|

‘Not The Furniture Game’ by Simon Armitage

With another class, Luke Wright gave a reading of Simon Armitage’s ‘Not the Furniture Game’, in which a barrage of metaphors describe the poem’s protagonist from head to toe, all building up to a shocking climax when the focus shifts to a woman, described as a ‘chair tipped over backwards’ in an allusion to the poem’s title, who has, we suppose, been attacked or even murdered by her larger-than-life partner. This was certainly not the kind of poem that one might typically expect Year 7 children to be grappling with, but they responded with incredible maturity and insight, using the regularity of the structure together with the openness of the metaphorical possibilities to make profound statements about things that matter to them. The standout response was by Charlie, an unassuming Year 7 boy, who had never shown any particular inclination towards poetry and had previously struggled to find a voice in his creative writing in general. Requiring no further external input or assistance, he quietly got on with writing this: Dad His hair was icebergs clashing together His eyes were whirlpools pulling in ships And his bite was blacksmiths smashing steel His neck was a spear And his shoulders were tree trunks in the autumn His handshake was fire His elbows were knives blunted His shadow was a cumulonimbus His legs were steel doors His feet were bells ringing with every step His fingers were snipers His footprints were maps And his heart was a bus We were the sword that cut through his cancer. Charlie, aged 12 When we convened in the school hall for the final hour of Luke’s visit, during which the children were given the opportunity to read their poems aloud to the rest of the school, this was the one poem that stopped everyone in their tracks, pupils and teachers alike. I think it stands as proof of the cathartic effect of poetry on children, allowing them to access and publicly express emotions which they might otherwise be embarrassed or unwilling to share. Poetry, in common with other art forms, creates a protective bubble around its creator, letting them explore that which might be too challenging or awkward in the literal world. It enables them to revisit, dissect and rebuild complex memories in an effort both to discover the truth behind them and to render them more manageable. Seeing his words wield such power over an audience demonstrated to Charlie that this is a great poem. Entirely at his own initiative, he decided to enter ‘Dad’ for the 2015 Hippocrates Young Poets Award and was awarded an honorable mention by the judges. There can be no better proof that children have at their disposal, within their own memories, the material to convey a message that is relevant and profoundly meaningful to anyone and everyone. All that we, as teachers, need to do is to give them the means of sharing these memories.

0 Comments

‘The Sea’ by James Reeves The simplicity of James Reeves’ opening line of ‘The Sea’ is what makes this a particularly useful poem for teaching children about the power of metaphor. The poem almost seems to write itself after this basic premise, with the young reader’s mind already primed and excited to embark on the journey aboard Reeves’ train of thought. Indeed, this is one of the many poems that I have used with which the first 15 minutes of the lesson are often happily and productively spent bouncing around the implications of this initial line: Do you agree? Why? Why not? In what way is the sea a ‘hungry dog’? What does it do? Why does it do it? etc. The questions arise quite naturally and the children - whatever their age - always respond with plenty of creative and original ideas, prior to ever seeing anything other than Reeves’ opening line. Perhaps this comes down in part to its vocabulary, which is accessible to all and therefore linguistically unthreatening. I would argue, however, that the primary reason why this opening line hooks the young poet is that there is an innate openness to metaphor in most, if not all, children. The very use of the metaphorical ‘is’ as opposed to the simile-generating structure ‘is like’ immediately challenges the child to think more deeply and, in doing so, they are quick to tap into the noises, smells, colours and shapes of the sea that make the dog comparison resonate. When they then look at Reeves’ actual lines, children are quick to notice the long, low sounds of the sea echoed in the long vowel sounds - ‘rolls’, ‘hour upon hour’, ‘howls’ - and the irregular but insistent rhyme scheme - ‘bones/stones/moans’, ‘jaws/gnaws/paws/roars/shores/snores, ‘sniffs/cliffs’ - that evokes the varying rhythms of the waves. Assonance, alliteration and onomatopoeia play central roles in conveying the sounds of the sea in this poem and valuable time can be spent not merely in identifying where these are within the poem but what exact effects they are creating. I recall one Year 5 child mentioning that the lines - “And 'Bones, bones, bones, bones! ' The giant sea-dog moans”

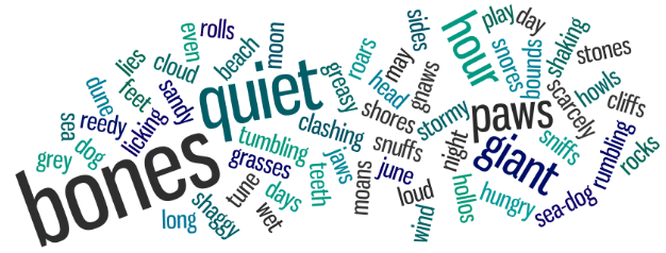

The Forest The forest is a lonely cow Lumbering and brown. She swishes, swishes the sky all night. With her smooth teeth and slow jaws Hour upon hour she chews The echoing, dark trees, And lows, lows, lows, lows! The lumbering forest-cow lows, Standing stock still On her huge tree-trunk legs. And when the morning wind is hollow And the sun sways in the windy day, She stays on her feet and rustles and chews, Shaking her fleas, wanting peace, She groans and moans long and slow. Ingo, aged 10 Much of what makes ‘The Sea’ such a memorable poem comes down to the clever use of repetition and rhyme, so as to provide a constant reminder of the recurrent sounds of the seascape. As Ingo has done in his forest poem, finding ways of conveying the sounds of a place through combinations of onomatopoeia, alliteration and assonance (‘swishes, swishes the sky all night’/’lows, lows, lows, lows’/’She groans and moans long and slow’) really appeals to the child’s innate fascination with words as playthings to be put together rather like Lego bricks to create colourful, crazy structures, as opposed to using them simply to string together units of meaning. Like Reeves, Ingo has ‘built’ his forest metaphor from a montage of interesting sounds and images, allowing him not to get bogged down with literal interpretation. To further facilitate children with tapping into this technique, a very useful app to consider using is www.EdWordle.net Insert any text into it and you can instantly create a ‘word cloud’ of it, in which the more often a word occurs, the larger it will appear. Here is a word cloud of ‘The Sea’ with common words (e.g. ‘the’, ‘and’, ‘but’) removed: Word clouds such as these can be used to introduce a poem, in this case, for example, by asking the children to make suggestions as to what the poem represented by it might be about. The prominence of ‘bones’ and ‘paws’ might well lead the children to identify the dog theme fairly quickly; those who then look more closely to find ‘cliffs’, ‘sandy’ and ‘beach’, for example, will start to ask themselves questions. Is this a poem about a dog running around on a beach, maybe? Already, the images of ‘dog’ and ‘sea’ will be brought together in the child’s mind and everyone can set to work on spotting patterns - rhymes, onomatopoeia, alliterative pairs - still without having to worry about the ‘meaning’ of the text itself. In this way, you will be able to have the children engaged in discussing ideas and playing with words, such that once you start looking at the poem itself, they are ‘warmed up’ and ready to start writing in a similar way: The Dark The dark is a dragon Big and black He roars like a lion With a crunching jaw Fierce face All through the night he watches and waits In his sleepy cave Until in rage he awakes He roars and rumbles And breathes blazing fire Into the dawn of the day Tom, aged 10 Winter The winter is a snarling wolf, Biting the ones who disturb it, Rewarding the one who serve it, With cold refreshing snow. But on a warm winter's day, He cowers as the acidic heat, Burns into his body, Ow, ow, ooow! he cries. But on cold days of December, He crosses his domain, Spreading like ice, Howling, howling all the time. And as the winter ends, His eyes shine with sadness, And he slinks down and down, To places men will never go. Ben, aged 10 The Snow Hippo The hippo is a raging winter. Its teeth are splinters, The snow growing over time, Eventually ‘gone’. It is all mine. The size is overwhelming Swelling with snow. It will pounce only if annoyed, The wind moving it all the time. No void can move it, Only heat can. Hugh, aged 10 A Volcano A volcano is like a hungry cobra Vicious and violent He lies watchful, waiting to strike. Tom, aged 9 The Night The night is a lion’s jaw Shutting like a door slammed loudly. Wham! And you can’t see a thing. The night plays tricks on you Like a lion: Quickly. Jim, aged 10 The Eagle The eagle is pure gold. With his great and glimmering beak He soars over the mountains at midday. At night he sledges down the white snow In a blaze of shining light Like a king on his golden toboggan. William, aged 10 (SATIPS Poetry Competition 2011, Highly Commended) One longstanding favourite activity of mine which was inspired by ‘The Sea’ and which has worked particularly well with children at the younger end of the age range is the ‘randomizer’ method of metaphor/simile building. For this, I use tactile objects such as ping-pong balls, which help to make the activity seem like more of a ‘game’ than a ‘lesson’ in the traditional sense. The children simply take a ball from each of three boxes. The thirty or so balls in the first box have random concrete and abstract nouns in the singular form written on them, e.g. ‘rain’, ‘joy’, ‘life’, ‘summer’ etc. The five or six balls in the middle box have either ‘is’ or ‘is like’ written on them. In the third box, there are again thirty or so nouns, often together with a modifier, as per what will work grammatically, e.g. ‘a hurricane’, ‘the ocean’, ‘my bedroom’, ‘candyfloss’. By selecting their three balls at random, the children are given a ready-made simile or metaphor to use as a starting point and to develop in their own way. Often their selection will not make immediate sense and there will often be fits of laughter and protests along the lines of: “Rain is like my bedroom! That’s just silly!” However, with a little encouragement not to reject their selection in favour of a new one, but rather to take the idea away and play with it in rough for a few minutes, there can often be some astonishing results: Happiness My happiness is a child Rushing home to tea Sorrow My sorrow is rain Falling steadily in the night Fear My fear is a sprawling spider Creeping silently behind the enemy Prepared to pounce Breath held Fangs exposed The venom seeps into the withered veins Ollie, aged 9 What is the Sun? The sun is a giant Yorkshire pudding Served piping hot It is a glinting pendulum Dazzling our eyes The sun is a fishing hook Lowered down and down Then hauled back up again But it never catches anything The sun is a large luminous eye Watching over the universe It is a discus Flung from the depths of the deep black sky Benedict, aged 9 What is a River? The river is a blue fist Pounding through the mountains It is a whipping rope Lashing out to sea The river is a deadly blade Slashing countries in half It is a dying man’s lifesaver Glistening in the sun Henry, aged 9 Similes Love is like an avalanche, It builds for years and falls in minutes. Boredom is like a stone, It never changes. Frustration is like the ocean, It shows you knowledge and yet you’re never satisfied. The future is like a candle, But the wick is still to be lit. Joy is like a lighthouse, It shines when needed. Thomas, aged 10 Thoughts A thought is like a story; you never know where it will end. Jealousy is like a flame; it spreads and engulfs your mind. Desire is like ice cream; the more you have the more you want. Frustration is like a star; when it collapses, it sucks you in. The past is a winding road; it spirals around you and makes you who you are. Sebastian, aged 9 (SATIPS Poetry Competition 2013, Years 5 & 6 Winner) Time The future is like ice. You never know when it might break. You might slip and fall, You could stand tall and proud. Beneath the ice hidden secrets could be lurking in the depths. The present is like water. It flows freely and explores. It makes its way through storms of hardship And flows through the clear sky of happiness. The past is like steam. One second it is the water so clear, The next it has turned into thin air, Lost from sight. Emma, aged 10 These poems were written by children across the full ability range, and, as can be seen, each one has its own particular merits in terms of extending the metaphors and similes such that a seemingly inapposite comparison becomes meaningful through deeper exploration. The children were encouraged to really delve into how one randomly selected noun could be compared in some way to another, however difficult that task may seem at first glance. Repeatedly asking themselves how or why X ‘is’ or ‘is like’ Y gave them a model by which to extend their ideas to full effect. By approaching the exercise as a playful philosophical challenge, the writers were all the more driven to come up with original thoughts and, without any need to labour the explanation of metaphors and similes, they got straight to the intended business of creating them for themselves. They were allowed to work on numerous discrete ideas, returning several times to select new ping pong balls; alternatively, as Emma did, they could start with a single comparison (in this case, ‘future’ = ’ice’) and then extrapolate their own equivalents from it (‘present = ‘water’ and ‘past’ = ‘steam’). As I have suggested previously, there is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ way where children’s writing of poetry is concerned; having the flexibility to allow the children to go off in their own direction from a common starting point or towards an agreed goal should always prove successful and pleasurable for all concerned. What particularly interests me about the poems produced by the children engaged in this activity is how clearly one can detect the preferred modus operandi of the child in the finished piece. Those children with more of an impulsive learning style, will tend to be those whose work shows a colourful array of disparate and often unconnected images, which can create startling and exciting juxtapositions. Those children, on the other hand, who like to think through one idea slowly and thoroughly before moving on to another will tend to produce a more measured and coherent composition, going deeper into the underlying meanings. Neither end result is ‘better’ than the other, in my opinion. Indeed, the joy for me as a reader of poems written by children attending the same lesson lies primarily in the often striking differences that emerge between them.  ‘Mirror’ by Sylvia Plath Notwithstanding the occasional appearance of poems such as ‘Mushrooms’, ‘You’re’ and ‘Metaphors’ in poetry anthologies for younger readers, Sylvia Plath is a poet who would rarely be mentioned in the same breath as the phrase ‘children’s poetry’. However, as with my earlier examples of Philip Larkin and U A Fanthorpe, I am always willing to use a poem by a writer of abstraction and complexity such as Plath, provided that the underlying ideas are ones with which children can identify. (Even if the language is in parts obscure, all children will be able to handle the general thrust of a ‘difficult’ poem, provided sufficient time is given to class discussion.) ‘Mirror’ is a poem that goes back a long way for me, it having featured in the anthology that formed part of my GCSE studies, namely Touched with Fire, edited by Jack Hydes. It would never have occurred to me to use it with children if, on starting my first teaching job in 2000, I hadn’t rifled through all of my old school folders and found these, written when I was in Year 9: Meeting I turn on the taps And the steam hides my friend Behind a misty opaque window Of smoke. The only way I can bring him back Is to slap him And to smear my fingers across His cold and shapeless face. So why doesn’t he go away Or even slap me back? His glossy eyes give an icy stare And his smile is faked. His red face is washed And his hair combed into strange contortions Until we are complete. Then we depart from the strange window, To return some other time That we both know, But without a word spoken Between us. Mirror World The clocks go back in time and lights Stand upright from the peeling plastered floor Like lamp posts. Mirrors reflect Mirrors within Mirrors; An eternal row of military images which vanish Into the distance. The room revolves, Crashing ghostly figures into each other unawares. The room is like a house of cards Where Kings meet Queens in the middle But face away. Siamese Jacks, silently bisected and sewn together In sudden operations. In this mad world The boys wear blouses and the girls wear shirts. Extra-limbed aliens walk around as if human. We read in a foreign alphabet And write wrong-handed. Then the mirror moves And the House of Cards comes tumbling down. And so the memory was triggered. I had written these for my school’s annual poetry competition. Mrs Swigg, my English teacher at the time, had ventured over to the Science labs to borrow a box of the mirrors that they would use for the light reflection experiments in Physics lessons. For homework, we were to take two of the mirrors each and walk around at home or outdoors, observing the different effects that can be created by looking at the world with them. A mirror in front of one eye but not the other. A mirror slightly bent or twisted. One mirror placed at right angles to the other. I had spent a good hour driving my mother mad by walking around the house bumping into things and knocking antiques off tables, so absorbed had I been in this activity. And then, for the rest of the evening, I had drafted and redrafted ‘Meeting’ until I was happy with it. Next day, aware that the rules of the competition allowed everyone to enter two poems, I spent all of double Latin secretly holding the mirrors behind my textbook and reflecting them off the ceiling and a pack of cards that I had to hand (The card game ‘Spit’ was the big craze at the time.) By the end of the lesson, ‘Mirror World’ was finished and I thought I’d throw it into the mix as well, even though I thought ‘Meeting’ was the better poem, because I’d done that one ‘seriously’. However, to my amazement, it was ‘Mirror World’ that Mr Cash, Head of English, preferred and there I was, ‘Highly Commended’ for something I had written in fits and starts in the middle of trying to translate something about slaves and fields from our Latin textbook, Ecce Romani. What intrigued me on discovering these poems is that, without referring directly to Plath’s ‘Mirror’, my teacher had managed to get her pupils thinking like Plath, engaging with the world directly, physically and in a totally new way in order to write. When studying the Plath for GCSE, it had not occurred to me to look back at my own mirror poems and compare them, never thinking for a moment that they had anything to do with each other. After all, Sylvia Plath was a ‘proper’ poet and I was just someone who liked to show off with big words. However, looking back over my own writing at the start of my teaching career, I realised that, wherever my words came from, however good, bad or just cringeworthy they might seem now after ten years shoved in the bottom drawer, they paint a picture of who I was then and might be used to help my pupils put something of themselves into words. It occurred to me that, by showing children how one of the greatest poets of all time used the theme of the mirror and that anyone can create their own original response to the same theme, this might encourage them to give it a go themselves. So here is the task that I gave them: Read these two poems (‘Meeting’ and ‘Mirror World’,) together with Sylvia Plath’s ‘Mirror’. Then, use the mirror provided to spend a few minutes looking at the world around you.

Note down any ideas that occur to you in rough. Now, plan your own poem inspired by the theme of looking in (a) mirror(s). Don’t forget to think of the various different types of mirror that are used in everyday life. Remember that the poem does not have to rhyme if you do not wish it to. I didn’t tell them who had written the first two poems until we had read and discussed them together. This gave them the freedom to criticise and compare freely, without any fear that they would offend me with their opinions. Their observations were fascinating. They spotted things in my poems that I had not - pleasing and less pleasing word choices, unintentional alliteration, awkward syntax, interesting line breaks - and treated all three poems as equals. The name ‘Sylvia Plath’ does not, of course, resonate any more strongly in a typical child’s mind than ‘Anonymous’, so their analysis was not distorted by preconceptions (just like Plath’s own mirror). On telling the children - it was a class of Year 7 pupils on the first occasion that I did this activity - that I had written the two anonymous poems when I was fourteen, I could sense the atmosphere sharpen. I was half expecting them to say, ‘Oh, well they’re not proper poems then, are they?’ and feel somehow duped. Far from it. The instant response was along the lines of: ‘Right, I’m going to do that!’ and off they went: Mirror World As I stare at the mirror It stares back at me Its skin as pale as gruel. When you think of the world Inside a mirror You think of it Ever so cruel. Words have no meaning, Beginning is end, Paintings hang upside-down on the wall, Trees all grow downwards, Heaven lies in the earth, And aeroplanes begin softly to fall. Angus, aged 12 Reflection He is always there In every mirror, Distorted in each piece of cutlery, Faded, faceless, in every pane of glass Ready to replace me If I laugh, he copies A cold humourless clone He is only truthful But it is a half truth I almost have pity For one trapped in A cold, dark reflection. Aaron, aged 12 A Reflection I am the mirror on the wall With ornate frame of gold And strange temptations like a siren’s call To bend you to my careful mould There is no choice For me nor you I simply do what I was made to do You made me, took the decision To see yourselves backwards Tom, aged 12 Rain Mirror It forms as the rains come; Gathers when a myriad droplets Crash, exploding, to the dry ground. Slowly it seeps from the centre, Expanding, growing, covering the road With its silvery surface of reflection. Then the rains stop. The mirror stills, shines Its information brighter. The eye sees deeper, finding Changing pictures now Glimpses of a foreign world. And as the eye begins to marvel Drawn closer to this simple pool, A single stone, source unknown, Approaches, growing faster, gaining speed, Until, with a silent explosion, The world of the mirror shatters Into a thousand liquid shards. Paris, aged 11 The Mirror I am pinned to the wall and hang there, Thinking, reflecting, Watching, waiting, for something to happen For someone to come past, something to see So then they can see too. I bring disappointment, rarely joy, But cannot help it. It is strange how they are never satisfied. I seldom see a single soul that smiles. People pass, frowning and sighing And always come back, to sigh once more. Alex, aged 11 The Mirror Smashed, stained, abandoned, Lying in the attic covered in cobwebs, Unable to make a sound, Waiting, waiting Like an idea trying to come back to life, Hearing, hearing Only the occasional murmur and running On the downstairs corridor. Sometimes, sometimes Having hope, When a fine light shines on its face And then dimming. The sound of talking Echoing around the room like a cave And at night Hearing nothing, nothing But the sound of the cars And flashing light Streaming through the window. Grace, aged 11 Dancing in Anger I watch her twirl. Savagely tearing a hole In her world. She Becomes a blur of colour, Of light. I watch her stretch, Viciously creating line after Line through her hands, Her elbows, her shoulders. She is dangerous. I watch her bow. Her emotions still outside Her control, her body. She shakes and trembles. I watch her leave. She sends the studio Into darkness. I cannot Reflect anything now. Surely there is nothing there? Anna, aged 11 (Foyle’s Young Poets 2011, Highly Commended) This is just a small selection of what the children produced as a result of this session. All of them were given the opportunity to develop their ideas gradually over time, drafting and redrafting them electronically, in order to ease the process of perfecting the finished result. The ever-increasing use of IT in the educational environment is of enormous advantage to the creative process where writing is concerned. I always encourage the children to move electronic copies of their work over to shared folders as soon as possible, even if it is only in the initial stages of development. That way, they can seek advice not only from me but from all of their peers, as to which images and ideas work well, whether or not they should stick with the rhyme scheme that they have chosen, how they should bring their poem to a satisfying conclusion, and so on. Children respond very positively in my experience to this very open approach to writing poetry, and seeing each other’s work develop organically, far from encouraging ‘copying’, seems to elicit the very opposite, i.e. a desire to plough their own furrow and come up with something truly unique. As we discovered through the Mirror Poems activity, using a common thematic starting point and taking time to revisit the work in progress at regular intervals over several weeks produced a very interesting and varied collection of poems which sought to explore forms, influences and approaches in novel ways.  There can be little argument that great poetry relies on the original use of figurative language. Getting the idea across to children as to what we mean by figurative language can, however, be easier said than done. No list of dictionary definitions of similes, metaphors, personification etc. is going to be as effective as regular and meaningful engagement with figures of speech in their natural environment, doing their magic as their creator intended. Isn’t it curious, then, that many teachers waste time trying to explain to children what a metaphor is before actually bringing them into contact with one? After all, one would not content oneself with explaining to an alien what an elephant is if one could just as easily take him outside and show him one in the flesh. I speak partly from personal experience here. The first time I had ever heard the word ‘metaphor’ was in a Year 7 English lesson, in which the teacher dictated to the class to copy down in the back of our exercise books: “A metaphor is when somebody calls one thing something that is not really, for example: ‘the moon’s a balloon’.” (It’s still there, in royal blue washable ink, carbon-dated to 1987 by the weird, uncrossed ‘f’ I was experimenting with at the time in an attempt to achieve fully joined-up handwriting.) And then we moved on. No further mention of metaphors came up until the end of term test, in which the question “Give an example of a metaphor” appeared. I could have taken the easy way out and just written “The moon’s a balloon”, but I wanted to have a go at coming up with one of my own. Drawing on the ‘moon’s a balloon’ idea, which to me sounded quite jovial, I remember deciding that a metaphor had to be humorous or ironic in some way. So this is what I came up with: “My sister is a junior Avon lady on Saturdays”. Yes, indeed. That was my first attempt at a metaphor. I, of course, knew what I meant. I was trying to convey the idea of a sister who wears too much make-up (which to me was doubly ironic, as my actual sister would never have touched make-up with a barge pole, being more likely to be smeared in horse manure of a typical Saturday). So, knowing that Avon ladies spent their lives surrounded by cosmetics, the ‘metaphor’ seemed to tick the box: “A metaphor is when somebody calls one thing something that is not really”. Of course, the test came back with a big fat cross next to my metaphor, tainting an otherwise perfect score. “OK,” I thought. “I can do everything else but I’m rubbish at metaphors.” What I couldn’t understand was why. Hadn’t I done exactly what the definition was telling me to do? Unfortunately, I never had the courage to ask where I had gone wrong, or rather, what I had not managed to get ‘right’ with my metaphor. Metaphors did not crop up again for another year or two, by which time I was ready for them and could grasp what the writer is trying to do when using them, i.e. to convey a comparison that may not have ever occurred to the reader, but which will resonate and enrich the image and the understanding of the things being compared. As a child, I was always very literal in my use of and approach to language, preferring information conveyed factually to ideas expressed figuratively. I would always pick up an atlas, for example, in preference to Enid Blyton or a guide to dinosaurs in preference to a poetry anthology. I see similar traits in many pupils that I have taught over the years, especially boys, and so, I can fully empathise with the difficulty that they will inevitably have when asked to recognise, respond to and recreate figurative language. Children very often just want to say it how it is and struggle to think outside of that box. “Why would I want to say that a cloud is (like) a ship, when it’s not a ship? It’s just a cloud!” goes the thinking. To get children confident and enthusiastic enough to make this leap of faith and imagination, the key is to immerse them as much as possible in examples in context and to let them engage in playful experiments. No child dislikes being given a free rein to play, and this applies as much to the world of words as it does to the world of, say, football. ‘The Apple’s Song’ by Edwin Morgan A great way to introduce this poem is simply to omit the title. As the text of poem itself does not contain the word ‘apple’, the teacher can instantly spark the interest of the children by asking them to work out who the ‘I’ of the poem is. Most children, of course, will work it out very quickly, when they hear the verb ‘peel’, for example, but just giving them that initial incentive to listen/read closely as part of a guessing game will get them immersed straight away into the conceit created by Morgan’s extended metaphor. If, as is likely, the children have correctly guessed that the speaker of the poem is an apple, another step might be to ask them to guess the title of the poem instead of telling them directly. Again, giving them the freedom to share ideas and justify them will get your pupils thinking deeply about why the poet has chosen to make an apple speak and the ways in which he has cleverly enabled the listener to suspend disbelief and see into the ‘mind’ of the apple. One can then move on to ask questions about why the poet thinks of this as a ‘song’, about what the apple wants to achieve by ‘singing’ it and so on. Even your most literal-thinking pupils should be able to open their minds to this game and, before long, you should be able to get them writing similarly interesting ideas, either emulating the personification of the original or developing a perspective of their own: Apple As the knife plunges The apple’s crunch Sings a song Edward, aged 11 The Apple The hard shiny armour glistening in the light The crunching of the shield breaking under my teeth The smell of blood dripping on the floor The luscious taste of the inner body The black heart hitting my teeth The skeleton being chucked away Tom, aged 11 Apple I hold the apple in the palm of my hand, I watch the dense colours mingle, I run my fingers down the incline to the heart, I raise the apple to my watering mouth, I dig my teeth into the skin and flesh, I hear the crunch, like shockwaves, through the apple, The unmistakable taste washes through me, A wave from the sour sea. Lucy, aged 11 Apple Like a garden after rain Fresh, sweet The apple pips rest In the soft white flesh Of the heart Isabel, aged 11 ‘The Apple’s Song’ can provide an excellent springboard not only for ‘apple’ poems like these, but for all manner of metaphorical experiments in which the children imagine themselves as inanimate objects. Here is the text of a follow-up activity to this poem which produced some excellent results from children of various ages and levels of ability: Think of an object. It can be a natural object, such as a banana, a flower or a grain of sand. Or it can be a man-made object, such as a pencil, a tennis racket or a violin. It can be a small object in your pencil case, or a bigger object, such as the door or a chair. Now try to imagine what the object would say to you if it could speak and you have the makings of a brilliant poem! Before writing anything down, consider these questions: What kind of voice would the object have? What character / personality? Where does the object spend most or all of its time? What would it be bursting to say, if it could speak? Is it good, or is it evil? Is it happy, or sad, joyful or tragic? Would it be positive, or would it moan about its place in the world, or criticise? Now try to write down what your object would say. I allowed the children to choose whether to tackle the questions individually, working through them like a questionnaire and writing their own rough notes, or to work in pairs to ask the questions interview-style. Permitting different approaches like this in the targeting of a common goal always makes for a happy and productive poetry classroom, with the children being able to play to their own strengths and personalities. The more vocal ones will love being able to discuss the questions with each other, bouncing ideas around which will inform their own individual writing, whilst the children who prefer to work alone will be able to engage straight away in a private internal dialogue with the questions on the page. Both approaches can be equally effective and rewarding, and we all have our own preferred learning styles, so allowing them to co-exist in the same context is always going to make for a successful lesson. This idea has worked similarly well with children in Years 3 through to 8 and there is no reason not to give it a go with children above or below these ages. Here is just a small selection of the work produced by my pupils: Scissors I glide through paper Running, beak snapping Fledgling pattern maker Idea shaper Metal snipper Dancing legs Separating splits on the attack. Eloise, aged 8 Rock I am swirled and twirled by the cold wet sea I am thrashed and washed by the wild water The years roll past and I roll from continent to continent I see dolphins leap over me like arrows I travel from hot to cold and around the globe I am caught in nets and dropped Pushed and pulled by the sea Tossed onto the beach And found by a small child. Charles, aged 8 Silver I am the moon rock, The swan’s eggs, The birch wood. They pick me out, Smashing at me till I crumble. My knees buckle, I fall. Their spotlights burn hot. Grubby hands peck at me And fling me into wicker baskets Then take me to bustling factories and burn me, Till I am drained of all energy. Gone, the dark mines, My home. But I am cooled now, Crowned, Then packaged off to warm houses And in the end they stab me into turkey And so rudely call me a ‘fork’! Eloise, aged 10 (SATIPS Poetry Competition 2011, Highly Commended) In The Cupboard It is dusty here. I would sneeze here. If I could. It is dark here. I would squint here. If I could. It is cold here. I would shiver here. If I could. I was once worn. Long ago. I would wear myself. If I could. Sophie, aged 10 Winter Tree The sky is pale, unforgiving Sending down a shower of snow To obscure my vision While the world around me slows I hear ribbons of bird song all around me The sky is crying once again As I am left alone to wait Time is dragging a whale behind it The wind curls around my wiry branches Smothering me in a blanket of cold Licking off my leaves Leaving me dying Chloe, aged 11 A Life Journey My arms stretched out in the sunshine, Covered in a pea-green coat, The birds sang tunes in my ear, I was happy. The seasons flew by to winter, And when my leaves were gone, They got an axe and cut my body, Leaving me to fall. They drove me to a factory, Where bright lights blinked. A machine sliced me into sticks. I was scared. Now we lie in small yellow boxes, Our heads a flaming red, Sad and disbelieving, As we wait to be struck Dead Audrey, aged 12 Typewriter If you were to walk through the bramble thicket, Their fierce claws raking, Their dying branches aching For a glint of light, or breath of wind, You would find it. Like a ghost of things that have gone, Cracked, mistreated, Forgotten, cheated. No longer used or known By anyone today. Each faded letter on grimy keys, Layered in age, Yet in it a page Has stayed since the time it was written upon And the typewriter knows. Years have passed since it was common, When people tapped With pleasure rapt And the object knew the writing, Such wonderful knowledge now fading. As it used to be, set on mahogany table, It can wish And cherish Anna, aged 12 (SATIPS Poetry competition 2012 - Years 5 & 6 Winner) |

AuthorSixteen years of teaching poetry to children have furnished me with a wealth of ideas. Do dip in and adapt any of these for your own lessons. Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed