|

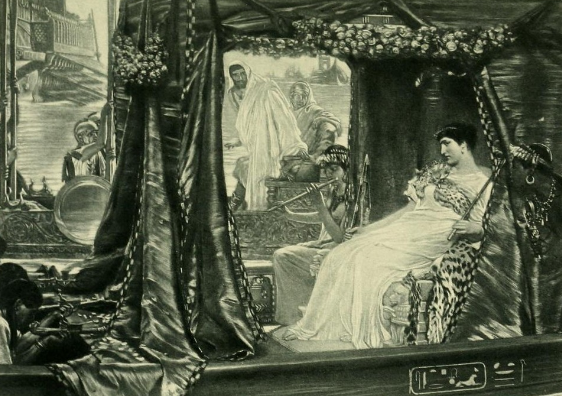

Enobarbus’ Speech from Act II, Scene 2 of ‘Antony and Cleopatra’ by William Shakespeare

The barge she sat in, like a burnished throne, Burned on the water. The poop was beaten gold, Purple the sails, and so perfumèd that The winds were lovesick with them. The oars were silver, Which to the tune of flutes kept stroke, and made The water which they beat to follow faster, As amorous of their strokes. For her own person, It beggared all description: she did lie In her pavilion—cloth-of-gold, of tissue-- O’erpicturing that Venus where we see The fancy outwork nature. On each side her Stood pretty dimpled boys, like smiling Cupids, With divers-colored fans, whose wind did seem To glow the delicate cheeks which they did cool, And what they undid did. [...] Her gentlewomen, like the Nereides, So many mermaids, tended her i' the eyes, And made their bends adornings: at the helm A seeming mermaid steers: the silken tackle Swell with the touches of those flower-soft hands, That yarely frame the office. From the barge A strange invisible perfume hits the sense Of the adjacent wharfs. The city cast Her people out upon her; and Antony, Enthroned i' the market-place, did sit alone, Whistling to the air; which, but for vacancy, Had gone to gaze on Cleopatra too, And made a gap in nature. [...] Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale Her infinite variety: other women cloy The appetites they feed: but she makes hungry Where most she satisfies; for vilest things Become themselves in her: that the holy priests Bless her when she is riggish. When it comes to the question of teaching Shakespeare, there is an unspoken notion that certain plays will ‘work’ with younger children and others are best left for later: GCSE, A-Level and beyond. The ‘Witches’ Song’ from Macbeth, for example, is always an old favourite in the primary schools, alongside scenes from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Tempest and Twelfth Night. However, much as I myself enjoy these particular plays and using them as teaching material, I do not want to feel obliged to stick to tried and tested territory all the time. Overfamiliarity can spoil some of the magic of Shakespeare’s language. Who, after all, has not heard at some point heard children reciting ‘Double, double, toil and trouble...’ as if it were the ninth of ten ‘Hail Mary’s? I certainly remember being one of those children myself once upon a time, knowing the words but not really feeling anything as they came out of my mouth. Dipping into one of the less well known works, however, can yield some interesting results, particularly given that there is less likelihood that the children will have any previous contact with it, formed any preconceptions about it or absorbed it as if by osmosis. Whilst Antony and Cleopatra is a play that would typically not be studied until A-Level, it contains treasures such as Enobarbus’ description of Cleopatra, which can be looked at in isolation with younger children. The hyperbole of the imagery fascinates children, who revel in the idea of winds being ‘love-sick’ with perfume, the waters of the Nile being in love with the silver oars and particles of air wanting to pursue the queen, but for the impossible ‘gap in nature’ that this would cause. I use this speech as the stimulus for writing on the topic of incredible visions. The children are invited to think back to the most beautiful sight they can ever remember seeing and to jot down anything that springs to mind. They add to this any smells, sounds, tastes or textures that were experienced at the time. Finally, they are asked, on another sheet of paper, to imagine this experience being even better. What would be needed to make it even more special? I then leave it to the children to decide whether or not they want to experiment with iambic pentameter and to what extent they want to emulate Shakespearean language. Here are a few brief extracts taken from writing inspired by this activity: The Malvern Hills As I walked along the bare Malvern Hills. A single swallow swung down like a rope. The wind blew cold past my frozen ears, Burning a fiery chill of hopeless hope. Hills spread out before me like a painting. Each brush-stroke shaping wave after wave. The sleek curve fading away in the distance. The Malvern Hills under the sky’s great cave. David, aged 11 The Night Sky Her face sparkling with the glow of stars A billion glowing suns light up her face The sailors love her for she brings them home Even Orion and Sagittarius love her The mighty Scorpio doesn’t dare attack her For she is the mantle of his world... Hugo, aged 11 The Sea Your pebbles unroll like a never-ending story. Your story unravels like a crash of waves Becoming brighter than butterfly wings Than turning windmills and flickering fireflies. Auriel, aged 11 Sea Spray The waves roll across the beach like a page turning Scattering wistful, winding words across the sea. The letters spiral around my feet and spray across the burning sand Luring me to go into the world of words and water. Charlotte, aged 12 Bonfire Night The peaceful night is broken as a splash Of sunlight falls upon its black expanse A phoenix made from lava orb of fire The splashing multi coloured drops of light Some are showers of gold, some emerald green, Some red, some blue, some howling like banshees, The last are silent then shatter the night A lion roars, then fades in milky light The audience watch like statues in gasping awe At the magic they have all just seen As creatures cackle and crackle above their heads Oblivious to them as flames lap at sky Till it fades away and the the silence consumes the night Sam, aged 11 As can be seen in all of these extracts, children are adept at writing about ‘beauty’ in a more abstract way than we might otherwise expect. Rather than restrict themselves to the description of minutiae, they seize upon the opportunity to let their minds wander onto the mysteries of the universe. Their writing seems to ask the question ‘What is Beauty?’ and is content to explore it without trying to pin down definitive answers. To me, it reads as if they are forming a kind of dialogue with themselves through the medium of poetry, a dialogue which need not have a fixed beginning or end, but which can be revisited and reconsidered at any time. The very slowness of the act of writing poetry - whether it be slowed down by the form, by the content or by a combination of both - feeds deeper thinking and, in this sense, poetry and philosophy seem to go hand in hand, particularly where children are concerned. Where much of what they do in the classroom limits opportunities for deep thought and reflection, time being of the essence, poetry only really flourishes when it is allowed to develop at its own pace. As I write, all of the above examples are still very much works in progress, to which the children will, I hope, return at leisure over the coming term, next year and maybe even beyond. There are no deadlines, specific learning targets or boxes to tick. This is writing for the sake of writing and, whether it be in the context of discovering Shakespeare or any other great writer, the results speak for themselves.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSixteen years of teaching poetry to children have furnished me with a wealth of ideas. Do dip in and adapt any of these for your own lessons. Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed