|

‘Sonnet 18’ by William Shakespeare

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate: Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May, And summer’s lease hath all too short a date; Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines, And often is his gold complexion dimm'd; And every fair from fair sometime declines, By chance or nature’s changing course untrimm'd; But thy eternal summer shall not fade, Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st; Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade, When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st: So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee. I don’t remember exactly when I first heard the words ‘sonnet’ or ‘iambic pentameter’ for the first time, but I do know that it wasn’t until I was well into my secondary education. This is not to condemn any of the teaching that I received, which was, from my memory, filled with joy and fascination at every turn. Indeed, Shakespeare’s ‘Sonnet 18’ is one that I vividly recall encountering in one of my Year 7 English lessons. It was presented to us by reference to its first line - ‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?’ - as is customary and I remember the teacher taking us through, line by line, and asking us to take turns at ‘translating’ as we went. I got the third line - ‘Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May’ - and ummed and aahed my way to a rough approximation of Shakespeare’s meaning, thankfully realising that it couldn’t be anything to do with a tornado cutting a swathe through that farm in Kent owned by that bloke who plays Del Boy out of ‘Only Fools and Horses’, even if that was the first image that popped into my mind. This would be my first moment of realisation as to the ubiquity of Shakespeare’s language in contemporary English and I will always be thankful for this one lesson for tuning me into the universal relevance of Shakespeare. He is indeed everywhere: a living, breathing presence embedded ‘in eternal lines’ within the English language, the sentiment of this very sonnet standing as a prophetic epitaph to his own mortality. Looking back at the pleasure I took from ‘working out’ Shakespeare’s metaphors and discussing his rhymes in this lesson, I can’t quite decide how I feel about not being told anything about the form. Perhaps the lesson wasn’t long enough and we just didn’t get round to it. Perhaps my teacher just thought we didn’t ‘need’ to know about any of that yet. And maybe we didn’t, not in regard to what was going to come up in the Year 7 exam, at least. What I do remember, though, is that when I did eventually - two, maybe three years later - discover what a sonnet is and how iambic pentameter works, I felt like I had somehow missed out in the meantime. Satisfying as it was to have that epiphany - “Oh, right! ‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day’ is a sonnet!” - my underlying feeling was one of: “Why couldn’t I have been told that then?” In my experience of teaching, children respond best to poetry when they are given as full a picture as possible. Teaching poetry with regard only to meaning - but ignoring form as something of lesser importance or as something for ‘another time’ - is a missed opportunity. Where meaning can be elusive and arbitrary to the point of frustration for any and all of us - who hasn’t read a poem and thought: “What on earth is she on about?!” - form, where it is used, has rules which are objectively comprehensible and which can, therefore, provide a scaffold for understanding. Grasp the form and you have a starting point from which to proceed with the trickier task of interpretation. Better still, you have structure upon which to hang your own creative words. As Stephen Fry puts it in ‘The Ode Less Travelled’: ‘Learning metre and form and other such techniques is the equivalent of understanding culinary ingredients, how they are grown, how they are prepared, how they taste, how they combine [...] (W)e should never forget that poetry, like cooking, derives from love, an absolute love for the particularity and grain of ingredients - in our case, words.’ Fry’s comparison of poetry to cookery is particularly apposite in this age of the BBC’s ‘Great British Bake-Off’. Consider for a moment which contestants make it through to the latter stages. Is it the avant-garde experimentalists who ignore the rigour of the recipe book and use their baking as a means of ‘self-expression’, chucking in whatever comes to hand and just seeing what happens? Or is it the grafters who have practised, practised and practised again, developing a full grasp of the science behind the art? As far as cookery is concerned, I sadly fall into the former camp. (Thankfully, I am wise enough not to audition for the Bake-Off, although, were I to do so, it might provide a week of inevitable hilarity.) As for poetry, even if I am rather too lazy and lacking in inspiration to be the equivalent of a Bake-Off finalist, I certainly believe in the need for hard graft and this is what I seek to pass on to the children whom I teach. All of this is something of a roundabout way of saying that, in my opinion, teachers should not be shy of asking children to experiment with forms that have traditionally been regarded as being for ‘older’ learners. The notion that primary school children should be limited to ‘simpler’ short forms such as haikus and limericks ignores the fact that, arguably, such forms can be considered harder to reproduce successfully than supposedly trickier ones like the sonnet. Short is not necessarily simple. What’s more, being given an introduction to the form of the sonnet - its fourteen lines divided into octet and sestet (Petrarchan) or three quatrains and a couplet (Shakespearean); its rhyme and metre - does not necessitate the need for children to then write full sonnets in response. Valuable time can be spent using a poem such as ‘Sonnet 18’ merely as a model for single lines of iambic pentameter, couplets or poems in blank verse. Whilst I always spend a little time explaining the rules of strict iambic pentameter, whereby the strong beats should fall on the even-numbered syllables, I also make sure that we explore Shakespeare’s own lines to find examples of his breaking the rules. The children are quick to spot these variations, particularly if we directly compare a purely iambic line such as - And summer's lease hath all too short a date - with the more ambiguous scansion of - Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow'st - which arguably works better if rendered as follows: Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow'st To take another example, we might chat for a while about which of the following we prefer: Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade The different shades of meaning afforded by varying the stress are easily conveyed through repeated reading aloud, both by the teacher and the children, who themselves will often spot a new way of placing the stress to create yet another possible meaning. As Fred Sedgwick has noted: ‘It is certainly more effective to teach this [iambic pentameter] by saying the Shakespeare lines aloud with feeling and sensitivity to the meaning several times, thus allowing the iambic beat to sink into the brain, than to count drably: “te-tum te-tum te-tum te-tum te-tum”.’ With this particular example, I have found few children who favour the first properly iambic rendering, almost all of them preferring, together with Shakespeare, to ‘break the rules’ and tune into more natural speech rhythms. Thus, when getting down to the task of writing, whilst they might initially enjoy the simplicity of putting their strong beats in all the right places, tapping out their ‘te-tum te-tum te-tum te-tum te-tum’ with fingers on the desk as they go, it is never long before they gain in confidence enough to throw off the shackles and let the metre go where it chooses, as seen in these extracts: The Sun The sun setting over the luscious plains, Green as a grasshopper’s delicate wing... Alex, aged 13 Bird The gentle bird, peeking into the room, Wishing for itself, longs for that beauty Which he cannot have, and can only view, But for a moment, he can imagine. Patrick, aged 12 When reading back children’s attempts to ‘write like Shakespeare’, I am always struck by their chance discoveries of other metrical feet, without ever having them explained in advance. The dactyl (‘TUM-te-te’), for example, often crops up, as in these lines: ‘Green as a grasshopper’s delicate wing…’ ‘Cover the garden you planted with me’ When I spot these, I will always pause to comment on them and invite discussion from the class. I might compare them with other lines from other writers that spring to mind which echo their discovery, for example: ‘Woman much missed, how you call to me, call to me’ (‘The Voice’ by Thomas Hardy) Sometimes, the child whose line is rendered in dactyls like these will worry that this means that they have ‘gone wrong’ because there are only four strong beats, not five. This will then lead us into further discussion of Shakespeare himself and whether or not he worried about always having his iambs in a row. We might, for example, take the first line of Sonnet 18 and ask whether we really think that it sounds best with five distinct strong beats - Shall I compare thee to a summer's day? Shall I compare thee to a summer's day? Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day? Metrical purists would, of course, have strong opinions on this question and, being no expert myself, I have no doubt that I have already committed a dreadful faux-pas in even venturing onto this hallowed territory. However, where teaching children to write poetry is concerned, to my mind, we do not want to pass on the message that metre and form are straitjackets from which the writer should not even try to struggle free. Rather, in the school context at least, they are useful tools with which to model ways of writing in verse that are easy and fun to ‘get into’ and which tune the writer’s brain into the possibility and necessity of reading aloud, revisiting, redrafting and, above all, experimenting. Given the freedom to enter into a proper dialogue with Shakespeare, and to regard what can seem at first to be ‘rules’ as merely helpful guidelines, children are capable of rising to the challenge and using Shakespeare as a means to expressing their own ideas: Sonnet Shall I compare life to a fleeting dream? They both become changeless memories Although in the past you can change their stream From peaceful joy to fear and tragedy The path is decided by you, you alone Anything, everything could happen to you Life could be a battle you face on your own Or are we being controlled, if so by whom Somehow somewhere they must come to an end Like trees starved of sunlight with falling leaves Or a shattered plate you cannot mend They are so similar it’s hard to believe Shall I compare life to a fleeting dream? Blankets of time with delicate seams. Amy, aged 12

0 Comments

‘Don’t Cry, Darling, It’s Blood All Right’ by Ogden Nash

By way of experimentation, I decided to use another Ogden Nash poem the following day with a group of gifted and talented Year 8 pupils. It is easy to slip into the mindset that playing with rhyme is more of an activity for the ‘little ones’ and that, by the time young people’s literacy and range of vocabulary is getting on for adult level, poetry writing time is spent more productively on, say, developing original metaphors. I am certainly guilty of such assumptions and I often think twice about using poems where rhyme is the stand-out feature, for fear that it will block the writer’s way to expressing what they truly wish to convey. However, give them a poem that uses rhyme in a way that they are unlikely to have encountered before and children are instantly intrigued and keen to delve in. They willingly abandon the misconception that the priority of their writing is that it must ‘mean’ something and instead, as the 4-year-olds did above, let the rhyme shape the narrative. The beauty of using a poet like Nash for rhyme experiments lies not only in his ubiquitous use of rhyming couplets, in which invented words and deliberately ‘wrenched’ rhymes, for example ‘porpoises/corpoises’, are used for comic effect. There is also the equally intentional disregard for metre: as soon as he reaches the word that makes his line rhyme with its predecessor, that is where the line ends, no matter how long or short it is. I chose ‘Don’t Cry Darling, It’s Blood All Right’ to introduce to my Year 8s because I thought that the theme would be something that they would identify with, but open any anthology of Nash’s poetry and you will find that pretty much any his works can be used to inspire a fun rhyming activity. Simply removing the final words from each line and doing a drag and drop activity on the interactive whiteboard is how we got going, reciting each line as we went and then calling out suggestions for the missing word. Such is the narrative clarity of Nash’s poetry, that the missing word seems to just spring into the listener’s mind automatically. Here is another couplet of his, this time from ‘The Adventures of Isabel’: “She showed no rage and she showed no rancor, But she turned the witch into milk and _______.” The fact that the missing ‘word’ is in fact two words (‘drank her’) makes the guessing no less simple. Do the same activity with a couplet like this one from ‘I Do, I Will, I Have’ - “Moreover, just as I am unsure of the difference between flora and fauna and flotsam and jetsam, I am quite sure that marriage is the alliance of two people one of whom never remembers birthdays and the other never _________.”

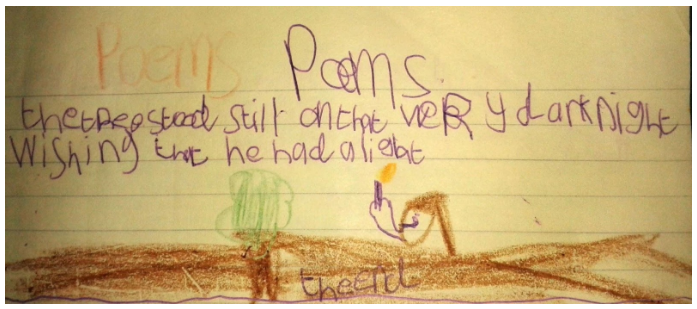

I asked the children what they thought of Nash’s varied line lengths. What did they contribute, if anything, to their enjoyment of the poem? Comments were made to the effect that the ‘wordiness’ made the poem seem more ‘chatty’, that it made the poet seem more ‘real’ to them, because they could tell what he thought about his subject matter. It felt like he was talking to his audience in person and they could get a sense of his humorous and ironic personality. The children also liked the way that his lines seemed to ‘break the rules’, that they hadn’t realised that you could do this kind of thing. This, I found particularly interesting. Somehow, my pupils have developed a sense that poetry has ‘rules’ that must be adhered to, even though they have come across poems of all kinds, written in both fixed forms and free verse. Upon what they supposed the ‘rules’ to be, they could not agree, of course, but something about Ogden Nash’s writing had given them a new sense of the freedom that the poet has to shun what he feels he ought to write and to focus instead upon what and how he wants to write. To give the children an idea of how to get going, I modelled a couplet that came off the top of my head as I wrote it out: “If you ever discover that you’ve lost your pet ostrich, Don’t dismiss the possibility that it’s been kidnapped and taken hostrich (hostage)” Already, as with the animal poems done previously with the 4-year-olds, a narrative has been seeded from the very constraints of the rhyme and it is not hard to imagine how this poem might be continued in the style of one of Nash’s own weird and wonderful tales. All the children needed now was a free rein to share ideas for rhymes out loud and access to an online rhyming dictionary. Within half an hour, they were coming up with their own homages to Nash, like this one, in which Hugo explores his personal fascination with impossibly long words: The Anathema of a Hippopotamonstrosaquippedaliphobic It is necessary to be incredibly stoic, Especially when one is hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliopho’ic, You must be careful when on the telephone, For fear of hearing ‘oxyphenbutazone’, You would much rather end up in a scarier prison Than saying antidisestablishmentarianism, You would certainly love to have itchy nosis If the alternative was suffering from pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis, But this is actually pointless because virtually no one suffers from hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia, So you should probably just ignore it until hell freezes ovia Hugo (aged 13) I enjoyed observing the way in which Hugo systematically worked his way through this poem. He knew that he wanted to find a rhyme for ‘hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobic’ as his starting point and quickly discovered that seemingly his only option that avoided repeating the ‘-phobic’ ending was ‘aerobic’, which didn’t seem to help too much. Undeterred, he experimented with Nash-inspired misspellings - ‘-phobbic’, ‘-phopic’ etc. - before having a go at removing letters. His ‘-pho’ic’ suddenly struck a chord and he immediately had ‘stoic’ in hand to play with and to drive his opening couplet. It was then simply a case of working through the likes of ‘oxyphenbutzone’, ‘antidisestablishmentarianism’ and ‘pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis’ to find suitable rhymes. Wanting to bring the poem full circle with a reappearance of ‘hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia’, he set to mindmapping such promising inventions as ‘globier’, ‘noblier’, ‘robier’ and ‘lobe-ear’ before thinking slightly further outside the box and coming up with the inspired ‘(hell freezes) ovia’, aping Nash’s deliberate misspellings in style. Needless to say, Hugo’s poem, along with several others, way surpassed my expectations at the start of the lesson, which I had envisaged merely as a bit of light relief following a typically joyless examination period, a chance to play with the linguistic Lego bricks before dipping back into the curriculum. If anything, it goes to show that, with poetry at least, when the challenge is there but the pressure is off, children can rise to the occasion and produce more lively and exciting poetry than they might otherwise do in more of a ‘formal’ lesson context. One of the bibles of children’s poetry teaching, Sally Brownjohn’s Does It Have To Rhyme? (Hodder Education, 1980) appeared around the same time as what must be my very first five-year-old dabblings in poetry. I know this because my Kermit the Frog exercise book has miraculously survived to this day and inside, on the pages following a description of my first trip to the cinema to see Superman II, there are a series of illustrated poems, the felt-tip and crayon still vivid as when they were scrawled 34 years ago. Here are some selected highlights:

The butterfly fluttered round the room Zoom zoom zoom The horse went out to play The monkey went out to play They met in the park that very hot day A tree grew golden rings They kept knocking together and going pings The tree stood still on that very dark night Wishing that he had a light In his introduction to This Poem Doesn’t Rhyme, editor Gerard Benson makes the following very salient point: "When I’ve talked to children, I’ve found that lots of them think that poetry must [writer’s italics] rhyme, above all else. It often spoils what they write." This is undeniably true and, looking at my own poems as a five-year-old, I can see myself thinking at that time that poetry equals rhyme. Indeed, I would imagine that most children in the early years come across the word ‘rhyme’ (in the context of the phrase ‘nursery rhyme’) significantly prior to the words ‘poem’ and ‘poetry’, so the primacy of rhyme over poetry in the young child’s mind is hardly surprising. On the other hand, if rhyming forms the first meaningful contact with the wider concept of poetry, this is surely no bad thing, provided that the misconception that the two are synonymous with each other is not allowed to persist for too long. Whatever gives children the occasion to get a deeper feel for words and the qualities inherent within them aside from their surface meanings is the first stage on the road to their becoming a writer. Whether or not I wondered as a five-year-old about the need or otherwise for rhyme in poetry, when I look at these writings now, I can see the joy in them, the sense of achievement in making words fit together. Which child does not smile with satisfaction and pride when they complete a jigsaw puzzle or manage to add the last wooden brick to a structure that still somehow remains standing? The same principle surely applies when children play with words. So whilst I would agree wholeheartedly with idea that poetry does not have to rhyme, I would argue that playing with rhyme and other poetic forms that constrain the writer in some way can, paradoxically, be both gratifying and liberating. As Stephen Fry puts it in The Ode Less Travelled: "Rhyme, as children quickly realise, provides a special kind of satisfaction. It can make us feel, for the space of a poem, that the world is less contingent, less random, more connected, link by link." ‘The Duck’ by Ogden Nash I was recently asked by pre-school teachers at St John’s to come and work with their four-year-olds on the theme of farm animals to complement their visit to Wimpole Hall Farm in Cambridgeshire. I would be the first to admit that I find the prospect of doing poetry with children this young somewhat daunting, if only for the fact that I rarely work with children of this age and can get rather hung up with the worry that they might not ‘get’ what I’m on about. Such worries usually end up being unfounded and, aside from the great fun that we have playing with words, I am always amazed by the sophistication with which they can wield them within the context of poetic dialogue. Most notably, by the age of four, children are already comfortable with the concept and the possibilities of rhyme. I chose Ogden Nash’s ‘The Duck’ as the inspiration for the lesson, putting together a simple interactive whiteboard presentation with images of ducks juxtaposed with the poem split into its rhyming couplets. We recited the poem in ‘repeat after me’ fashion, then all together. We paused to discuss the unfamiliar words, with me providing actions for ‘behold’, ‘dines’, ‘sups’ and so on and asking the children to guess at their meanings. We discussed the images that I had used and how they related to what the duck was doing. We recited together again. We discussed a little more. We recited once again. All in all, we had spent somewhere between five and ten minutes engaged simply in immersing ourselves in the poem. By now, the children were ready to demonstrate their memory for rhyme. I simply recited each couplet up to but not including its final word. The children spontaneously responded with the correct word. They didn’t need any prompting or actions to assist them. The words were just there, waiting to be enunciated. This simple experiment serves to demonstrate the power of rhyme not only as a means of training up the memory but as a useful first step to developing that ‘feel’ for poetry that children can naturally tap into. I then gave the children my own response to ‘The Duck’: The Pig Behold the pig! He’s far too big He oinks at you He doesn’t moo. He dines on swill With perfect skill. He finds it good To bathe in mud. As I have said elsewhere, teachers don’t need to worry about crafting poems of Wordsworthian skill when writing for teaching purposes. I just rattle my pieces out whilst in the thick of preparing my lessons and try not to over-edit or perfect them. That is something that I want the children to do, if anything. Can a pig be ‘far too big’, for example? One four-year-old didn’t think so, and we managed to go off on an amusing tangent as to whether there are any animals that are the ‘wrong size’. As the teacher, your task is not become the poet, so much as to model the desire to be like a poet and inspire your pupils to do the same. Showing the children that your words are open to criticism and correction will open their minds to the idea that the poetry writing process is very much one of experimentation and learning as you go along. A poem might never be ‘finished’ and that is fine. Being able to change and improve it at any point, if anything, helps to keep it alive. The children enjoyed the rhymes in ‘The Pig’ in a similar way to those in ‘The Duck’ and were able to remember the rhymes and shout them out after a couple of runs through and a few minutes of discussion. They were now ready to make their own rhymes, following the ‘Behold the [x]!’ pattern. Working in groups with their teachers and teaching assistants, they suggested rhymes for the names of various animals placed in front of them on cards. From these stimuli, they then chose their favourite animal and crafted their poems orally, with the adult assistant scribing their ideas. I moved between the groups and recited their ideas back to them from the scribed notes. This then became an opportunity for reflection and revision. I challenged them to think of more interesting synonyms, for example: “Can you think of another word for ‘eating’?” No need, of course, to waste time explaining the reasoning for this type of question to the child. As Stephen Fry suggests, children enjoy making connections and challenging them to think beyond their original idea fires their imagination. It doesn’t take long before ‘eating’ is expanded into a variety of delicious, onomatopoeic options such as ‘slurping’, ‘gulping’, ‘munching’ or ‘crunching’: The Rabbit Behold the rabbit! He has a habit Of crunching on carrots And playing with parrots. Imogen (aged 4) The nonsense element of rhymes such as Imogen’s only serves to enhance the joy of the activity for the child. Never mind the improbability of rabbits frolicking with parrots, the image has embedded itself in the young writer’s mind and she has made it happen. She most likely won’t have spotted the fortuitous assonance of her ‘a’ sounds in each of her final words, or indeed the eye-rhyme, but this, of course, does not matter one bit. What matters is the lesson learnt about what words can be made to do in addition to the simple rendering of meaning. The following three examples show a similar sense of freedom from the restrictions of logic and common sense. Instead of the children coming up with a story in advance and then trying to find rhymes to make the poem ‘work’, they have given their imaginations free rein to let the rhyme itself do the deciding and steer the narrative. The Hen Behold the hen! It has a pen To write a letter What could be better? Melissa (aged 4) The Troll Behold the troll! He fell in a hole Whilst carrying a fridge Over a bridge. Bron (aged 4) The Llama Behold the llama! It ripped its pyjamas And you can see If you look carefully Its big fluffy tail Is white and pale It needs sun lotion To jump in the ocean. Thomas (aged 4) ‘Last Post’ by Carol Ann Duffy

Remembrance can be a tricky theme for teachers to approach with children. Now that we live in a world with no surviving participant in The Great War, the collective memory is entirely second hand. The same will all too soon be true of World War Two, which only adds to the importance of remembrance within the teaching of present and future generations. Teachers face an increasingly daunting task. As remembrance gradually loses its direct link to personal memories and drifts entirely into the realms of history, how do teachers themselves retain enough of an understanding of what we mean by remembrance in order to keep it alive in the minds of their pupils? How do we keep the symbolism of the poppy appropriately linked to its various associations: sacrifice, loss, mourning, suffering, the passage of time, memory, love? How do we prevent the events that Remembrance Day commemorates from fading to the same degree as those of the wars of the more distant past? Fortunately, there is poetry. The poetry of Owen, Brooke, Sassoon, Graves, Edward Thomas, and others who experienced war at first hand, has stood, and will continue to stand, the test of time, providing eternal and salient reminders of why the world should never forget. The works of these poets will always be at the disposal of teachers wishing to enable their pupils to grasp what we mean when we say ‘remembrance’ and to understand why we continue to place importance upon it. In addition, however, there are the poems written by poets of subsequent generations, who, in spite of having no direct personal involvement in conflict, have enabled the genre of war poetry to develop and to remain as relevant as ever. Teachers, and more importantly, children themselves can play an important role in this continued development. It may seem to be rather a big ask to get children to write war poetry. Aside from the obvious difficulties presented by a lack of meaningful context or personal experience, there is the risk that cliche takes over and the end result renders banal that which ought to be at the very least moving and profound. Some might argue that children’s minds are simply not sophisticated enough to deal with the complexities of war, let alone convey anything new or meaningful about it on paper. My own opinion, however, is that children are indeed capable of addressing ‘grown-up’ concepts such as war, provided that they are given a suitable frame of reference. This is why ‘remembrance’ - as opposed to ‘war’ - provides a potentially more useful starting point from which to cover the same ground. Carol Ann Duffy’s 2009 poem ‘Last Post’, for instance, is more of a poem of remembrance than it is a war poem. Written at the request of BBC Radio 4’s Today programme to commemorate the deaths of Harry Patch and Henry Allingham, Britain’s last surviving veterans of the Great War, Duffy’s poem is a response to Wilfred Owen’s ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’. She imagines a soldier-poet, possibly Owen himself, overseeing a magical rewinding of tragic events, bringing about the resurrection of ‘all those thousands dead’ through the power of his words. Of course, such miracles cannot happen: ‘If poetry could truly tell it backwards, then it would.’ This, however, should not stop the poet from trying, from hoping that words might somehow save lives. Here is a message from which children can benefit and a wish to which we can encourage them to aspire. Working with my own Year 7 and 8 pupils, within the context of the World War One centenary commemorations in November 2014, I asked them to emulate Duffy’s example by writing not directly about war, but rather to use war only as a reference point to write about what they thought the word ‘remembrance’ means. Classroom discussions, therefore, focused on questions such as “Are there things which should be forgotten?” or “What are the best ways of remembering?” rather than anything directly alluding to war. War, of course, inevitably came into our conversations, but by opening up the broader connotations of remembrance, the children were able to explore ideas that made sense to them from their own experience, as opposed to ideas acquired second-hand from the media and history books. We compared Duffy’s ‘Last Post’ with other poems of remembrance, such as the following: Gunpowder Plot by Vernon Scannell ‘The Plumber’ by Gillian Clarke ‘MCMXIV’ by Philip Larkin These three poems interest me for their use of settings outside of wartime. In this sense, they are not ‘war’ poems in the usual sense of the word. ‘Gunpowder Plot’ deals with a memory of war reawakened on a subsequent Bonfire Night; ‘The Plumber’ focuses upon Harry Patch’s post-war career; ‘MCMXIV’ reimagines the innocence of Edwardian England in August 1914 at the moment when The Great War was declared. The poets are commenting not so much on war per se, but on human stories that surround it. We are all touched by war, however indirectly it may be, and poetry of remembrance will therefore always serve a purpose. For many children lucky enough to live in countries like the UK, life may pass from day to day without any specific thought given to war and its consequences. The occasional sobering reminder in the form of contact with poems such as these, together with the opportunity to respond, can help to ensure that children remain aware of the mistakes of the past and keep a mindful eye on the present. When planning their poems, the children were asked to brainstorm what the word ‘remembrance’ (or ‘remember’) means to them. I asked them to use whatever means they wished to in order join the dots between the present day as they experience it and the events of the two world wars. Some of them drew family trees and made inquiries at home to find out about their ancestors’ wartime experiences. Others used Google to research the background to certain familiar places, for example, their home village’s war memorial. Certain children were able to bring in treasured artefacts including letters written from the Somme, medals and items of kit brought back from the battlefields. The opportunity to handle and discuss authentic pieces of history added a gravitas to the process. I asked them to consider the journey of the objects that they were looking at. How, where, when and why were they originally created? Where have they been over the intervening years? How did they make it here today, to a classroom in Cambridge in 2014? All of this preparatory work was intended to make sure that the children felt a tangible link between the past and the present. Rather than thinking that remembrance is solely a question of recalling historical events, they needed to get a feel for the complex web that connects those events to each and every one of us in the here and now. Once they began writing, I was pleased to see how the children were as conscious of the present as they were of the past. They wanted to explore stories from their own families and their own experience, rather than attempting to write poems around entirely imagined historical scenarios. The end results are moving for their simplicity and believability. 1895-1987 I understand it all now The gun you said was an air rifle The cap badge you said you’d picked up In the old antique shop with your friend who walked with on one leg You weren’t a tin miner Who lost his arm when a boulder fell on it - at least not all your life I understand the musty tin that put tears in your eyes That you’d never open, with a queer picture of some monarch on Why you always piled your savings into The tin of the Help for Heroes lady And why you always closed your eyes for a moment When I got out my tin soldiers You never talked about the war But I realised when finally I saw the identification card Proctor, James - A7004915 B.E.F Lancashire Fusiliers and a picture of a dashing young man in suit and tie He knows I know, so I always lay a poppy at his tomb As he lies in the frozen grave in Houghton, England The line on the old stone grave reads: He who fought with God, rests in peace. Rupert, aged 13 Great-Great Uncle Charlie I never met you, but I heard stories. Not very often, but still sometimes They said that you died very quickly, In the first week of WW1. I wish I knew more about you. I picture you wearing an old-fashioned hunting jacket, Holding a great shiny gun, perhaps with a dog or two, A man with dark hair and a strong jaw, like my brother. They named him after you. My big brother Charles, but they call him Charlie like you, Once Granny said he was just like you. She was your niece. They said you weren’t very brave or good at fighting, but I don’t care. I think that you were brave. I will remember you. You with your poppy. Chiara, aged 12 Remembrance In school we’re always told to remember things: Complicated equations Correct grammar Religious laws Geographical locations Irregular verbs Perfect tenses And ‘important dates and mistakes’. But Grandpa was in a war, and he doesn’t want to remember that He tells us that we shouldn’t need to know. He always talks about before the war, He always talks about after the war, But he never speaks about the war itself. He lost his friends, His cousins, His brothers, His mother, His father, His spirit. That’s what Grandma said. George, aged 13 |

AuthorSixteen years of teaching poetry to children have furnished me with a wealth of ideas. Do dip in and adapt any of these for your own lessons. Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed