sheer cliffs the black bird flies. From far away you can hear its cries, You can look towards the sea so bland, Under the stormy skies the murky water lies. Endlessly the ocean will rise, But never will that bird lose heart and Over the sheer cliffs the black bird flies. Although this bird has never been seen by eyes, School children are still told the legend: "Under the stormy skies the murky water lies." So ever if you stand under these skies, Remember my command: "Over the sheer cliffs the black bird flies, Under the stormy skies the murky water lies." Daniel, aged 13 |

AuthorSixteen years of teaching poetry to children have furnished me with a wealth of ideas. Do dip in and adapt any of these for your own lessons. Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed