‘The Sea’ by James Reeves The simplicity of James Reeves’ opening line of ‘The Sea’ is what makes this a particularly useful poem for teaching children about the power of metaphor. The poem almost seems to write itself after this basic premise, with the young reader’s mind already primed and excited to embark on the journey aboard Reeves’ train of thought. Indeed, this is one of the many poems that I have used with which the first 15 minutes of the lesson are often happily and productively spent bouncing around the implications of this initial line: Do you agree? Why? Why not? In what way is the sea a ‘hungry dog’? What does it do? Why does it do it? etc. The questions arise quite naturally and the children - whatever their age - always respond with plenty of creative and original ideas, prior to ever seeing anything other than Reeves’ opening line. Perhaps this comes down in part to its vocabulary, which is accessible to all and therefore linguistically unthreatening. I would argue, however, that the primary reason why this opening line hooks the young poet is that there is an innate openness to metaphor in most, if not all, children. The very use of the metaphorical ‘is’ as opposed to the simile-generating structure ‘is like’ immediately challenges the child to think more deeply and, in doing so, they are quick to tap into the noises, smells, colours and shapes of the sea that make the dog comparison resonate. When they then look at Reeves’ actual lines, children are quick to notice the long, low sounds of the sea echoed in the long vowel sounds - ‘rolls’, ‘hour upon hour’, ‘howls’ - and the irregular but insistent rhyme scheme - ‘bones/stones/moans’, ‘jaws/gnaws/paws/roars/shores/snores, ‘sniffs/cliffs’ - that evokes the varying rhythms of the waves. Assonance, alliteration and onomatopoeia play central roles in conveying the sounds of the sea in this poem and valuable time can be spent not merely in identifying where these are within the poem but what exact effects they are creating. I recall one Year 5 child mentioning that the lines - “And 'Bones, bones, bones, bones! ' The giant sea-dog moans”

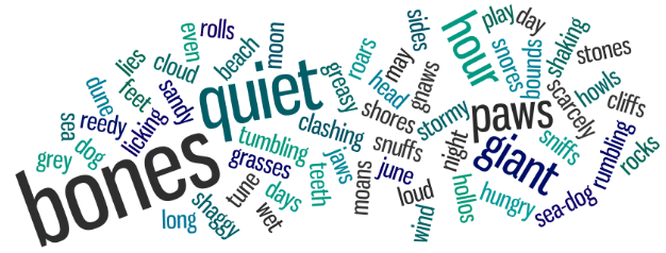

The Forest The forest is a lonely cow Lumbering and brown. She swishes, swishes the sky all night. With her smooth teeth and slow jaws Hour upon hour she chews The echoing, dark trees, And lows, lows, lows, lows! The lumbering forest-cow lows, Standing stock still On her huge tree-trunk legs. And when the morning wind is hollow And the sun sways in the windy day, She stays on her feet and rustles and chews, Shaking her fleas, wanting peace, She groans and moans long and slow. Ingo, aged 10 Much of what makes ‘The Sea’ such a memorable poem comes down to the clever use of repetition and rhyme, so as to provide a constant reminder of the recurrent sounds of the seascape. As Ingo has done in his forest poem, finding ways of conveying the sounds of a place through combinations of onomatopoeia, alliteration and assonance (‘swishes, swishes the sky all night’/’lows, lows, lows, lows’/’She groans and moans long and slow’) really appeals to the child’s innate fascination with words as playthings to be put together rather like Lego bricks to create colourful, crazy structures, as opposed to using them simply to string together units of meaning. Like Reeves, Ingo has ‘built’ his forest metaphor from a montage of interesting sounds and images, allowing him not to get bogged down with literal interpretation. To further facilitate children with tapping into this technique, a very useful app to consider using is www.EdWordle.net Insert any text into it and you can instantly create a ‘word cloud’ of it, in which the more often a word occurs, the larger it will appear. Here is a word cloud of ‘The Sea’ with common words (e.g. ‘the’, ‘and’, ‘but’) removed: Word clouds such as these can be used to introduce a poem, in this case, for example, by asking the children to make suggestions as to what the poem represented by it might be about. The prominence of ‘bones’ and ‘paws’ might well lead the children to identify the dog theme fairly quickly; those who then look more closely to find ‘cliffs’, ‘sandy’ and ‘beach’, for example, will start to ask themselves questions. Is this a poem about a dog running around on a beach, maybe? Already, the images of ‘dog’ and ‘sea’ will be brought together in the child’s mind and everyone can set to work on spotting patterns - rhymes, onomatopoeia, alliterative pairs - still without having to worry about the ‘meaning’ of the text itself. In this way, you will be able to have the children engaged in discussing ideas and playing with words, such that once you start looking at the poem itself, they are ‘warmed up’ and ready to start writing in a similar way: The Dark The dark is a dragon Big and black He roars like a lion With a crunching jaw Fierce face All through the night he watches and waits In his sleepy cave Until in rage he awakes He roars and rumbles And breathes blazing fire Into the dawn of the day Tom, aged 10 Winter The winter is a snarling wolf, Biting the ones who disturb it, Rewarding the one who serve it, With cold refreshing snow. But on a warm winter's day, He cowers as the acidic heat, Burns into his body, Ow, ow, ooow! he cries. But on cold days of December, He crosses his domain, Spreading like ice, Howling, howling all the time. And as the winter ends, His eyes shine with sadness, And he slinks down and down, To places men will never go. Ben, aged 10 The Snow Hippo The hippo is a raging winter. Its teeth are splinters, The snow growing over time, Eventually ‘gone’. It is all mine. The size is overwhelming Swelling with snow. It will pounce only if annoyed, The wind moving it all the time. No void can move it, Only heat can. Hugh, aged 10 A Volcano A volcano is like a hungry cobra Vicious and violent He lies watchful, waiting to strike. Tom, aged 9 The Night The night is a lion’s jaw Shutting like a door slammed loudly. Wham! And you can’t see a thing. The night plays tricks on you Like a lion: Quickly. Jim, aged 10 The Eagle The eagle is pure gold. With his great and glimmering beak He soars over the mountains at midday. At night he sledges down the white snow In a blaze of shining light Like a king on his golden toboggan. William, aged 10 (SATIPS Poetry Competition 2011, Highly Commended) One longstanding favourite activity of mine which was inspired by ‘The Sea’ and which has worked particularly well with children at the younger end of the age range is the ‘randomizer’ method of metaphor/simile building. For this, I use tactile objects such as ping-pong balls, which help to make the activity seem like more of a ‘game’ than a ‘lesson’ in the traditional sense. The children simply take a ball from each of three boxes. The thirty or so balls in the first box have random concrete and abstract nouns in the singular form written on them, e.g. ‘rain’, ‘joy’, ‘life’, ‘summer’ etc. The five or six balls in the middle box have either ‘is’ or ‘is like’ written on them. In the third box, there are again thirty or so nouns, often together with a modifier, as per what will work grammatically, e.g. ‘a hurricane’, ‘the ocean’, ‘my bedroom’, ‘candyfloss’. By selecting their three balls at random, the children are given a ready-made simile or metaphor to use as a starting point and to develop in their own way. Often their selection will not make immediate sense and there will often be fits of laughter and protests along the lines of: “Rain is like my bedroom! That’s just silly!” However, with a little encouragement not to reject their selection in favour of a new one, but rather to take the idea away and play with it in rough for a few minutes, there can often be some astonishing results: Happiness My happiness is a child Rushing home to tea Sorrow My sorrow is rain Falling steadily in the night Fear My fear is a sprawling spider Creeping silently behind the enemy Prepared to pounce Breath held Fangs exposed The venom seeps into the withered veins Ollie, aged 9 What is the Sun? The sun is a giant Yorkshire pudding Served piping hot It is a glinting pendulum Dazzling our eyes The sun is a fishing hook Lowered down and down Then hauled back up again But it never catches anything The sun is a large luminous eye Watching over the universe It is a discus Flung from the depths of the deep black sky Benedict, aged 9 What is a River? The river is a blue fist Pounding through the mountains It is a whipping rope Lashing out to sea The river is a deadly blade Slashing countries in half It is a dying man’s lifesaver Glistening in the sun Henry, aged 9 Similes Love is like an avalanche, It builds for years and falls in minutes. Boredom is like a stone, It never changes. Frustration is like the ocean, It shows you knowledge and yet you’re never satisfied. The future is like a candle, But the wick is still to be lit. Joy is like a lighthouse, It shines when needed. Thomas, aged 10 Thoughts A thought is like a story; you never know where it will end. Jealousy is like a flame; it spreads and engulfs your mind. Desire is like ice cream; the more you have the more you want. Frustration is like a star; when it collapses, it sucks you in. The past is a winding road; it spirals around you and makes you who you are. Sebastian, aged 9 (SATIPS Poetry Competition 2013, Years 5 & 6 Winner) Time The future is like ice. You never know when it might break. You might slip and fall, You could stand tall and proud. Beneath the ice hidden secrets could be lurking in the depths. The present is like water. It flows freely and explores. It makes its way through storms of hardship And flows through the clear sky of happiness. The past is like steam. One second it is the water so clear, The next it has turned into thin air, Lost from sight. Emma, aged 10 These poems were written by children across the full ability range, and, as can be seen, each one has its own particular merits in terms of extending the metaphors and similes such that a seemingly inapposite comparison becomes meaningful through deeper exploration. The children were encouraged to really delve into how one randomly selected noun could be compared in some way to another, however difficult that task may seem at first glance. Repeatedly asking themselves how or why X ‘is’ or ‘is like’ Y gave them a model by which to extend their ideas to full effect. By approaching the exercise as a playful philosophical challenge, the writers were all the more driven to come up with original thoughts and, without any need to labour the explanation of metaphors and similes, they got straight to the intended business of creating them for themselves. They were allowed to work on numerous discrete ideas, returning several times to select new ping pong balls; alternatively, as Emma did, they could start with a single comparison (in this case, ‘future’ = ’ice’) and then extrapolate their own equivalents from it (‘present = ‘water’ and ‘past’ = ‘steam’). As I have suggested previously, there is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ way where children’s writing of poetry is concerned; having the flexibility to allow the children to go off in their own direction from a common starting point or towards an agreed goal should always prove successful and pleasurable for all concerned. What particularly interests me about the poems produced by the children engaged in this activity is how clearly one can detect the preferred modus operandi of the child in the finished piece. Those children with more of an impulsive learning style, will tend to be those whose work shows a colourful array of disparate and often unconnected images, which can create startling and exciting juxtapositions. Those children, on the other hand, who like to think through one idea slowly and thoroughly before moving on to another will tend to produce a more measured and coherent composition, going deeper into the underlying meanings. Neither end result is ‘better’ than the other, in my opinion. Indeed, the joy for me as a reader of poems written by children attending the same lesson lies primarily in the often striking differences that emerge between them.

0 Comments

|

AuthorSixteen years of teaching poetry to children have furnished me with a wealth of ideas. Do dip in and adapt any of these for your own lessons. Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed