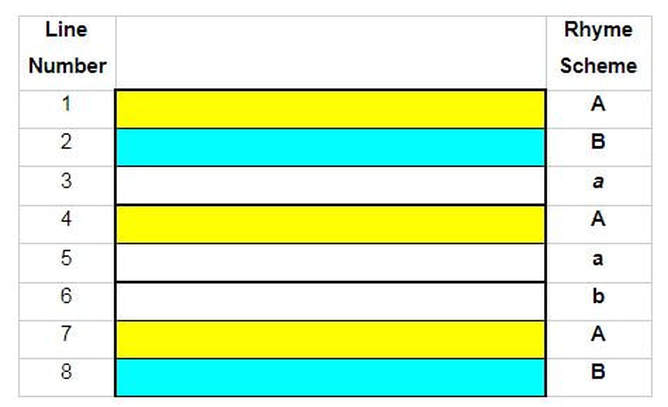

‘Valentine’ by Wendy Cope For as long as I can remember, I have always enjoyed learning about less well known poetic forms. We can all remember coming across limericks, haikus and possibly clerihews at primary school and having a go at creating some of our own. However, there are some other forms out there with just as long and established a tradition which rarely get much of a look in. The triolet, for example, is a form that I have only discovered in recent years, even though it has been around since at least the 14th century and enjoyed a revival in the late 19th century thanks to poets such as Robert Bridges, Frances Cornford and Thomas Hardy. Wendy Cope’s ‘Valentine’ is one of the best known modern triolets, and I have used it successfully alongside other examples to get Year 7 children playing with the form. A triolet is made up of eight lines. It follows an ABaAabAB rhyme scheme, where capitals refer to identical (or near-identical) lines and small letters refer to rhyming lines. Therefore, lines 1, 4 and 7 are identical, as are lines 2 and 8. This also means that the first and final couplets are identical. The lines are often, but not always, written in iambic tetrameter, i.e. with four stresses on the even-numbered syllables. With ‘Valentine’ I start not by giving any information about its form, but by asking the children to discuss the poem in pairs and ask if they can spot anything interesting or unusual about it. They will always spot and comment on the repetition and the rhyme, but, without any point of comparison, they understandably do not see a specific pattern. I then show them the following two poems and ask them to continue discussing: ‘The Puzzled Game-Birds’ by Thomas Hardy They are not those who used to feed us When we were young—they cannot be - These shapes that now bereave and bleed us? They are not those who used to feed us, - For would they not fair terms concede us? - If hearts can house such treachery They are not those who used to feed us When we were young—they cannot be! ‘Triolet’ by Robert Bridges When first we met, we did not guess That Love would prove so hard a master; Of more than common friendliness When first we met we did not guess. Who could foretell the sore distress, This irretrievable disaster, When first we met? -- We did not guess That Love would prove so hard a master. Without any further guidance from me, they are able to come up with an accurate explanation of the triolet form incorporating all of the key features, along the lines of the more technical one given by me above. The satisfaction that comes from ‘cracking the code’ in this way is a real spur for the children in terms of making them want to get stuck in with trying it out for themselves. After all, if they have been able to work out in just a few minutes how a triolet works, the logical next step is to want to put it into practice. Teaching poetry writing in this way neatly sidesteps the age-old problem of coming up with ideas of what to write about and shifts the focus instead to the more technical question of how to go about it. For some children, such an approach can be highly liberating, especially if they can be provided with a literal scaffold upon which to build their writing, like this: I copy this colour-coded grid multiple times onto sheets of paper and let the children try out different lines, making sure that their yellow and blue lines match up. If computers are available, I provide the grid in its original digital spreadsheet format and they can work in a similar way, chopping and changing until they have two refrains that work well in their fixed, repeated positions. I ask them to keep going away and coming back to their ideas repeatedly over several days, even weeks, the beauty of this form being that once you know the pattern, you can just wait for inspiration to come and then the rest will usually fall into place fairly quickly. Here are three triolets produced by the children using this method: Bird Song I can hear them, hear their song. Why can I not answer? Do love birds fly free? For that I long. I can hear them, hear their song. In this cage? Is it true? I can sing along? No, I am the captured dancer. I can hear them, hear their song. Why can I not answer? Sophie, aged 12 Poppies Poppies used to be my favourite flower But now I’ve changed my mind For they grew at daddy’s darkest hour Poppies used to be my favourite flower Now their sweet smell has turned sour For them at the graveyard you will find Poppies used to be my favourite flower But now I’ve changed my mind. Anna, aged 12 Dreams They happen in your head Vivid, colourful and bright Repeating what you could have said They happen in your head You talk to people that are dead Then you wake with an explosion of light They happen in your head Vivid, colourful and bright Isabel, aged 12 I find it interesting that this simple form seems to provide children with quite a lot of fertile ground, in spite of traditionally being regarded as somewhat light and frivolous. Quite why this should be so, I am not too sure, but I would hazard a guess that the ‘serious’ poet might think that eight lines of which one is repeated three times and another is repeated twice gives insufficient elbow room in which to make much of a point. Children, by contrast, are used to being economical with the (written) word, regularly knocking off 500 word stories in forty minutes without blinking. As teachers, we are used to marking stories in which whole lifetimes are lived out in the space of two sides of A4, so the brevity of the triolet is unlikely to faze younger writers. See, for example, this comic gem which might not be wholly out of place amongst Hilaire Belloc’s ‘Cautionary Tales for Children’: Poor Little Wendy There’s a shark swimming in the water And poor little Wendy’s losing her balance Splash! I tried to save her, but it caught ‘er There’s a shark swimming in the water It’s an important lesson it’s taught ’er Even though Wendy had lots of talents There’s a shark swimming in the water And poor little Wendy’s losing her balance. Tom and Sam, aged 11

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSixteen years of teaching poetry to children have furnished me with a wealth of ideas. Do dip in and adapt any of these for your own lessons. Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed