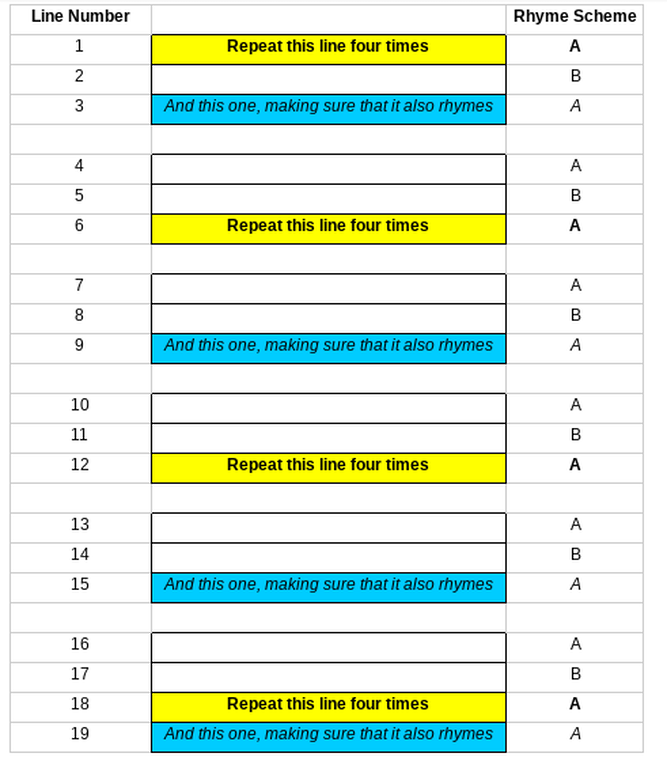

‘Villanelle’ by Sondra Ball Another form of poetry that is traditionally taken to be difficult, and therefore ‘not for children’ is the villanelle. Originating in Italy in the sixteenth century, it is a ‘closed’ form consisting of only two rhymes and repeating lines which follow a fixed pattern. There are five tercets (three-line stanzas) and a final quatrain (four-line stanza). Each tercet follows the rhyme scheme ABA, whilst the quatrain must take an ABAA scheme. Within these limitations, there is the further requirement that specific lines must be exact (or close) repetitions of each other. Lines 1, 6, 12 and 18 match; lines 3, 9, 15 and 19 do likewise. As with the triolet, the easiest way to grasp this pattern is to see it laid out diagrammatically: The lines left blank are all different and must only rhyme as per the given rhyme scheme. There are no fixed rules as to length or metre for any of the lines. When applied this scheme is mapped onto to Sondra Ball’s villanelle, the pattern becomes clear. As a teenager, I first discovered perhaps the best known villanelle in the English language: ‘Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night’ by Dylan Thomas I remember being taken by the haunting nature of the repetition and the power that built up through the course of the poem, the lines carrying more passion and meaning with each repetition. As with the Shakespearean sonnet, I did not know at the time that this poem’s form had a name and a history, assuming that Thomas had devised the structure himself. Only through chance discoveries of other villanelles, such as Elizabeth Bishop’s ‘One Art’ and W H Auden’s ‘If I Could Tell You’, did I recognise the familiar form and make further inquiries. When eventually I came across Ball’s beautifully self-referential ‘Villanelle’ a couple of years ago, I started to wonder about the possibility of using it with children. The first stage with teaching closed forms like this is, for me, always to write one or two of my own, just to be sure that I am not barking up the wrong tree. (Perhaps these villanelles really are as difficult as they are cracked up to be, so letting children loose on them could well prove to be torture for all concerned... ) However, the beauty of having a go at a poem in a closed form is that you at least know before you get going as to what you are trying to do and how your end result should end up. To revisit my previous cookery analogy, having a kitchen full of ingredients and no idea as to what you are trying to make is going to be a hit-and-miss affair at best. Knowing that you are trying to make a Coffee and Walnut cake, on the other hand, at least tells you that the tabasco sauce, the anchovies and the Oxo cubes needn’t be even taken out of the cupboard, let alone experimented with. Here’s what I came up with after half an hour or so of messing about: Villanelle The clock’s slow ticks. Your heart’s dry beat. The telephone waits, indifferently dumb, And endlessly the days and nights repeat. Footsteps thump from the frozen street, Fade to air like a passing drum. “The clock’s slow,” ticks your heart’s dry beat. The fire gives off an unfelt heat, The radio, a half-heard hum, And endlessly the days and nights repeat. One by one your hopes retreat, As shadows on the floor become The clock’s slow tick, your heart’s dry beat. Pages snowdrift at your feet. You stare them through, unreading, numb, And endlessly. The days and nights repeat Until their sameness is complete And now you know I will not come. The clocks, slow, tick your heart’s dry beat And, endlessly, the days and nights. (Repeat.) Ashley Smith The previous week I had been looking at Wilfred Owen’s ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ with my Year 8s as part of our studies of Remembrance Day. I think this is how the idea of the woman gripped by the agony of waiting for news of a loved one first emerged. It is interesting, however, that I did not consciously set out to use that particular idea. Instead, I simply started with the image of a clock and tried to turn that into a line that had the flexibility to have different meanings, in spite of needing to be repeated four times: The clock’s slow ticks. Your heart’s dry beat. “The clock’s slow,” ticks your heart’s dry beat. The clock’s slow tick, your heart’s dry beat. The clocks, slow, tick your heart’s dry beat As well as being enjoyable to generate, this kind of word play has obvious value in the teaching of parts of speech, syntax, grammar and punctuation, and, having designed this to be a ‘teaching’ poem, I was pleased to see how responsive the children were to the nuances of meaning offered by, for example, the presence or absence of an apostrophe: the clocks (plural noun); the clock’s (‘the clock is...’); the clock’s (‘of the clock’). They were also quick to spot how the heart is personified by the introduction of speech marks - “The clock’s slow,” ticks your heart’s dry beat. - and had some lively discussion as the difference in effect between the full stop and the comma working as caesuras in the otherwise identical lines: The clock’s slow ticks. Your heart’s dry beat. The clock’s slow tick, your heart’s dry beat. Some felt that there was no tangible difference. Others thought that the full stop in the middle of the very first line makes the woman seem calm and patient early on, with the later use of the comma suggesting a mind become more agitated and frantic, increasingly driven mad by the clock. These were observations which had not occurred to me whilst writing the poem; I had merely wanted to experiment with using different punctuation as a writer, rather than analyse it with the mind of a close reader. One child suggested that ‘tick’ in the final couplet could be read in the sense of ‘mark’ (i.e. ‘tick off’) as opposed to the sound sense used elsewhere. This, again, hadn’t crossed my mind in the writing process, but I now find that I agree with him and it helps to salvage an otherwise rather clumsy ending. By discussing the process of writing my own villanelle with the children, I was able to develop a greater understanding of the best way to go about it. Whereas I had started with my first line and worked on from there, in fact, it would have been a whole lot easier and more logical to start with the final couplet and work backwards. The final couplet, in that it contains both of the repeating refrains and in that it needs to make sense when the two refrains are juxtaposed, is the key to making the whole poem hang together properly. Daniel, aged 13, clearly understood this and spent more time grappling with his final couplet - Over the sheer cliffs the black bird flies, Under the stormy skies the murky water lies. - than he did with the remainder of his poem, which fell into place for him quite easily when he used a rhyming dictionary to whittle down his two rhymes to a bank of usable words. With these at his disposal, all he then needed to do was to map them onto his ‘villanelle grid’ and use them to anchor the narrative of his poem. The end result is certainly intriguing and shows the curious power of the villanelle to get children writing with haunting potency. Villanelle Over the sheer cliffs the black bird flies, Searching for a place to land Under the stormy skies. The murky water lies Under the cliffs as the black bird tries To find a home on the sand. Over the sheer cliffs the black bird flies. From far away you can hear its cries, You can look towards the sea so bland, Under the stormy skies the murky water lies. Endlessly the ocean will rise, But never will that bird lose heart and Over the sheer cliffs the black bird flies. Although this bird has never been seen by eyes, School children are still told the legend: "Under the stormy skies the murky water lies." So ever if you stand under these skies, Remember my command: "Over the sheer cliffs the black bird flies, Under the stormy skies the murky water lies." Daniel, aged 13

0 Comments

|

AuthorSixteen years of teaching poetry to children have furnished me with a wealth of ideas. Do dip in and adapt any of these for your own lessons. Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed