|

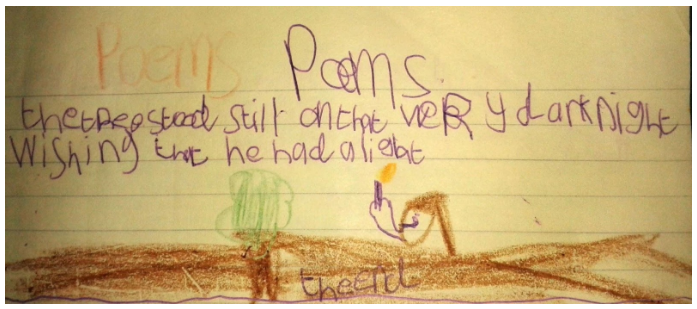

One of the bibles of children’s poetry teaching, Sally Brownjohn’s Does It Have To Rhyme? (Hodder Education, 1980) appeared around the same time as what must be my very first five-year-old dabblings in poetry. I know this because my Kermit the Frog exercise book has miraculously survived to this day and inside, on the pages following a description of my first trip to the cinema to see Superman II, there are a series of illustrated poems, the felt-tip and crayon still vivid as when they were scrawled 34 years ago. Here are some selected highlights:

The butterfly fluttered round the room Zoom zoom zoom The horse went out to play The monkey went out to play They met in the park that very hot day A tree grew golden rings They kept knocking together and going pings The tree stood still on that very dark night Wishing that he had a light In his introduction to This Poem Doesn’t Rhyme, editor Gerard Benson makes the following very salient point: "When I’ve talked to children, I’ve found that lots of them think that poetry must [writer’s italics] rhyme, above all else. It often spoils what they write." This is undeniably true and, looking at my own poems as a five-year-old, I can see myself thinking at that time that poetry equals rhyme. Indeed, I would imagine that most children in the early years come across the word ‘rhyme’ (in the context of the phrase ‘nursery rhyme’) significantly prior to the words ‘poem’ and ‘poetry’, so the primacy of rhyme over poetry in the young child’s mind is hardly surprising. On the other hand, if rhyming forms the first meaningful contact with the wider concept of poetry, this is surely no bad thing, provided that the misconception that the two are synonymous with each other is not allowed to persist for too long. Whatever gives children the occasion to get a deeper feel for words and the qualities inherent within them aside from their surface meanings is the first stage on the road to their becoming a writer. Whether or not I wondered as a five-year-old about the need or otherwise for rhyme in poetry, when I look at these writings now, I can see the joy in them, the sense of achievement in making words fit together. Which child does not smile with satisfaction and pride when they complete a jigsaw puzzle or manage to add the last wooden brick to a structure that still somehow remains standing? The same principle surely applies when children play with words. So whilst I would agree wholeheartedly with idea that poetry does not have to rhyme, I would argue that playing with rhyme and other poetic forms that constrain the writer in some way can, paradoxically, be both gratifying and liberating. As Stephen Fry puts it in The Ode Less Travelled: "Rhyme, as children quickly realise, provides a special kind of satisfaction. It can make us feel, for the space of a poem, that the world is less contingent, less random, more connected, link by link." ‘The Duck’ by Ogden Nash I was recently asked by pre-school teachers at St John’s to come and work with their four-year-olds on the theme of farm animals to complement their visit to Wimpole Hall Farm in Cambridgeshire. I would be the first to admit that I find the prospect of doing poetry with children this young somewhat daunting, if only for the fact that I rarely work with children of this age and can get rather hung up with the worry that they might not ‘get’ what I’m on about. Such worries usually end up being unfounded and, aside from the great fun that we have playing with words, I am always amazed by the sophistication with which they can wield them within the context of poetic dialogue. Most notably, by the age of four, children are already comfortable with the concept and the possibilities of rhyme. I chose Ogden Nash’s ‘The Duck’ as the inspiration for the lesson, putting together a simple interactive whiteboard presentation with images of ducks juxtaposed with the poem split into its rhyming couplets. We recited the poem in ‘repeat after me’ fashion, then all together. We paused to discuss the unfamiliar words, with me providing actions for ‘behold’, ‘dines’, ‘sups’ and so on and asking the children to guess at their meanings. We discussed the images that I had used and how they related to what the duck was doing. We recited together again. We discussed a little more. We recited once again. All in all, we had spent somewhere between five and ten minutes engaged simply in immersing ourselves in the poem. By now, the children were ready to demonstrate their memory for rhyme. I simply recited each couplet up to but not including its final word. The children spontaneously responded with the correct word. They didn’t need any prompting or actions to assist them. The words were just there, waiting to be enunciated. This simple experiment serves to demonstrate the power of rhyme not only as a means of training up the memory but as a useful first step to developing that ‘feel’ for poetry that children can naturally tap into. I then gave the children my own response to ‘The Duck’: The Pig Behold the pig! He’s far too big He oinks at you He doesn’t moo. He dines on swill With perfect skill. He finds it good To bathe in mud. As I have said elsewhere, teachers don’t need to worry about crafting poems of Wordsworthian skill when writing for teaching purposes. I just rattle my pieces out whilst in the thick of preparing my lessons and try not to over-edit or perfect them. That is something that I want the children to do, if anything. Can a pig be ‘far too big’, for example? One four-year-old didn’t think so, and we managed to go off on an amusing tangent as to whether there are any animals that are the ‘wrong size’. As the teacher, your task is not become the poet, so much as to model the desire to be like a poet and inspire your pupils to do the same. Showing the children that your words are open to criticism and correction will open their minds to the idea that the poetry writing process is very much one of experimentation and learning as you go along. A poem might never be ‘finished’ and that is fine. Being able to change and improve it at any point, if anything, helps to keep it alive. The children enjoyed the rhymes in ‘The Pig’ in a similar way to those in ‘The Duck’ and were able to remember the rhymes and shout them out after a couple of runs through and a few minutes of discussion. They were now ready to make their own rhymes, following the ‘Behold the [x]!’ pattern. Working in groups with their teachers and teaching assistants, they suggested rhymes for the names of various animals placed in front of them on cards. From these stimuli, they then chose their favourite animal and crafted their poems orally, with the adult assistant scribing their ideas. I moved between the groups and recited their ideas back to them from the scribed notes. This then became an opportunity for reflection and revision. I challenged them to think of more interesting synonyms, for example: “Can you think of another word for ‘eating’?” No need, of course, to waste time explaining the reasoning for this type of question to the child. As Stephen Fry suggests, children enjoy making connections and challenging them to think beyond their original idea fires their imagination. It doesn’t take long before ‘eating’ is expanded into a variety of delicious, onomatopoeic options such as ‘slurping’, ‘gulping’, ‘munching’ or ‘crunching’: The Rabbit Behold the rabbit! He has a habit Of crunching on carrots And playing with parrots. Imogen (aged 4) The nonsense element of rhymes such as Imogen’s only serves to enhance the joy of the activity for the child. Never mind the improbability of rabbits frolicking with parrots, the image has embedded itself in the young writer’s mind and she has made it happen. She most likely won’t have spotted the fortuitous assonance of her ‘a’ sounds in each of her final words, or indeed the eye-rhyme, but this, of course, does not matter one bit. What matters is the lesson learnt about what words can be made to do in addition to the simple rendering of meaning. The following three examples show a similar sense of freedom from the restrictions of logic and common sense. Instead of the children coming up with a story in advance and then trying to find rhymes to make the poem ‘work’, they have given their imaginations free rein to let the rhyme itself do the deciding and steer the narrative. The Hen Behold the hen! It has a pen To write a letter What could be better? Melissa (aged 4) The Troll Behold the troll! He fell in a hole Whilst carrying a fridge Over a bridge. Bron (aged 4) The Llama Behold the llama! It ripped its pyjamas And you can see If you look carefully Its big fluffy tail Is white and pale It needs sun lotion To jump in the ocean. Thomas (aged 4)

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSixteen years of teaching poetry to children have furnished me with a wealth of ideas. Do dip in and adapt any of these for your own lessons. Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed