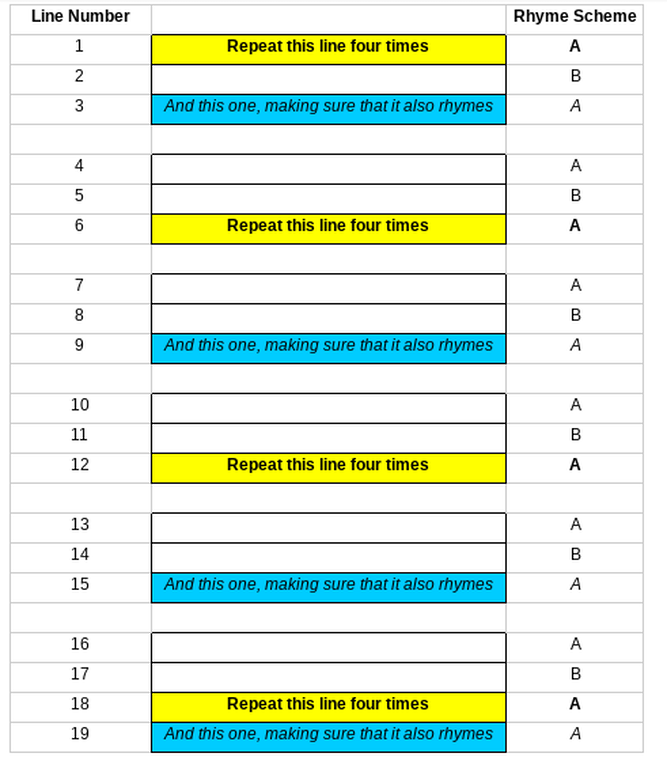

‘Villanelle’ by Sondra Ball Another form of poetry that is traditionally taken to be difficult, and therefore ‘not for children’ is the villanelle. Originating in Italy in the sixteenth century, it is a ‘closed’ form consisting of only two rhymes and repeating lines which follow a fixed pattern. There are five tercets (three-line stanzas) and a final quatrain (four-line stanza). Each tercet follows the rhyme scheme ABA, whilst the quatrain must take an ABAA scheme. Within these limitations, there is the further requirement that specific lines must be exact (or close) repetitions of each other. Lines 1, 6, 12 and 18 match; lines 3, 9, 15 and 19 do likewise. As with the triolet, the easiest way to grasp this pattern is to see it laid out diagrammatically: The lines left blank are all different and must only rhyme as per the given rhyme scheme. There are no fixed rules as to length or metre for any of the lines. When applied this scheme is mapped onto to Sondra Ball’s villanelle, the pattern becomes clear. As a teenager, I first discovered perhaps the best known villanelle in the English language: ‘Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night’ by Dylan Thomas I remember being taken by the haunting nature of the repetition and the power that built up through the course of the poem, the lines carrying more passion and meaning with each repetition. As with the Shakespearean sonnet, I did not know at the time that this poem’s form had a name and a history, assuming that Thomas had devised the structure himself. Only through chance discoveries of other villanelles, such as Elizabeth Bishop’s ‘One Art’ and W H Auden’s ‘If I Could Tell You’, did I recognise the familiar form and make further inquiries. When eventually I came across Ball’s beautifully self-referential ‘Villanelle’ a couple of years ago, I started to wonder about the possibility of using it with children. The first stage with teaching closed forms like this is, for me, always to write one or two of my own, just to be sure that I am not barking up the wrong tree. (Perhaps these villanelles really are as difficult as they are cracked up to be, so letting children loose on them could well prove to be torture for all concerned... ) However, the beauty of having a go at a poem in a closed form is that you at least know before you get going as to what you are trying to do and how your end result should end up. To revisit my previous cookery analogy, having a kitchen full of ingredients and no idea as to what you are trying to make is going to be a hit-and-miss affair at best. Knowing that you are trying to make a Coffee and Walnut cake, on the other hand, at least tells you that the tabasco sauce, the anchovies and the Oxo cubes needn’t be even taken out of the cupboard, let alone experimented with. Here’s what I came up with after half an hour or so of messing about: Villanelle The clock’s slow ticks. Your heart’s dry beat. The telephone waits, indifferently dumb, And endlessly the days and nights repeat. Footsteps thump from the frozen street, Fade to air like a passing drum. “The clock’s slow,” ticks your heart’s dry beat. The fire gives off an unfelt heat, The radio, a half-heard hum, And endlessly the days and nights repeat. One by one your hopes retreat, As shadows on the floor become The clock’s slow tick, your heart’s dry beat. Pages snowdrift at your feet. You stare them through, unreading, numb, And endlessly. The days and nights repeat Until their sameness is complete And now you know I will not come. The clocks, slow, tick your heart’s dry beat And, endlessly, the days and nights. (Repeat.) Ashley Smith The previous week I had been looking at Wilfred Owen’s ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ with my Year 8s as part of our studies of Remembrance Day. I think this is how the idea of the woman gripped by the agony of waiting for news of a loved one first emerged. It is interesting, however, that I did not consciously set out to use that particular idea. Instead, I simply started with the image of a clock and tried to turn that into a line that had the flexibility to have different meanings, in spite of needing to be repeated four times: The clock’s slow ticks. Your heart’s dry beat. “The clock’s slow,” ticks your heart’s dry beat. The clock’s slow tick, your heart’s dry beat. The clocks, slow, tick your heart’s dry beat As well as being enjoyable to generate, this kind of word play has obvious value in the teaching of parts of speech, syntax, grammar and punctuation, and, having designed this to be a ‘teaching’ poem, I was pleased to see how responsive the children were to the nuances of meaning offered by, for example, the presence or absence of an apostrophe: the clocks (plural noun); the clock’s (‘the clock is...’); the clock’s (‘of the clock’). They were also quick to spot how the heart is personified by the introduction of speech marks - “The clock’s slow,” ticks your heart’s dry beat. - and had some lively discussion as the difference in effect between the full stop and the comma working as caesuras in the otherwise identical lines: The clock’s slow ticks. Your heart’s dry beat. The clock’s slow tick, your heart’s dry beat. Some felt that there was no tangible difference. Others thought that the full stop in the middle of the very first line makes the woman seem calm and patient early on, with the later use of the comma suggesting a mind become more agitated and frantic, increasingly driven mad by the clock. These were observations which had not occurred to me whilst writing the poem; I had merely wanted to experiment with using different punctuation as a writer, rather than analyse it with the mind of a close reader. One child suggested that ‘tick’ in the final couplet could be read in the sense of ‘mark’ (i.e. ‘tick off’) as opposed to the sound sense used elsewhere. This, again, hadn’t crossed my mind in the writing process, but I now find that I agree with him and it helps to salvage an otherwise rather clumsy ending. By discussing the process of writing my own villanelle with the children, I was able to develop a greater understanding of the best way to go about it. Whereas I had started with my first line and worked on from there, in fact, it would have been a whole lot easier and more logical to start with the final couplet and work backwards. The final couplet, in that it contains both of the repeating refrains and in that it needs to make sense when the two refrains are juxtaposed, is the key to making the whole poem hang together properly. Daniel, aged 13, clearly understood this and spent more time grappling with his final couplet - Over the sheer cliffs the black bird flies, Under the stormy skies the murky water lies. - than he did with the remainder of his poem, which fell into place for him quite easily when he used a rhyming dictionary to whittle down his two rhymes to a bank of usable words. With these at his disposal, all he then needed to do was to map them onto his ‘villanelle grid’ and use them to anchor the narrative of his poem. The end result is certainly intriguing and shows the curious power of the villanelle to get children writing with haunting potency. Villanelle Over the sheer cliffs the black bird flies, Searching for a place to land Under the stormy skies. The murky water lies Under the cliffs as the black bird tries To find a home on the sand. Over the sheer cliffs the black bird flies. From far away you can hear its cries, You can look towards the sea so bland, Under the stormy skies the murky water lies. Endlessly the ocean will rise, But never will that bird lose heart and Over the sheer cliffs the black bird flies. Although this bird has never been seen by eyes, School children are still told the legend: "Under the stormy skies the murky water lies." So ever if you stand under these skies, Remember my command: "Over the sheer cliffs the black bird flies, Under the stormy skies the murky water lies." Daniel, aged 13

0 Comments

‘Sonnet 18’ by William Shakespeare

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate: Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May, And summer’s lease hath all too short a date; Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines, And often is his gold complexion dimm'd; And every fair from fair sometime declines, By chance or nature’s changing course untrimm'd; But thy eternal summer shall not fade, Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st; Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade, When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st: So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee. I don’t remember exactly when I first heard the words ‘sonnet’ or ‘iambic pentameter’ for the first time, but I do know that it wasn’t until I was well into my secondary education. This is not to condemn any of the teaching that I received, which was, from my memory, filled with joy and fascination at every turn. Indeed, Shakespeare’s ‘Sonnet 18’ is one that I vividly recall encountering in one of my Year 7 English lessons. It was presented to us by reference to its first line - ‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?’ - as is customary and I remember the teacher taking us through, line by line, and asking us to take turns at ‘translating’ as we went. I got the third line - ‘Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May’ - and ummed and aahed my way to a rough approximation of Shakespeare’s meaning, thankfully realising that it couldn’t be anything to do with a tornado cutting a swathe through that farm in Kent owned by that bloke who plays Del Boy out of ‘Only Fools and Horses’, even if that was the first image that popped into my mind. This would be my first moment of realisation as to the ubiquity of Shakespeare’s language in contemporary English and I will always be thankful for this one lesson for tuning me into the universal relevance of Shakespeare. He is indeed everywhere: a living, breathing presence embedded ‘in eternal lines’ within the English language, the sentiment of this very sonnet standing as a prophetic epitaph to his own mortality. Looking back at the pleasure I took from ‘working out’ Shakespeare’s metaphors and discussing his rhymes in this lesson, I can’t quite decide how I feel about not being told anything about the form. Perhaps the lesson wasn’t long enough and we just didn’t get round to it. Perhaps my teacher just thought we didn’t ‘need’ to know about any of that yet. And maybe we didn’t, not in regard to what was going to come up in the Year 7 exam, at least. What I do remember, though, is that when I did eventually - two, maybe three years later - discover what a sonnet is and how iambic pentameter works, I felt like I had somehow missed out in the meantime. Satisfying as it was to have that epiphany - “Oh, right! ‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day’ is a sonnet!” - my underlying feeling was one of: “Why couldn’t I have been told that then?” In my experience of teaching, children respond best to poetry when they are given as full a picture as possible. Teaching poetry with regard only to meaning - but ignoring form as something of lesser importance or as something for ‘another time’ - is a missed opportunity. Where meaning can be elusive and arbitrary to the point of frustration for any and all of us - who hasn’t read a poem and thought: “What on earth is she on about?!” - form, where it is used, has rules which are objectively comprehensible and which can, therefore, provide a scaffold for understanding. Grasp the form and you have a starting point from which to proceed with the trickier task of interpretation. Better still, you have structure upon which to hang your own creative words. As Stephen Fry puts it in ‘The Ode Less Travelled’: ‘Learning metre and form and other such techniques is the equivalent of understanding culinary ingredients, how they are grown, how they are prepared, how they taste, how they combine [...] (W)e should never forget that poetry, like cooking, derives from love, an absolute love for the particularity and grain of ingredients - in our case, words.’ Fry’s comparison of poetry to cookery is particularly apposite in this age of the BBC’s ‘Great British Bake-Off’. Consider for a moment which contestants make it through to the latter stages. Is it the avant-garde experimentalists who ignore the rigour of the recipe book and use their baking as a means of ‘self-expression’, chucking in whatever comes to hand and just seeing what happens? Or is it the grafters who have practised, practised and practised again, developing a full grasp of the science behind the art? As far as cookery is concerned, I sadly fall into the former camp. (Thankfully, I am wise enough not to audition for the Bake-Off, although, were I to do so, it might provide a week of inevitable hilarity.) As for poetry, even if I am rather too lazy and lacking in inspiration to be the equivalent of a Bake-Off finalist, I certainly believe in the need for hard graft and this is what I seek to pass on to the children whom I teach. All of this is something of a roundabout way of saying that, in my opinion, teachers should not be shy of asking children to experiment with forms that have traditionally been regarded as being for ‘older’ learners. The notion that primary school children should be limited to ‘simpler’ short forms such as haikus and limericks ignores the fact that, arguably, such forms can be considered harder to reproduce successfully than supposedly trickier ones like the sonnet. Short is not necessarily simple. What’s more, being given an introduction to the form of the sonnet - its fourteen lines divided into octet and sestet (Petrarchan) or three quatrains and a couplet (Shakespearean); its rhyme and metre - does not necessitate the need for children to then write full sonnets in response. Valuable time can be spent using a poem such as ‘Sonnet 18’ merely as a model for single lines of iambic pentameter, couplets or poems in blank verse. Whilst I always spend a little time explaining the rules of strict iambic pentameter, whereby the strong beats should fall on the even-numbered syllables, I also make sure that we explore Shakespeare’s own lines to find examples of his breaking the rules. The children are quick to spot these variations, particularly if we directly compare a purely iambic line such as - And summer's lease hath all too short a date - with the more ambiguous scansion of - Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow'st - which arguably works better if rendered as follows: Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow'st To take another example, we might chat for a while about which of the following we prefer: Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade The different shades of meaning afforded by varying the stress are easily conveyed through repeated reading aloud, both by the teacher and the children, who themselves will often spot a new way of placing the stress to create yet another possible meaning. As Fred Sedgwick has noted: ‘It is certainly more effective to teach this [iambic pentameter] by saying the Shakespeare lines aloud with feeling and sensitivity to the meaning several times, thus allowing the iambic beat to sink into the brain, than to count drably: “te-tum te-tum te-tum te-tum te-tum”.’ With this particular example, I have found few children who favour the first properly iambic rendering, almost all of them preferring, together with Shakespeare, to ‘break the rules’ and tune into more natural speech rhythms. Thus, when getting down to the task of writing, whilst they might initially enjoy the simplicity of putting their strong beats in all the right places, tapping out their ‘te-tum te-tum te-tum te-tum te-tum’ with fingers on the desk as they go, it is never long before they gain in confidence enough to throw off the shackles and let the metre go where it chooses, as seen in these extracts: The Sun The sun setting over the luscious plains, Green as a grasshopper’s delicate wing... Alex, aged 13 Bird The gentle bird, peeking into the room, Wishing for itself, longs for that beauty Which he cannot have, and can only view, But for a moment, he can imagine. Patrick, aged 12 When reading back children’s attempts to ‘write like Shakespeare’, I am always struck by their chance discoveries of other metrical feet, without ever having them explained in advance. The dactyl (‘TUM-te-te’), for example, often crops up, as in these lines: ‘Green as a grasshopper’s delicate wing…’ ‘Cover the garden you planted with me’ When I spot these, I will always pause to comment on them and invite discussion from the class. I might compare them with other lines from other writers that spring to mind which echo their discovery, for example: ‘Woman much missed, how you call to me, call to me’ (‘The Voice’ by Thomas Hardy) Sometimes, the child whose line is rendered in dactyls like these will worry that this means that they have ‘gone wrong’ because there are only four strong beats, not five. This will then lead us into further discussion of Shakespeare himself and whether or not he worried about always having his iambs in a row. We might, for example, take the first line of Sonnet 18 and ask whether we really think that it sounds best with five distinct strong beats - Shall I compare thee to a summer's day? Shall I compare thee to a summer's day? Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day? Metrical purists would, of course, have strong opinions on this question and, being no expert myself, I have no doubt that I have already committed a dreadful faux-pas in even venturing onto this hallowed territory. However, where teaching children to write poetry is concerned, to my mind, we do not want to pass on the message that metre and form are straitjackets from which the writer should not even try to struggle free. Rather, in the school context at least, they are useful tools with which to model ways of writing in verse that are easy and fun to ‘get into’ and which tune the writer’s brain into the possibility and necessity of reading aloud, revisiting, redrafting and, above all, experimenting. Given the freedom to enter into a proper dialogue with Shakespeare, and to regard what can seem at first to be ‘rules’ as merely helpful guidelines, children are capable of rising to the challenge and using Shakespeare as a means to expressing their own ideas: Sonnet Shall I compare life to a fleeting dream? They both become changeless memories Although in the past you can change their stream From peaceful joy to fear and tragedy The path is decided by you, you alone Anything, everything could happen to you Life could be a battle you face on your own Or are we being controlled, if so by whom Somehow somewhere they must come to an end Like trees starved of sunlight with falling leaves Or a shattered plate you cannot mend They are so similar it’s hard to believe Shall I compare life to a fleeting dream? Blankets of time with delicate seams. Amy, aged 12 |

AuthorSixteen years of teaching poetry to children have furnished me with a wealth of ideas. Do dip in and adapt any of these for your own lessons. Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed